‘Desperation and uncertainty’ for Delaware family one year after fleeing Ukraine

The family settled in Poland with their three young children after the invasion. They remain hopeful, but know the fate of Poladko’s homeland remains uncertain.

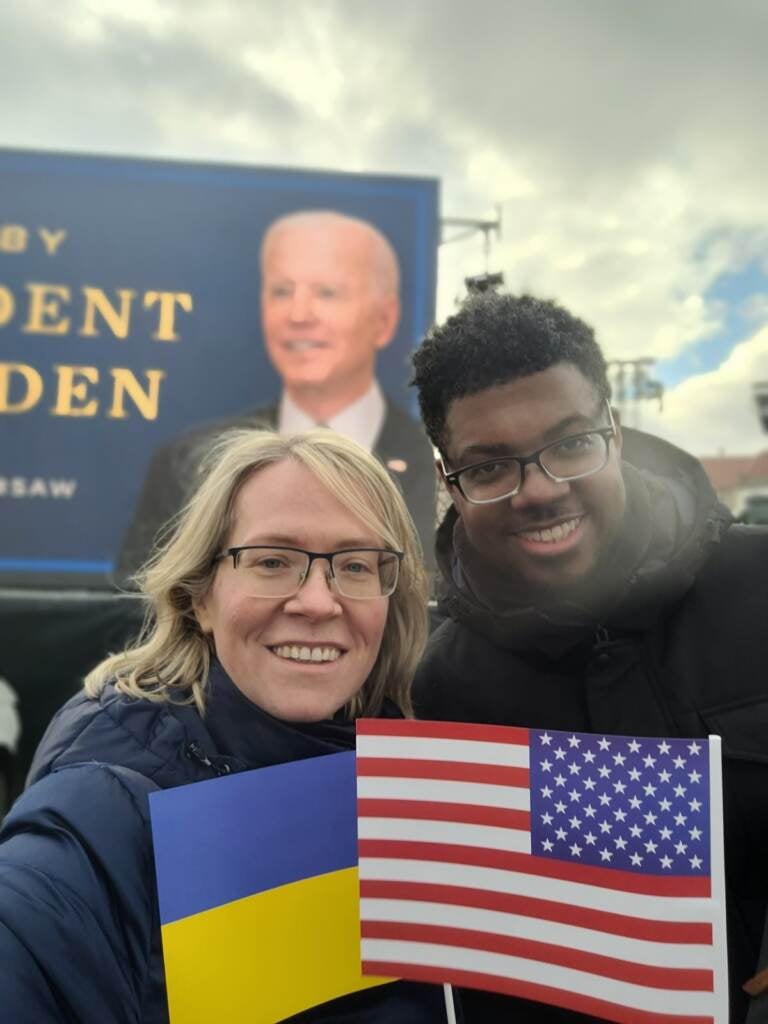

A year after the invasion, Tatiana Poladko and Atnre Alleyne are trying to have the semblance of normal life with their children in Poland. (Courtesy of Atnre Alleyne)

A year ago, if you had told Wilmingtonians Tatiana Poladko and Atnre Alleyne they would be in Warsaw this week watching President Joe Biden give a stirring wartime speech, they might have questioned your sanity.

But there they were Tuesday evening, bundled up with thousands of others in the frigid air outside Poland’s Royal Palace.

They watched and photographed fellow Delawarean Biden pass within 15 feet of them before taking the stage and pledging that “brutality will never grind down the will of the free, and Ukraine will never be a victory for Russia’’ during an address televised across the globe.

“The whole thing is surreal,’’ Aleeyne told WHYY News this week.

For Alleyne and Ukrainian native Poladko, the last 365 days have unfolded in ways they never could have imagined.

On Feb. 24, 2022, when Russian bombs first fell on Poladko’s homeland, explosions near their home in a peaceful suburb on Kyiv’s outskirts forced them to evacuate and triggered an odyssey that sometimes feels like it will never end.

The couple, with their three young children and Poladko’s father in tow, initially spent nearly a week dodging artillery shells and avoiding Russian tank blockades while fleeing the besieged nation with more than one million others.

Then they spent months resettling in Warsaw — about 430 miles from Ukraine’s western border with Poland. They got their kids into schools and activities such as tennis and swimming while continuing to run their educational nonprofit TeenSHARP virtually, all the while pondering whether to return to the United States, or wait out the fighting from Poland or elsewhere in Europe.

Poladko returned to Kyiv over the summer to fill out paperwork for her travel documents and see friends, but the experience proved unsettling as nightly air raid sirens jarred her back to the nightmarish first days of the invasion by Vladimir Putin’s military.

Now they’re in limbo, hoping for a peaceful resolution while lamenting the tens of thousands of Ukrainian soldiers and civilians killed, the families torn apart by the conflict, the destruction of cities, while dreading the possibility that Russia might conquer part or all of Ukraine.

Poladko has friends whose loved ones have been killed. Families have been blown apart, scattered across Europe. Students at their children’s school in Ukraine now take classes in the basement.

“It’s just such a sense of uncertainty and desperation, honestly,’’ Poladko said. “If you really begin to understand the human predicament and lots of different dimensions of it right now.”

‘Happiness is never absolute, because you know the cost of it’

Alleyne and Poladko talked to WHYY News for about a half-hour over four late-evening calls that were interrupted by dropped signals.

At one point, Poladko had to leave the call to attend to the cries of their 3-year-old Taras. They have two other children: Zoryana, 8, and Nazar, 4. Poladko’s 82-year-old father, Eduard, has since returned to Ukraine.

Poladko said that overall, she’s “very hopeful and continuously proud’’ of her fellow Ukrainians and of “the government response and just kind of relentlessness and savvy that they’re demonstrating.’’

She pointed out that those who are not fighting have volunteered to raise money for military supplies such as drones. Many have taken second jobs to help their families survive, even as power outages from the constant shelling have made the winter a living hell for so many survivors.

Yet, too often, dizzying, disparate thoughts fill her mind.

“Some days you feel like we’re about to have a victory day, and other days you just like fall into despair,’’ she said. “That kind of pendulum swinging really very describes the emotion of the past year, continuing into today. Happiness is never absolute, because you know the cost of it.”

For example, there’s optimism because Russia isn’t gaining significant ground despite intensifying the bombardments, and that Biden this week announced more aid, including 700 tanks.

Yet she hears the despondence from the front and President Volodymyr Zelenskyy’s calls for even more firepower such as American fighter jets.

One friend who raises money for drones recently told Poladko how several, even dozens, sometimes get shot down in one day.

“I was flabbergasted,’’ she said. “Here we are, so happy each time we raise $3,000 to buy one drone, and the realities are just like so much more intense than honestly, any one of us imagines.’’

She also lives in fear for her father, who recently caught pneumonia and had to be hospitalized. Yet he’s happier in Ukraine, with friends and his wife.

“Being in Poland, it is not easy for the elderly,’’ she said. “So many people I communicate with who have their elderly parents here all talk about the profound loneliness that they feel. So I’m glad he’s with his wife and he’s in a house that has some land, and he’s able to stay busy in this way, taking care of trees and whatever plants that they have.”

Despite her unsettling visit in July, Poladko had planned to return to Ukraine to pick up her travel papers and visit friends.

But her plans collided with a major Russian offensive that has continued.

“Quite frankly, I’m more scared than I was in the summer by the thought of going back. So I’ve been dragging my feet.”

She also learned that an agency in Warsaw can process the paperwork and have documents mailed to Poland, “so I don’t think I’ll be going right now.”

‘This will be, unfortunately, kind of a long slog’

Poladko realizes the future remains uncertain, and the fate of her homeland is precarious.

“Thinking this could go on for five years is probably a sobering thought to have,’’ she said. “But I cannot bring my mind there. Honestly, not yet.”

She and other Ukrainians “think in terms of seasons,’’ getting through the winter and into the spring, with more weaponry to support a counteroffensive against the Russians.

“We’re all just putting so much hope and prayer that there is some type of resolution.

But on the other hand, we also understand that pushing Russians off of Ukrainian sovereign territory does not mean that missiles stop flying in.”

Alleyne said he’s come to terms with the reality on the ground, that Russia has withstood the economic sanctions, the international condemnation, and the loss of so many of its own soldiers.

“Now we, like others. believe this will be, unfortunately, kind of a long slog. That part of it is very clear to us and many others,’’ he said.

“We’re all very hopeful and we’re all believing that there will be victory. It will take longer than a lot of us predicted or want but people have to stay committed and consistent to this fight.”

Biden’s trip to Ukraine this week — his first since the invasion — reinforced the message that the West stands with Ukraine, Alleyne said.

So did his speech in Warsaw.

“The world leadership on display related to this issue has been a beacon in really, really dark times and really scary times,’’ he said, noting that he and thousands of others, many holding Polish, Ukrainian, and American flags, waited outside for hours to hear Biden speak.

“That’s why they did it. It’s very refreshing. And President Biden is recognizing the significance of this historical moment.’’

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.