Coatesville parents, students confront school officials over response to racist incidents

School district officials in Coatesville held a special meeting where they got an earful from students and parents about recent racist events that rocked the high school.

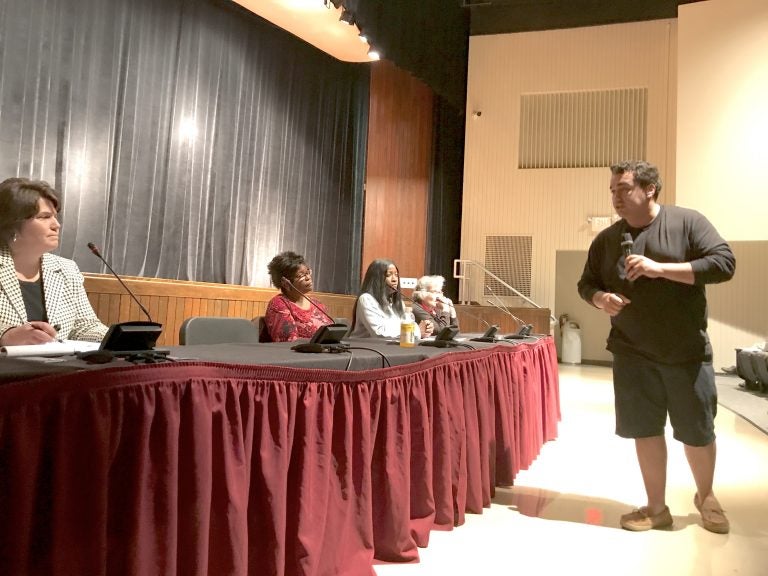

John Hillworth, a graduate of Coatesville Area High School, was among about 100 people who came out for a meeting with school district leaders about recent racist incidents. (Laura Benshoff/WHYY)

School district officials in Coatesville held a special meeting Monday night where they got an earful from students and parents about recent racist events that rocked the high school.

About 100 parents and students gathered in the auditorium of the Coatesville Area High School to air their feelings on two recent incidents: pictures of students holding up racist carved pumpkins and of a brown baby doll, hung up by its neck in a locker room. Reports of both swept through the school community this month.

However, much of the back-and-forth at Monday night’s meeting focused on whether students who recently protested the Chester County school district’s response should be disciplined.

Last Friday, students organized a school-approved “unity rally.” Afterward, some students walked out of class where they joined community members waiting outside. The protesters linked arms and marched around the school for several more hours.

Coatesville is one of at least three school districts in the Philadelphia area struggling to deal with incidents of racism in recent weeks. In Washington Township, New Jersey, students protested after racist text messages led to a fight in the halls. In Quakertown, Pa., reports that both students and parents hurled racist slurs at visiting Cheltenham School District cheerleaders prompted soul-searching by administrators.

In Coatesville, Terrell and many other parents at the meeting urged leniency for protesting students who’d found a peaceful way to vent.

“The point of our protest was to get the point across that our voice was not being heard, and if we come across in a way that seems disrespectful to the board … it’s going to keep us from building a relationship that needs to be built right now,” said senior Gabriella Vetter, who helped organize the protest.

Many in the audience described the the protest as a positive, affirming experience and directly criticized district superintendent Cathy Taschner. The school official challenged that narrative, saying protesters had banged on classroom windows, interrupting other students in class. Taschner also highlighted the outlets the school had already created for students to process the hurtful messages in the weeks after they occurred, including small group discussions with trained facilitators.

“There are different ways for people’s voice to be heard and there’s ways to do that in a safe environment,” she said. “And that means also not interrupting the education of anyone else.”

The students who walked out received unexcused absences, which could result in suspensions if they already missed too many classes, according to high school principal Michele Snyder. Families have the option of appealing that decision.

The meeting’s focus on the aftershocks in some ways overshadowed the racist events themselves, although parents did criticize the district for not disciplining all of those involved in the hurtful messages.

Taschner said in one case, the district has no power — the pumpkin carving happened outside school hours. And in the other case, the investigation into who was responsible for hanging the doll is ongoing, but the district disbanded the boy’s cross-country team for the rest of the season as punishment. Both answers received pushback from an exasperated audience.

But at the heart of last night’s meeting was an even bigger question: How should schools to respond to racist incidents?

The Coatesville Area School District already works to address them through staff trainings with the help of the Mid-Atlantic Equity Center, the NAACP and the Pennsylvania Human Relations Commission. The student body in Coatesville is 51 percent white, 32 percent black and 14 percent Hispanic.

Howard Stevenson, a clinical psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania specializing in race in the classroom, said schools need policies and plans designed to address racism at the student level.

“Policies that can help are, can we have debates on these topics? Part of education is giving people a deeper understanding of why this is happening now,” he said, noting schools can accomplish that by teaching history and fostering debate.

Stevenson said parents and teachers also need a plan for how to talk to their kids and plan for how to act the next time a racial slur is uttered or racially-charged incident occurs.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.