Delaware gets a ‘B’ for child sex trafficking response

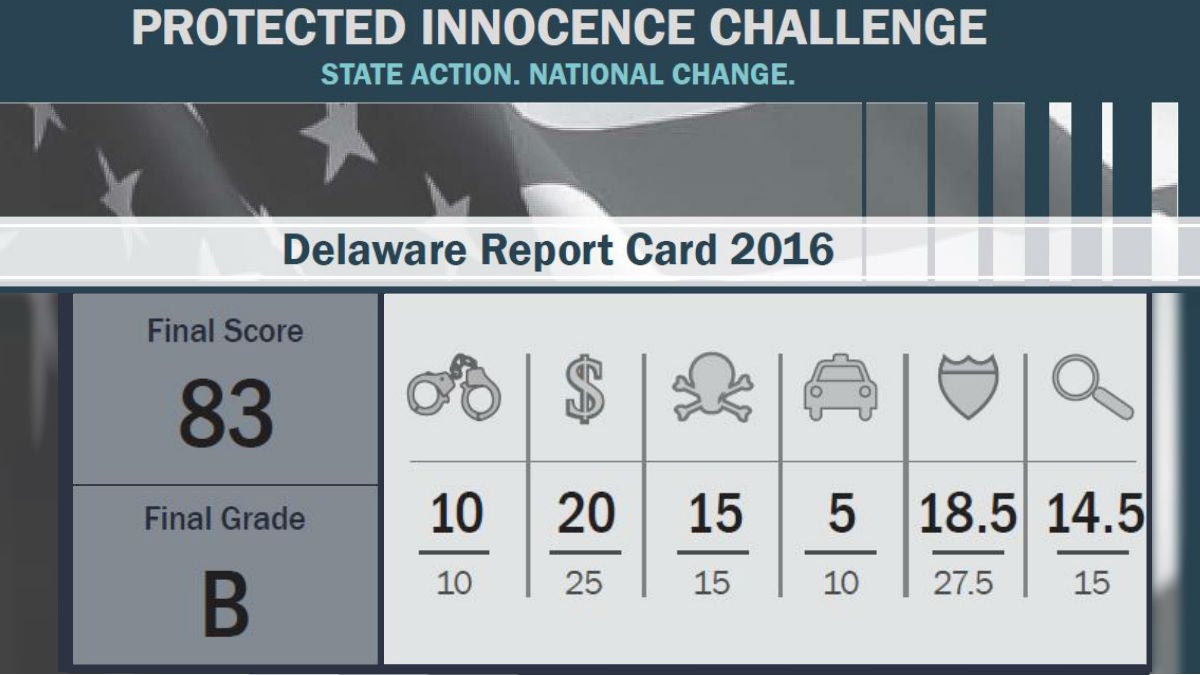

This screen grab shows Delaware's 'B' grade on the Protected Innocence Challenge report. (photo courtesy Shared Hope International)

Delaware is taking necessary steps to address child sex trafficking in the state, but still has language in its laws that could affect a minors’ ability to receive support and protection, according to a report released by a national organization dedicated to eliminating sex trafficking.

Shared Hope International gave Delaware an overall B grade for its domestic minor sex trafficking laws. This is a major improvement from its 2011 D grade—but some improvements should be made to ensure the protection of children who are commercially sexually exploited, the organization reports in its Protected Innocence Challenge.

“The state report cards are meant to be very individual. We want the states to, and really the goal of the report cards is, identify where progress has been made and to acknowledge that progress, but also identify where gaps remain so states can keep improving and move toward having that solid legal framework of protections in place for child sex trafficking victims,” said Christine Raino, director of public policy.

“The Protected Innocence Challenge is meant to be a call to action to states. We don’t just identify the gaps, but in order to grade the states we do an in-depth analysis of each states’ laws and we use that analysis to provide the states with tools to address the gaps.”

The Protected Innocence Challenge was designed after the organization conducted research on domestic minor sex trafficking in the U.S., which found the issue could not simply be addressed at the federal level, because the volume of cases cannot all be prosecuted federally and there are many more state prosecutors than federal prosecutors. The report began in 2011, and has graded each state every year since.

The report analyzes six areas of law, including criminalization, criminal provisions addressing demand, criminal provisions for traffickers, criminal provisions for facilitators, criminal justice tools for investigation and prosecution and protective provisions for victims.

The organization conducts an in-depth analysis of each states’ laws, and completes a 40 to 60 page analysis report to grade each state. The states receive an overall score and grade, but also a breakdown of scores in each area of law.

The grades reflect only the statutory analysis of state laws, and do not measure implementation and enforcement of laws.

Yolanda Schlabach of Zoë Ministries, an organization dedicated to eliminating sex trafficking in Delaware, said she’s aware of 10 adult women identified as victims in the state, but no minors. In addition, she said only three traffickers have been arrested.

“That does not mean it is not happening,” Schlabach said. “It simply means that we are not trained statewide throughout our organizations and agencies to recognize it, and we aren’t aware of a referral base suited to meet the needs of this population. Legislation is a great place to start, but it’s only the beginning.”

Raino said improvements have been made nationwide. In 2011, 26 states received a failing grade, and no state received an A. This year, no state received an F and seven states received an A.

The organization provides specific recommendations for anyone who wants to answer the call to action, and use it as a tool to improve their state’s laws.

Delaware’s law clearly criminalizes child sex trafficking and has a range of protections in place specific to child sex trafficking victims, Raino said.

The state received a perfect score in the area of criminalization, as domestic minor sex trafficking is criminalized without requiring proof of force, fraud or coercion when the victim is a minor.

Delaware also received a perfect score in the area of criminal provisions for traffickers, who can receive up to 25 years in prison for trafficking a minor.

However, Raino said her organization has concerns about language in the laws that leave child victims vulnerable. Delaware received an 18.5 out of 27.5 for its efforts to protect victims—an area where several states fall behind.

Delaware overhauled its trafficking laws a couple years ago, which improved areas of criminalization and victim protections, Raino said. However, it also established the requirement of an identified trafficker in order for a commercially sexually exploited child to be recognized as a child sex trafficking victim, she said.

“As we talk about building protections for child sex trafficking victims and doing the hard work required to move forward in that area we need to be clear how we’re defining a child sex trafficking victim,” Raino said.

“Under federal law any commercially sexually exploited child is identified as a victim of trafficking, but we’re finding the states aren’t aligning with that same definition. As we encourage states to develop specific protections for child sex trafficking victims we’re also encouraging states to make sure their definitions aren’t leaving some vulnerable youth out of that definition and potentially limiting their access to services and protections.”

Some of the victims most likely to be impacted by third-party controller requirements are runaway and homeless youth, who may be exchanging sex acts in order to survive, she said. These youth often are commercially sexually exploited, but not identified as trafficking victims, Raino said.

In addition, individuals who are emotionally attached to abusers are not likely to acknowledge they have been trafficked, she said.

Children with an identified trafficker are protected and receive specialized services through child welfare or family court. Trafficking victims also receive several other protections, including the ability to communicate with the courts through video rather than testimony in the courtroom.

However, children who do not have an identified trafficker are subject to criminalization for prostitution or loitering, despite being minors.

“We cannot protect children against what we are charging them with! When states prosecute victims for crimes committed against them, they learn that those in authority cannot be trusted—that “we” are not dependable. That we have nothing to offer but more blame, perpetuating the cycle of hopelessness,” Schlabach said.

“But if we can build a system, beginning with effective legislation, that offers trauma-informed services and housing, we can create a culture of healing and hope. Without it, we only send them back into the arms of their predators—and more often than not, the devil you do know is more familiar, and therefore appealing, than the devil you haven’t met yet.”

Among Shared Hope’s several recommendations, it asks legislators to ammend the definition in the law so all commercially sexually exploited children are identified as victims. In addition, the organization recommends a mandate that all commercially sexually exploited children receive specialized services.

“The concern that remains for Delaware is there is still the possibility to charge and criminalize a child, and when we’re charging kids with an offense directly related to their own criminalization it sends the wrong message—it sends the message that these child victims are somehow responsible for their own victimization,” Raino said.

“That’s the reason the goal post of moving toward non-criminalization and having avenues to access those specialized services without having to charge kids, is a really critical goal post for every state.”

Schlabach said while she agrees it’s important to allow victims access to services once identified as trafficking victims, there currently are very few services available.

“The survivors in our state will only receive services if there are some,” she said.

“At this point, Delaware has no specialized housing for these survivors, and very little to offer in the way of education, life skills or transportation to and from appointments, therapy—all of the necessary components for recovery and success after exiting “the life.” Where do we expect law enforcement or other agencies to send victims that are appropriate for their compound trauma, detox and immediate medical needs?”

Delaware received both high and medium scores in other areas of the report card.

The state almost received a perfect score for its ability to utilize several criminal justice tools for investigative purposes and prosecution. Wiretapping and use of the internet can be used during investigations of potential human trafficking cases, according to the report. However, while development of training materials and training for law enforcement is authorized by law, it is yet to be effectuated, the report states.

However, a recent sex trafficking conference in Dover included training for law enforcement. It is not clear what was involved in the training session and when the ideas will be enacted officially.

Delaware received a 20 out of 25 in the area of demand. The sex trafficking law does not apply to buyers, and for the most part, individuals who patronize a prostitute only face a fine of about $500, no matter how old the seller is. However, an individual can receive up to 15 years in prison for patronizing a victim of sexual servitude.

Shared Hope is recommending that Delaware enacts a law criminalizing the act of buying sex with a minor with higher penalties. The recommendations also include distinguishing between patronizing a minor versus an adult.

Schlabach said she agrees there’s a need to decrease the demand side of sex trafficking by more consistently and heavily prosecuting the buyers of commercial sex.

“We need higher penalties that can be realized through prosecutions,” she said. “The demand side must be addressed. While much of the passing and implementation of legislation is a process of awareness, training and protocol enforcement, a law is ineffective until it is realized through the arrest of perpetrators and recovery of victims.”

Delaware received a 5 out of 10 for its efforts to criminalize facilitators. The report states the human trafficking law does not include assisting, enabling or financially benefiting from sex trafficking. However, transporting a minor in furtherance of sexual servitude may apply, and the facilitator could face up to 25 years in prison, the report states. Promoting prostitution in the second degree may also apply to facilitators who supply the venue for sex trafficking minors, and they could face up to 5 years in prison. Share Hope is asking Delaware legislators to enact laws that penalize facilitators as well.

Raino said while the U.S. has made significant strides to address child sex trafficking, more work must be achieved to protect minors.

“Like many states Delaware has work to do in terms of developing protective responses for child sex trafficking victims that moves away from that punitive response and provides access to specialized services,” she said. “We recognize this is challenging for states, but it’s also an important goal post all states need to be moving toward.”

You can read the Shared Hope International report on Delaware below:

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.