Concrete is a big contributor to climate change. Penn researchers say they can shrink its footprint

Concrete reabsorbs some of its carbon emissions over time. Alternative ingredients and 3D printing could help supercharge that by making the finished concrete more porous.

Listen 1:12

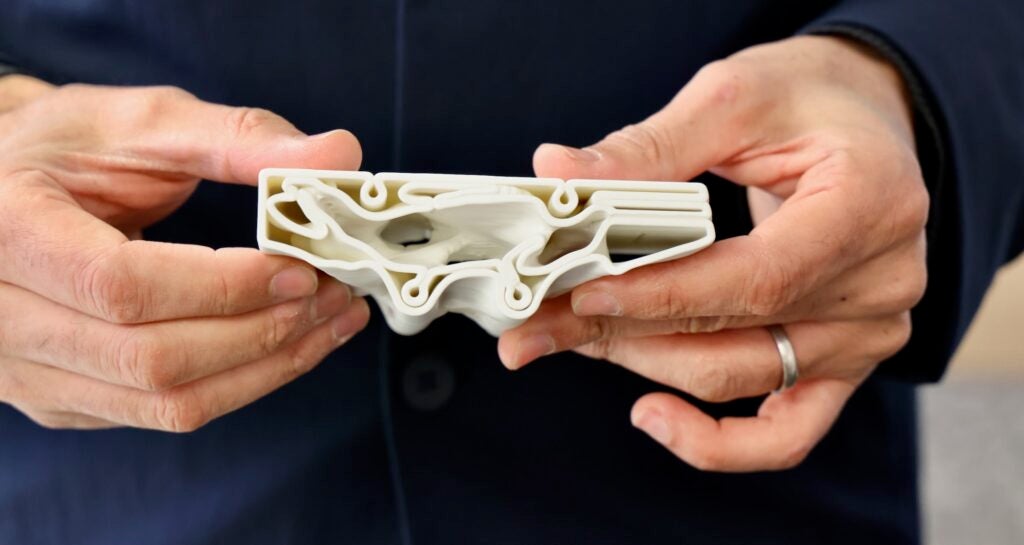

Masoud Akbarzadeh (left), a professor of architecture at the University of Pennsylvania, is working with students to design concrete structures that use as little concrete as possible while remaining strong. He holds a model of a structure based on the wing of a dragonfly. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

This story is part of the WHYY News Climate Desk, bringing you news and solutions for our changing region.

From the Poconos to the Jersey Shore to the mouth of the Delaware Bay, what do you want to know about climate change? What would you like us to cover? Get in touch.

The world uses billions of tons of concrete every year. Concrete production is a big contributor to climate change, making up about 8% of global carbon emissions each year.

Researchers around the world are working to find ways to make concrete greener, including at the University of Pennsylvania, where teams are 3D printing streamlined concrete forms and developing alternative concrete mixtures that absorb more carbon from the air.

“Anything we can do to reduce emissions from the building sector is going to combat global temperature rise and climate change,” said Ryan Welch, a principal and research director at the Philadelphia architecture and planning firm KieranTimberlake, who estimated the emissions associated with the Penn researchers’ designs.

Optimizing shapes to use less concrete

Masoud Akbarzadeh, a professor of architecture at the University of Pennsylvania, is working with students to design concrete structures that use as little concrete as possible while remaining strong.

“In order to reduce the carbon footprint, you need to reduce the use of material that would last through the life cycle of a building,” Akbarzadeh said.

Akbarzadeh’s team models the flow of forces through a structure, such as a bridge, floor, beam or column. They then design a concrete form that bears weight most efficiently, capitalizing on concrete’s strength, which is compression.

“[The force is] just pressing against the cross section, always, all the time,” said Akbarzadeh. “That’s allowing you to take advantage of the entire cross section of your material, and you can remove … excessive material from this, so it becomes super lightweight, but in the meantime takes a lot of force.”

A concrete pavilion built outside the Pennovation Center in South Philadelphia demonstrates this technology. The ceiling is organic-looking, hollowed out with rounded voids and caverns not typically seen in building architecture.

“If you look at natural structures, they’re actually full of these cavities,” Akbarzadeh said.

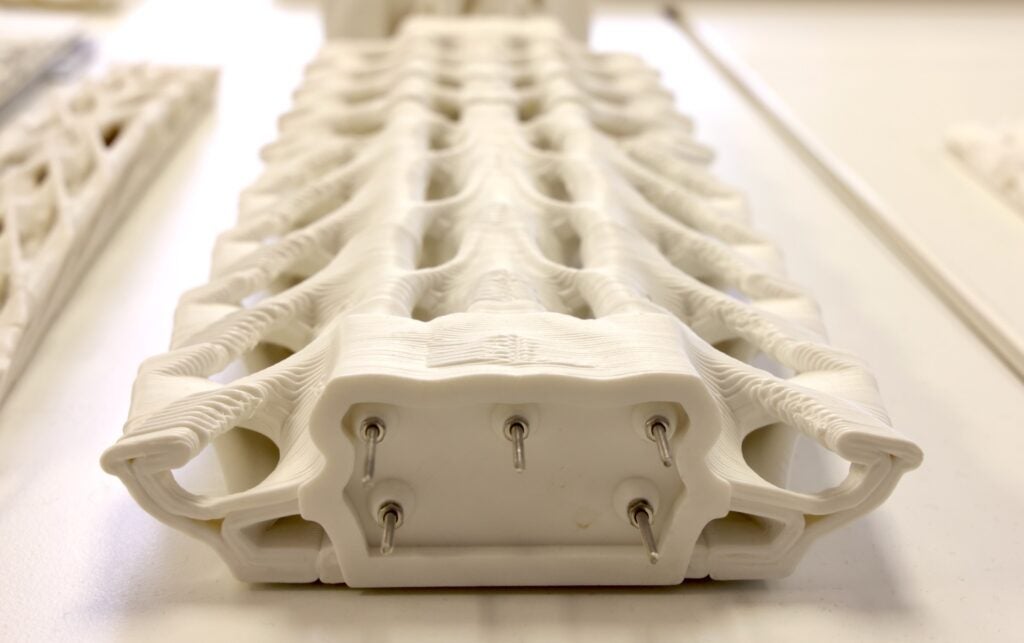

It would be difficult to create these complex structures by pouring concrete into a mold, Akbarzadeh said. Instead, his team 3D prints the structures in pieces, then assembles them on site.

Akbarzadeh said minimizing concrete use is not the only way that 3D printing reduces emissions. Printing, rather than pouring, sections of concrete buildings eliminates the need for concrete forms. It can also reduce the need for steel reinforcement inside the concrete, he said. Akbarzadeh’s structures do include some steel cables, but they are stretched inside thin tunnels in the concrete, rather than embedded in the concrete itself, making them easier to remove during demolition.

“We don’t have the conventional cages of rebars that could go within the concrete that makes it really difficult to recycle down the road,” he said.

Akbarzadeh said his team’s designs could be used to print floors of buildings or bridges.

Changing the mix to absorb more carbon

Another Penn researcher, Shu Yang, has been working on developing more climate-friendly concrete mixtures.

The production of conventional concrete releases carbon emissions in two main ways. Cement, the powdered substance used to bind sand, gravel and other elements together, is made from limestone or similar substances heated to very high temperatures. This process is energy-intensive and currently powered largely by fossil fuels, which emit greenhouse gases. The process also releases carbon dioxide directly from the raw material as it is converted into quicklime.

But conventional concrete reabsorbs and traps some of this carbon from the air over its lifetime. Yang’s team is working on supercharging this.

Her team recently published a paper describing a concrete mixture replacing a portion of the cement with diatomaceous earth, a type of sedimentary rock made from fossils.

They found the new mixture absorbed 42% more carbon from the air than conventional concrete when placed in a carbon dioxide-rich environment for a week, because the diatomaceous earth made the concrete more porous and maintained that porosity over time, Yang said. In conventional concrete, the carbon absorption process fills these tiny holes, blocking the concrete’s ability to absorb more, she said.

The diatomaceous earth mixture can be 3D-printed rather than poured, which Yang said increases its surface area and allows it to absorb even more carbon compared to traditional concrete.

So far, the concrete mixture has been printed into prefabricated sections Yang said could be used to assemble a floor. Yang is seeking to patent the mixture for commercial use, but said it will require more demonstration and testing, including in different environments, before it will be ready for use in buildings.

Putting the pieces together

Concrete structures combining Akbarzadeh’s complex, light-weight designs with Yang’s carbon-absorbing mixtures could dramatically reduce the carbon emissions associated with construction, according to a lifecycle analysis by KieranTimberlake.

Production, installation and the eventual demolition of a theoretical 3D-printed, carbon-absorbing 10-meter by 10-meter concrete floor could produce 50 to 90% less planet-warming emissions during its “lifecycle” compared to a conventional concrete slab floor, Welch said.

Welch estimates such a floor would require half the concrete of a conventional slab floor, while having 80% more surface area, increasing its capacity to absorb carbon from the air.

Welch said the exact emissions would depend on the source of electricity used to create and print the concrete, how far the prefabricated concrete forms would need to be transported to a building site as well as variations in the concrete recipe.

By combining this concrete with building designs that are hyper-efficient to heat and cool, it could be possible to create buildings that are “carbon-negative” by the end of their lifecycles, Akbarzadeh said.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.