City controller calls for less expensive and faster approach to addressing gun violence in Philadelphia

“The majority of this is not being spent on the type of laser-focused programs that are shown to work,” Rhynhart said. “This is why we thought that transparency was needed.”

File photo: Philadelphia City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart (Lindsay Lazarski/WHY)

This article originally appeared on The Philadelphia Tribune.

—

City Controller Rebecca Rhynhart believes the city can do more to reduce gun violence — and for less money than what it currently spends.

She released a report Thursday that shows the city is spending a total of approximately $15 million on the Youth Violence Reduction Partnership, the Community Crisis Intervention Program, blight remediation and street light upgrades, gunshot detection cameras, payroll for employees of the Office of Violence Prevention, and other grants and programs.

“The majority of this is not being spent on the type of laser-focused programs that are shown to work,” Rhynhart said. “This is why we thought that transparency was needed.”

She said a combination of three programs has worked to reduce gun violence in Chicago, New Orleans and Oakland, and implementing those same programs here in Philadelphia would cost approximately $11 million in the first year and less in subsequent years. “With the city’s cash balances, $11 million per year is doable,” she added.

Rhynhart realizes her role is typically regarded as one focused on accounting, and that her proposal differs from the mayor’s “Roadmap to Safer Communities.”

“Anyone can get mad at me for being in the wrong lane, but you know what? I don’t care,” she said. “People are dying. I’ve stood on the sidelines for two years on this issue while people kept dying and dying. So you know what? I’m going to lean in and do what I can do. And if the mayor gets upset, I can’t control that.”

Mike Dunn, a spokesman for the mayor, said Rhynhart is “stepping into an area she not only knows little about, and has done little research on, save for a report that puts a dollar amount on every homicide as they relate to property values.

“Our violence prevention and reduction teams are working hard every day with actions and programs inherently based in evidence, and successful models that have achieved violence reduction in many big cities across the country,” he continued.

“Addressing the violence is the Kenney Administration’s top priority. Our work is guided by experts in the field who have rich experience with some of the leading names in violence prevention. The Philadelphia Roadmap to Safer Communities is executed by a public health approach, informed by data and research on what works for gun violence prevention.”

Mayor Jim Kenney has committed to slashing the homicide rate by 30% and shootings by 25% in four years.

He introduced his “Roadmap to Safer Communities” at the beginning of 2019. The plan proposes to address gun violence by addressing poverty, and calls for improved workforce development initiatives, reentry programs, prevention and intervention programs, and a public health campaign. The plan also focuses on blight remediation efforts.

The number of homicide victims in 2019 was the highest it has been in 12 years, according to Philadelphia Police Department statistics.

As of 11:59 p.m. on the 22nd day of the year, 32 people were killed in the city, police statistics show. That is 68% more than on the same day in 2019.

Rhynhart believes the city needs to focus more directly on violence than on the types of workforce initiatives and blight remediation efforts spelled out in the mayor’s roadmap. She agreed that many of the things in the mayor’s plan are important, but said they are anti-poverty programs and “the most successful programs are not broad-based anti-poverty programs.”

She said, “We have to focus on the violence.”

Chicago, New Orleans and Oakland have seen significant reductions in gun violence by implementing a combination of group violence intervention (also known as focused deterrence), cure violence (interrupters on the street) and cognitive behavioral therapy programs for young people likely to engage in violent activities.

New Orleans’ program has been credited with a 17% reduction in homicides between 2012 and 2014, and Oakland’s program has been credited with a 32% reduction in gun homicides in five years.

A similar combination of programs in Philadelphia could lead to a 35% reduction in homicides over five years, Rhynhart said.

The city’s poverty rate and homicide rate are intrinsically linked, Rhynhart said, and both are rooted in systemic — and even codified — racism.

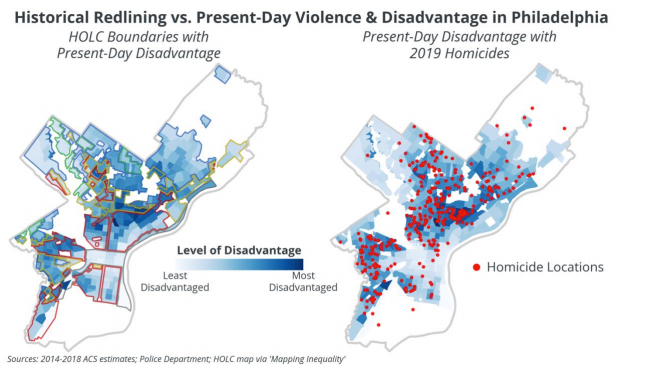

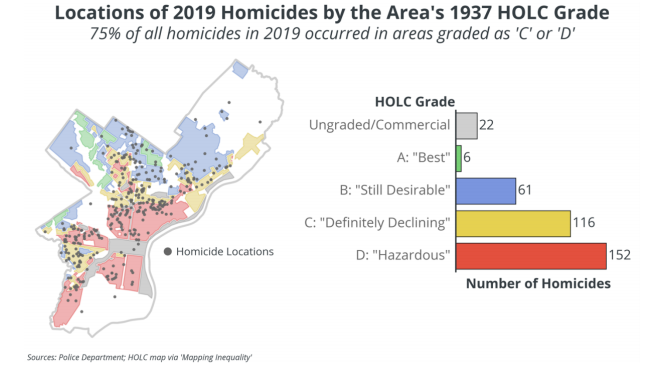

The sections of the city where most of the shootings occurred in 2019 were in areas that were redlined more than 80 years ago — Northwest, North and Southwest Philadelphia.

The federal Homeowners’ Loan Corporation designated those historically Black neighborhoods in the city as “undesirable” areas to lend money for mortgages and business loans, and “set the stage for a lack of investment” in those neighborhoods, Rhynhart said.

“These redlining boundaries are correlated with present-day disadvantage. They basically starved wealth creation from African-American neighborhoods.”

That lack of wealth, particularly contrasted with other parts of the city, depressed poverty values, which led to violence, which depressed property values even further, which led to more violence, and so on.

Society collectively created the problem, Rhynhart said, and “we have a collective responsibility to fix it.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.