County courts grapple with rollout of Pa.’s new rules for firearms in domestic abuse cases

Anyone subject to a final protection from abuse order after a contested hearing must turn over their firearms within 24 hours.

The Delaware County courthouse in Media, Pennsylvania, is seen on April 11, 2019. In the county in 2017, there were 206 protection-from-abuse cases that ended with a stipulation or agreement between the parties, 187 final orders granted after a hearing before a judge, and 147 final orders denied after a hearing before a judge. (Ed Mahon/PA Post)

This article appeared on PA Post.

—

Lycoming County Judge Joy Reynolds McCoy had a light docket one morning earlier this spring, but the single hearing before her was timely.

Firearms were a sticking point in the protection from abuse case and an admitted bargaining chip: the man offered to drop his petition, presumably allowing his ex-girlfriend access to her gun, in exchange for a response in kind.

She had an attorney, he did not and they agreed to delay the hearing.

McCoy rescheduled them for yesterday – one week after Pennsylvania’s new laws on PFAs, domestic violence and firearms took effect.

Now, anyone subject to a final protection from abuse order after a contested hearing must turn over their firearms within 24 hours to law enforcement, an attorney, a licensed gun dealer or armory.

Before, the law required relinquishment only if specified in the PFA, which is good for as long as three years. And it allowed the accused abuser 48 hours to turn over guns to a third party (which could include a friend, so long as they signed an affidavit stating they didn’t live with the person, wouldn’t return the firearms, etc.).

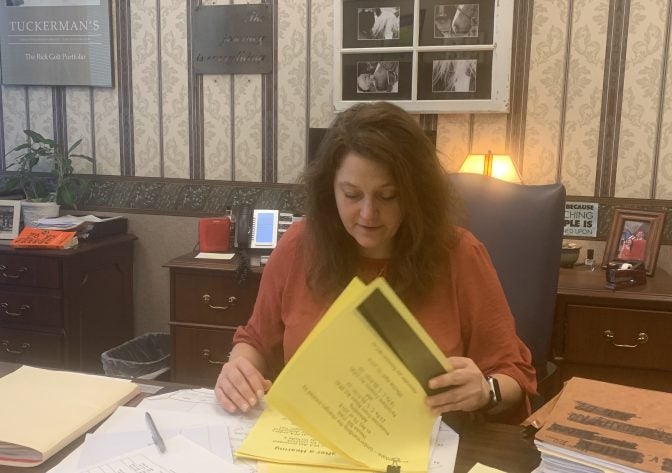

In chambers after court hearings concluded, McCoy, who’s helped the Pennsylvania State Police train the state’s sheriffs and Lycoming police chiefs on Act 79, the question came up of when/whether to apply it to such cases initiated prior to April 10.

McCoy acknowledged the legislation’s wording could leave judges leeway as far as applying the new law — or not — to cases that began before the law’s effective date. But she — and others — say that issue hasn’t come up in the courtroom, at least not yet.

“Under the old law, I had discretion and under the new law, I’m required to do it,” she said. “If I don’t say on the record that I’m applying the old law, there’s no way to challenge it.”

Old law or new, the judge still has to weigh the credibility of the people involved in each case.

In this situation, the gun owner got a concealed carry permit shortly after the relationship ended and before seeking a PFA, she testified, out of concern for her own safety.

“That does cause me concern, that she went out and got a permit to carry after their relationship ended,” McCoy said. “Just a little unsettling that that would be someone’s reaction. But if you are genuinely concerned for your own safety, I guess that’s a legitimate reaction.”

There isn’t consensus or consistency among counties or even judges in the same courthouse, it seems, on how they’ll apply Act 79 changes and how much of a difference it will make in their approach, according to judges, advocates, and plaintiffs’ and defense attorneys handling cases in 31 counties, including Erie, Westmoreland, Philadelphia and its suburbs, and multiple in the commonwealth’s capital, northeastern and coal regions.

In some counties, the law codifies some procedures already in place. And it leaves enough open to interpretation that there will be an adjustment period statewide.

“There’s a learning curve here between the enactment of the new changes, and when everybody else understands what the limitations are, what can or cannot be asked of the court in an order,” says Stephanie Longenberger, an attorney for MidPenn Legal Services who represents PFA plaintiffs in Lancaster County.

That’s not unusual, but will have implications for people involved in these types of cases. They include those meant to be protected by Act 79 — the people who fear harm from a loved one or current or former partner — as well as defendants. They’ll be unsure what, exactly, to expect as counties figure out how to implement the new law.

Had the case referenced above proceeded as scheduled a couple weeks ago, the gun owner stood to recover their weapon if McCoy declined to order a final PFA or the parties struck an agreement. The same is true under the new law.

The difference: Before, McCoy could’ve ordered a standing PFA that didn’t deal with firearms. But with Act 79 in place, orders have to ban possession and require relinquishment of guns, ammunition, licenses to carry and other weapons.

Now, Pennsylvania law more closely matches federal statute in that respect because firearms relinquishment must be part of every final contested PFA order in the commonwealth.

The changes to state law are intended to clarify things.

But, it’s still complicated, acknowledged Lancaster Judge Leonard Brown III.

“It does get very confusing, especially with overlapping federal law,” said Brown, one of three Lancaster judges who handles PFAs.

As of April 16, Brown hadn’t run any PFA hearings since Act 79’s effective date — and even judges and lawyers who had handled such cases since then had few, if any, where the new law really mattered much.

Brown said he hadn’t considered whether to apply the new law to matters initiated before April 10.

“I don’t see it being a big issue with the way we’ve [already] been doing it in Lancaster County,” Brown said. “I’ve been doing this for eight years, and I have not seen an issue with the firearms actually being taken.”

In the same courthouse, Judge Merrill Spahn was quick with his answer to whether he’ll apply the new law to older cases:

“Yes,” Spahn said. “If the overall intent is to protect, then I’m going to err on the side of caution.”

Delaware County Judge Dominic Pileggi says he intends to apply the law to all cases regardless of when they started, but doesn’t expect it to be an issue often.

“I don’t think [Act 79] will have much of an impact on how we deal with firearms,” said Pileggi, a longtime state senator whose successor, Tom Killion, R-Delaware, sponsored legislation that led to Act 79. “That has not been an issue in any requests for continuance of a hearing … in the last three years, in my experience.

“I have yet to have maybe one or two in the last few years where the defendant has said, ‘I don’t want to give up my firearms’, or ‘I need my firearms’, or question it,” he added.

Judges agreed that Act 79 might be important, but will affect a relatively small number of cases.

McCoy says about 15 percent end up with an order, more by agreement if they haven’t been withdrawn or dismissed because there’s a no show on one or both sides when the court date arrives.

That’s relatively consistent across counties, according to AOPC stats and interviews and observations of courtrooms in a handful of counties during the past few weeks.

Some counties encourage agreements by design, in a way.

Westmoreland County Judge John J. Driscoll, for example, took the bench about 90 minutes past his scheduled start times April 1 and April 2 — in part, his court assistant said, to give parties a last shot to work out an agreement through their attorneys before court begins.

And Delaware County has a court-appointed special master to work with plaintiffs and defendants in cases where neither side has an attorney. The special master explores whether they are interested in an agreement without a full hearing. If so, the three of them draft one together and send it to a judge to review and sign.

Attorney Jane McNerney, one of the special masters, was working on a recent Thursday morning on a case in which — as often happens — the two sides weren’t interested.

So, McNerney sent them to Pileggi for a final hearing. But other cases she did resolve.

McNerney works with people down the hall from Pileggi’s ornate courtroom with a high ceiling and red carpeting, with a few dozen other PFA plaintiffs and defendants waiting to talk to her.

Some cases had been continued for months with a temporary protection order in place — which is sometimes done in Delaware County to give people a cooling-off period in what Pileggi described as a “highly emotional” situation.

In one case, a defendant brought a certificate showing he had completed anger management. McNerney complimented both sides for working “hard to bring some semblance of cooperation.” She asked a series of questions about the woman’s safety, was satisfied with the answers and the plaintiff withdrew the petition.

Firearms came up a few times in the sessions on Thursday — but only when McNerney asked about them. Other issues came up more often. The logistics of custody exchanges took up the most time, which held true in other courtrooms.

Brown and Spahn also said firearms rarely are sticking points. Brown said the exceptions he’s seen are cases involving a law enforcement officer who needs a firearm for work.

But that doesn’t hold true in every county — or every stage of a case.

Some lawyers say it doesn’t exactly start off that way much of the time.

“Particularly when you get closer to hunting season or you’re dealing with cases where typically the defendant has gone deer hunting, it becomes a very significant issue for them … [and] a huge sticking point in the order,” Longenberger said.

Laurie Baughman, MidPenn’s deputy legal director, says it tends to vary among the 18 counties in that agency’s coverage area, with relinquishment being a bigger deal in rural areas.

Longenberger, Baughman and McCoy also noted the potential for relinquishment to be an agitating factor in some cases. There is still some flexibility to keep other components of a PFA and allow weapons to remain in a defendant’s possession if there’s an agreement in the case or a temporary order is extended.

McCoy says while firearms already are a frequent bargaining chip in her courtroom, she expects cases to settle by agreement rather than an order in a contested matter.

“Weapons in this county, specifically, for hunting are a big issue in PFA cases because such a large percentage of our population hunts,” she said.

In that one case in McCoy’s courtroom Wednesday, Act 79 ended up being irrelevant because only one side appeared at the final hearing — and it was the gun owner.

“I have no idea what I would have done if I had heard the complete story,” McCoy said. “It made my job easier that he didn’t show up. I didn’t really have to make a decision.”

PA Post reporter Ed Mahon contributed to this story.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.