A detailed glimpse at the PIDC industrial land use study

April 15, 2010

By Thomas J. Walsh

For PlanPhilly

NEW ORLEANS – A much-anticipated study due out next month from the Philadelphia Industrial Development Corp. was previewed Monday morning at the American Planning Association conference, held here through Tuesday.

The overview was within the context of a panel discussion titled “21st Century Urban Industrial Strategies.” The idea is that there are opportunities to “refocus” industrial uses that exist now within cities, after decades of pushing industry away. The values of days gone by – easy access to a labor pool, infrastructure that’s already in place, access to vendors and customers, and lower transportation costs – are once again on the front burner at cities’ economic development agencies.

Panelists were Laura Wolf-Powers, assistant professor of city and regional planning at the University of Pennsylvania; Scott Page, principal and founder of Philadelphia-based Interface Studio LLC, which was hired by PIDC for the study; Paul Parkhill, director of planning and development for the Greenpoint Manufacturing and Design Center, a Brooklyn-based nonprofit developer of work space for small manufacturers and artists; and Teresa Lynch, senior vice president at the Initiative for a Competitive Inner City (ICIC) in Boston.

Wolf-Powers

PIDC’s “industrial land use study is part of a trend that has been taking place nationally in a lot of so-called post-industrial cities where economic development professionals and elected officials are taking stock of land use patterns that developed under ancient zoning ordinances,” said Wolf-Powers. “They are figuring out how industrial land use relates to fiscal policy, and to employment policy.”

The Philly study

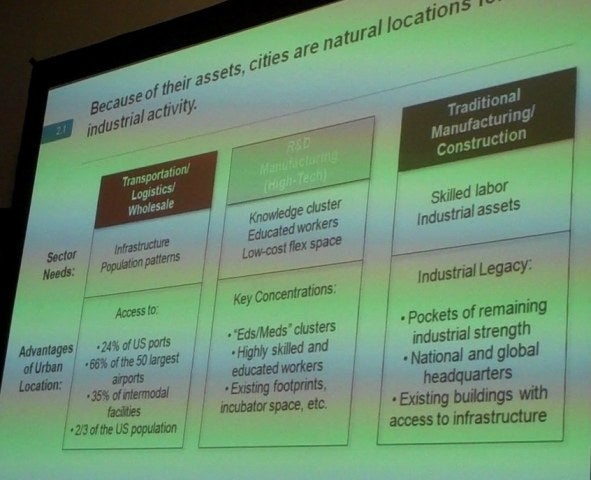

“There’s a growing distribution niche in Philadelphia, in part because we have a couple of ports,” said Page. “There’s a large airport and there’s some great freight rail infrastructure.” There’s also a surprising amount of small-scale manufacturers and wholesalers in the city, especially involved in food processing, he added.

For the forthcoming study, Page said he and some colleagues simply got in a car and started surveying. They covered about 20 percent of the city in 15 different districts – every single property in those districts.

“If we couldn’t tell what was happening from the car, we got out of the car, climbed the fence, sometimes we looked inside of windows we probably shouldn’t have,” he said. “It was an eye-opening experience, because as somebody who has worked in Philadelphia for many years – I’ve done a lot of neighborhood planning, commercial corridor planning – some of these industrial places were completely off the radar for me. And it wasn’t just for me. These are large, forgotten places.”

“We’re trying to do a lot of different things with this,” said John Grady, vice president of real estate services for PIDC, in an interview with PlanPhilly earlier this month. “A lot of it came from, over the past few years, a lot of tension in the real estate market, with industrial zoning, particularly with older industrial districts in the city where the neighborhoods were starting to merge. American Street, parts of Aramingo, Northern Liberties, Callowhill even. And even in more traditional industrial districts, pressure from retail development.

“With the Commerce Department and the Planning Commission, we started to think about our need to rationally evaluate these requests for changes in zoning,” Grady continued. “We needed to have a better sense of where we think the industrial market is today, and where it’s going, in terms of market segments that will present demand. And the type and nature and duration of what the market demands from modern industrial use.”

Clusters of machine-based manufacturing such as the Kensington mill district were actually among the first “industrial suburbs,” Wolf-Powers said. She pointed out the city’s river wards and noted that Philadelphia became a city built on neighborhoods that were clustered around factories with close access to rail lines and the river.

“The development of these industrial proto-suburbs happened before municipal zoning, so the zoning regulation applied to all of this stuff retroactively,” she said, adding that this was also happening at that time when cities grew by large-scale annexation, meaning the manufacturing areas were assimilated in a rather awkward fashion.

Fast-forward to the present day, and “there was so little known about the industrial land in Philadelphia,” said Page. “How is it used? What’s happening on the ground? Philadelphia has a long legacy that we really wanted to get a sense of as part of the study.”

Page said that the PIDC study had two main parts – the economic piece (jobs, revenues, potential markets, etc.) and the land piece. Some cities have ended up doing one or the other very well. It was the goal of this study to combine the two effectively.

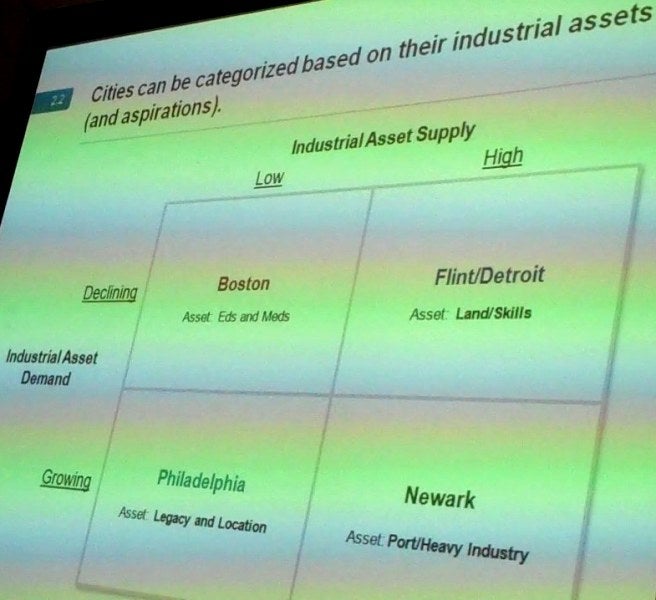

“We’re a very, very diverse industrial city,” Page told the crowd, describing Philly’s past as the “Workshop of the World,” making everything “from bullets to beer to hats.” As such, it did not suffer the swift declines of cities like Detroit, which were not as diverse.

“Despite the decline in manufacturing, Philadelphia’s industrial base has evolved, and the hope of the study is that we can help it evolve a little further,” Page said. “This is a big deal for the city, and it’s something that all of the leadership of city government has really been focused on getting a handle on – what is happening on the industrial land side, and how can we really maximize the value of what we have?”

Philadelphia lost 62 percent of its industrial firms between 1963 and 1992. The phenomenon was not nearly as bad in other parts of the country, but Wolf-Powers points out that those other regions now have similar problems – the competition for prime land between industrial uses and commercial and residential uses.

Wolf-Powers cited the PIDC as being made up of “some pretty forward-thinking leaders” when it was established in 1958 as a joint venture between city government and the Chamber of Commerce. “They made a very deliberate decision to compete with the suburbs, engaging in industrial park development on city-owned land,” she said, referencing her PowerPoint and indicating parks built near the Northeast Philly Airport and to the south at Philadelphia International, and at the Navy Yard.

Industrial does not mean manufacturing

Wolf-Powers said that as more cities undertake industrial land use studies, it is more common for them to consider “the interaction between industrial uses and other uses in supporting the economy as a whole.” At the same time, there is a recognition of the rapid loss of private industrial land to commercial mixed use and residential development, especially in fast–growing municipal areas such as San Francisco, Seattle, San Diego and Washington D.C.

One important underpinning of all the studies is the imperative to get away from the idea that “industrial” is synonymous with “manufacturing.” Trade and exports, information technology and communications, production, distribution and repair (“making, mending or moving things”) are all part of the working industrial lexicon nowadays.

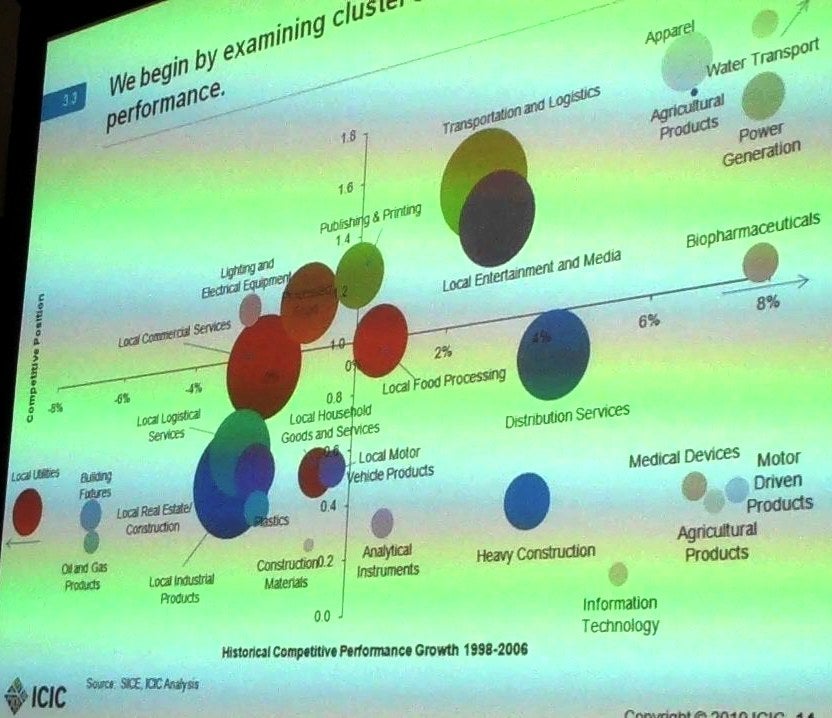

“The number of industrial jobs doesn’t change between 1979 and [projected out to] 2016,” Lynch explained. “But what you see is the composition of industrial jobs goes from two-thirds manufacturing – just standard, traditional manufacturing – and shifts over to two-thirds industrial, meaning things like construction, transportation, logistics. But I think the national discourse has been driven by … a decrease in manufacturing, and there’s been less interest paid to the rest of the industrial sector.”

That’s an important point, because industrial employment has actually remained constant since the late ’70s. What has changed is the mix [in that] manufacturing jobs accounted for 62 percent of industrial employment in 1979; by 2016, it is projected to be only 40 percent. In the meantime, the decline of traditional manufacturing will free up over 1 billion square feet of industrial building space, Lynch said.

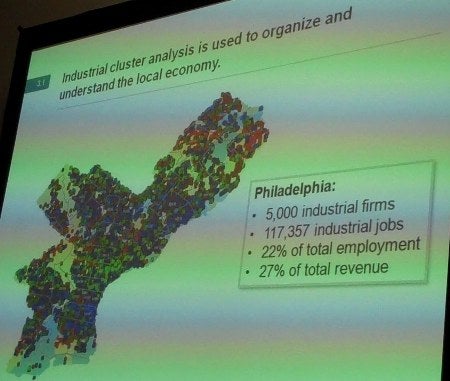

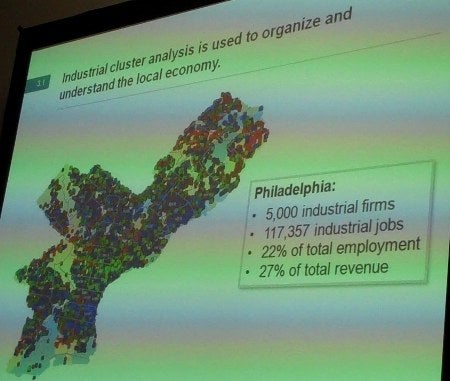

Philadelphia has some 7,691 acres of land considered industrial. It has about 5,000 industrial firms. More than 117,000 industrial jobs constitute 22 percent of the city’s workforce, and 27 percent of Philadelphia’s total revenues.

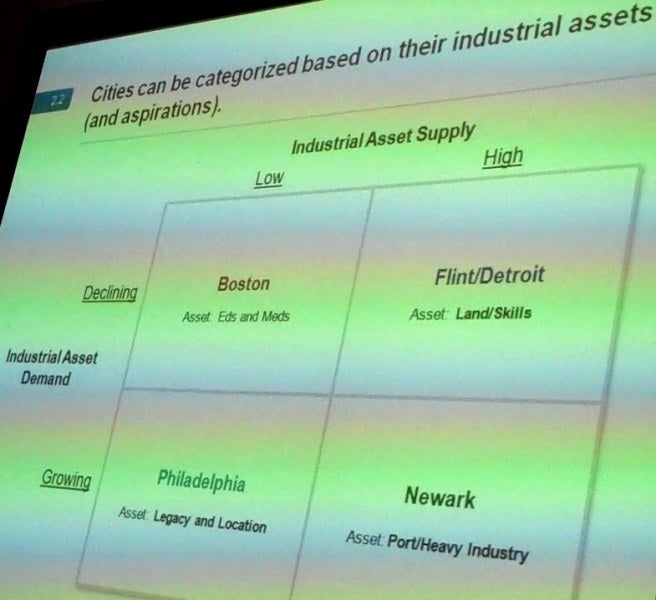

“For a city to succeed, it needs to understand specifically what it can do, what market segments it can compete in,” Lynch said. “[They] need to understand their core assets, and really have an inventory of those. But that’s actually not enough – they need to understand, as well, where they sit in the hierarchy of national cities. Everybody’s got eds and meds. Do you really have enough eds and meds that you’re going to drive prices? Everybody’s got infrastructure. Is your infrastructure really set up that you’re going to be able to lead in transportation and warehousing?”

Oil and bubbles

The increase in energy costs will have a profound impact, long-term, for industry in U.S. cities, said Lynch.

“If we ever really look at putting the costs on environmental emissions, those will favor – not just in the U.S., but in a number of countries – bringing manufacturing back,” she said. “One of the things that has supported all of these incredibly far flung international production networks is that people don’t really pay the full cost of energy, or environmental costs associated with those. The tide is changing on that, it seems.”

The real estate bubble also played a role, albeit a late-stage one, in driving manufacturing away from urban centers, Lynch noted. China, “or whatever country we’re blaming at the moment,” is not wholly responsible for the taking of U.S. jobs. Industrial land users have consistently been outbid by real estate concerns. In Los Angeles, for example, pre-boom industrial prices were about a third of residential. During the boom they rose to twice that of residential, Lynch said – or a factor of six, and that was in an era when residential was constantly rising.

Page concurred. “The housing boom was putting so much pressure on industrial land in Philadelphia, that it almost got to the point where decisions were being made [on worries] about what land should be converted from industrial to residential use, simply because we just didn’t know what the potential was.”

‘Slack space’

Page gave an example of the PIDC study’s methodology.

“We were very careful to collect both primary and secondary use,” he said. “This is important because we have some industrial sites where, as an example, we have one 10-acre site and four acres of it is clearly being used for manufacturing, but the other six acres are just sitting there dormant. If you just recorded that as ‘industrial’ as you would in a typical survey, you would miss those six acres of what we call ‘slack space.’ And we wanted to think about that slack space as a part of the opportunity to re-purpose that land in Philadelphia.”

In the 15 districts surveyed, there are about 16,000 acres, with some 9,400 acres zoned and being used for industry. About half of that is related to ports, freight and the airport.

Of the nine zones labeled industrial in Philadelphia, Page said they are recommending collapsing them into three.

“The other thing we’re really wanting to do with the study is to bring design into the discussion. In a city like Philadelphia, where it is basically maxed out in terms of development, if we’re doing an infill industrial strategy, we have to talk design. Because all these industrial sites are close to neighborhoods, and in some cases they are closer to assets like waterfronts.

“We have to get people to care about it. We have to get people to say that industry matters,” Page said. “One of the best things that we’ve done is hook up with the Community Design Collaborative to basically get industrial use as one of their big marketing efforts, where they do design challenges for industrial sites.”

“This is not some pie-in-the-sky nostalgic fantasy,” Wolf-Powers said. “There are some industrial users that desire, and can benefit from, urban locations. What they need is a stable land use environment and reasonable rents.”

What the early years of the 21st century have indicated, she said, is a renewed interest by cities in leveraging their industrial land for growth, employment, and revenue generation.

“It’s not just about economic development,” Page concluded. “What we make in cities is fundamentally a part, I think, of what a city’s identity and character is.”

Contact the reporter at ThomasWalsh1@gmail.com.

Further PlanPhilly coverage:

For a report from the APA conference about the session highlighting the zoning reform efforts of Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington, D.C., click here.

For a report highlighting ongoing efforts in the Lower 9th Ward, click here.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.