Delaware’s movement for fair fast food wages

Being able to support a family is the American dream but for many workers even putting in the maximum hours at a job isn’t enough to provide basic necessities.

In a tough economy where jobs are hard to come by, the fast food industry is one of the few markets readily filling positions. However, the starting pay is usually minimum wage, $7.25 an hour in Delaware. A few months of hard work might bump the pay to $7.50 or even $8 an hour if you’ve got experience.

Even working 40 hours a week, the monthly take home after taxes is less than $1,000, creating a very tight budget for a single person, let alone a family.

In August, more than 100 Delaware workers participated in a nationwide fast food worker strike to protest the “unfair” wages, gaining the attention and support from local and state leaders.

State Representative John Kowalko (D-Newark South) has met with fast food workers and supports their fight for a better wage.

“I go to these things for one very good reason, because at least these people can see someone who appears to have a better position of influence, who is out there standing with them, for them to keep moving and keep fighting,” said Kowalko.

Kowalko added that he doesn’t think its fair that hard working Americans are forced to live at the poverty level while corporations rake in multibillion dollar record profits.

“They are making very little money for compensation for strenuous and hard labor,” said Kowalko. “There’s a basic of fairness there when you calculate that against the money that the corporations that employs them is making.”

Fast food and govt. assistance

A new report from The University of California, Berkley highlighted the number of fast-food workers on public assistance, revealing that more than half are enrolled in some type of government assistance program.

“What it’s doing is draining resources from the rest of the tax payers who have a willingness to have resources available for sustaining those families and those people in need,” said Kowalko. “But it was never intended to be a support system so that it could be an excessive profitability of corporations.”

The gap between the cost of living and the salaries earned by the low-wage workforce is covered by taxpayers to the tune of around $7 billion a year in public assistance programs, according to the UC Berkley report.

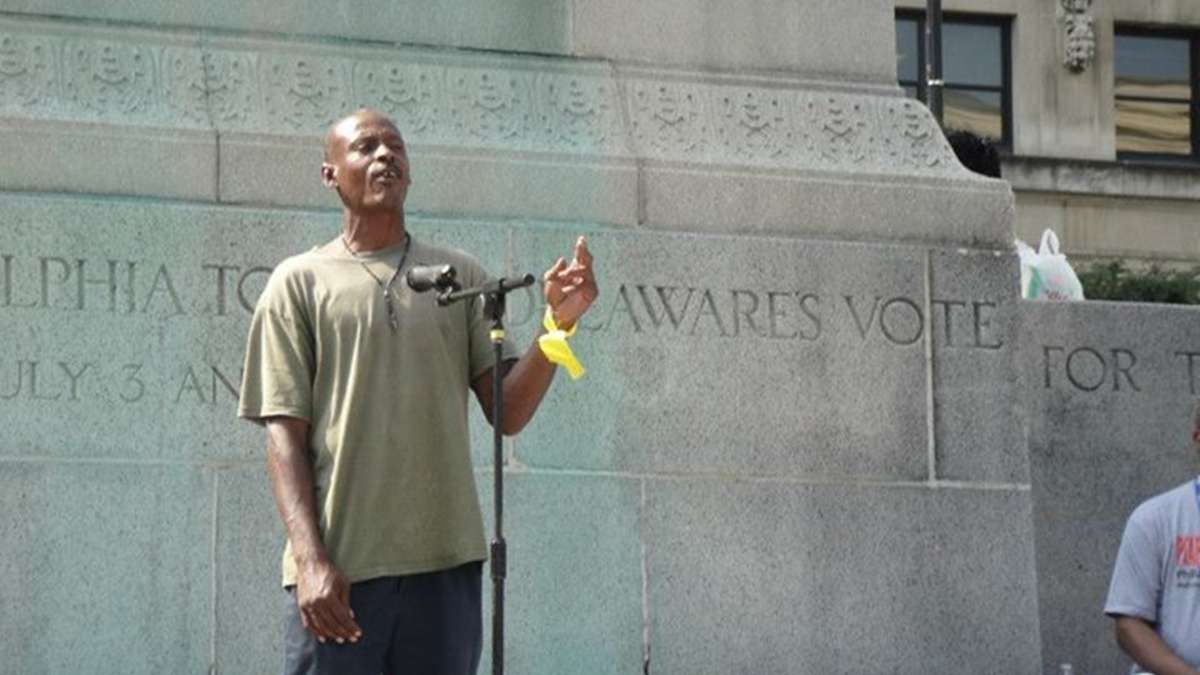

Howard White, a 43-year-old employee of a New Castle Wendy’s, said using food stamps and Medicaid is the only way he’s able to get by on $7.25 an hour.

White doesn’t own a home, a cell phone or a car. He rents a room, rides a bike to work and helps to support his daughter.

With food stamps, he spends about $200 a month on groceries.

“I can take care of the rent and then whatever your child needs, right there; I will have like $50 to hold on to until the next two weeks.”

White tried going to school but had to quit because it interfered with work. He said he likes his job at Wendy’s and is working toward a raise and a promotion.

“I get along with everybody. I’m a good employee, I work hard,” said White.

Educated adults make up workforce

Some argue that employees such as White represent a minority of the workforce and that fast-food jobs are largely held by teens earning some extra spending money after school.

However the UC Berkley report shows that 68 percent of front line fast food workers are adults.

Darlene Battle, executive director of the Delaware Alliance for Community Advancement helped to organize the fast food workers strike and continues to educate employees on the money they could be making, which Battle said should be $15 an hour.

“They work hard, they have families, some are in college, they pay rent, and they’re doing what every good American is doing with a little bit of money,” she said.

At $15 an hour, Battle said the employees would be able to get off food stamps and pay for their own health insurance.

Kowalko said they’d also have a little extra spending money to put back into the economy.

“You can’t stimulate the economy when you have a majority of your consumers without the resources to purchase the products you’re creating,” he said.

Fighting on

New Castle County Council President Chris Bullock also stands with Delaware’s fast food workers fighting for a better wage and said he’d like to bring awareness to the issue and start a conversation with franchise owners.

“I think it would be advantageous if we had a conversation with the franchise owners to see if we could work toward a common ground so we could have a higher ground solution,” he said. “That’s always the first step is to have the conversation with those who make the decisions. And then continue to fight the good fight.”

Both Kowalko and Bullock said other than trying to raise the state’s minimum wage, there’s not much that can be done on the legislative level.

“It’s a moral imperative for me,” said Bullock. “You can’t really force any legislative change because they are a free business enterprise which we support in this country. However when there’s a moral imperative involved, I think we should lift that above profits. Always lift people above profits.”

Battle said the next step is to stay organized, gain strength in numbers and call for action.

“We have to continue to walk out of these restaurants, and continue to hold press conferences and continue to educate our state officials as well as on a national level,” she said. “And, the biggest thing is to call an investigation. Why are the people making so little when this is a multibillion dollar company?”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.