Center for Architecture gives awards for urban design psychiatry, ideas for PES site renewal

The Center for Architecture and Design in Philadelphia honors Mindy Fullilove, while pondering how to remediate the PES refinery site.

Protesters with Philly Thrive stood on a pedestrian pathway of the Passyunk Avenue Bridge on June 22, 2020, to demand the South Philadelphia refinery remain closed a year after an explosion at the site. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

This week, the Center for Architecture and Design in Philadelphia will give its annual Edmund Bacon Award to Dr. Mindy Fullillove, a psychiatrist and professor of urban policy and health at the New School in New York.

“It’s a huge honor,” Fullilove said. “Not too many psychiatrists get awards from architecture centers.”

The award is named after the director of Philadelphia’s planning commission from 1949 to 1970. Edmund Bacon had an enormous impact on the layout of Center City, including the way interstate highways 76, 676, and 95 cut through the city’s core. He also wrote a seminal urban planning book, “Design of Cities.”

“Edmund Bacon is an important figure, and somebody I studied in the course of trying to learn about cities when I started to change my research from a focus on diseases and individuals to understanding how social systems work,” said Fullilove. “Bacon’s book was really helpful to me. This is a very meaningful award.”

For decades, Fullilove has been researching urban design and its consequences on mental health, particularly on how urban revitalization developments and disinvestment impact low-income communities. She said the social and economic fallout of the coronavirus pandemic, and the recent protests for racial equity, have highlighted social fractures that make American cities fragile.

“What has made society fragile is a many decades[long] process of undermining the stability of communities, undermining the economy and where people work, and the concentration of wealth,” she said. “Those are the powerful forces that have destabilized our society.”

Her newest book, “Main Street: How a City’s Heart Connects Us All,” is the result of an 11-year study of commercial corridors. She sees main streets as great forms of urban art.

“Main streets have been developed by artists and architects over hundreds of years. That’s a lot of thinking about how to make a space that’s convivial, where you can have good commerce, where you can have civic activity,” she said.

“Of course main streets are under the gun right now with all the businesses that have had so much trouble over the past year, but they are a real source of our heritage of city-building in the United States,” Fullilove added. “I believe main streets are one of the great tools we have as we come back from this pandemic.”

Normally the Bacon award is given during an in-person event at the Center for Architecture and Design in Center City, where the recipient gives a talk. This year it will be virtual. Fullilove will give a talk remotely from her home in New York.

In choosing Fullilove for the award, the selection committee at the Center for Architecture and Design thought about the events of 2020 that have made deep impacts on cities: COVID-19 and Black Lives Matter protests.

“One of the things that came out of the Black Lives Matter movement is the Design as Protest movement, which is a group of architects and designers of color that have led the discussion around how unconscious bias and institutional racism play into our built environment,” said Rebecca Johnson, executive director of the Center of Architecture.

“Dr. Fullilove’s scholarship around mental health, and the intersection of space and cities and how it affects people on a very personal level, is super-relevant and really timely. She’s been doing it for decades. She’s not riding this trend, we are gravitating toward her.”

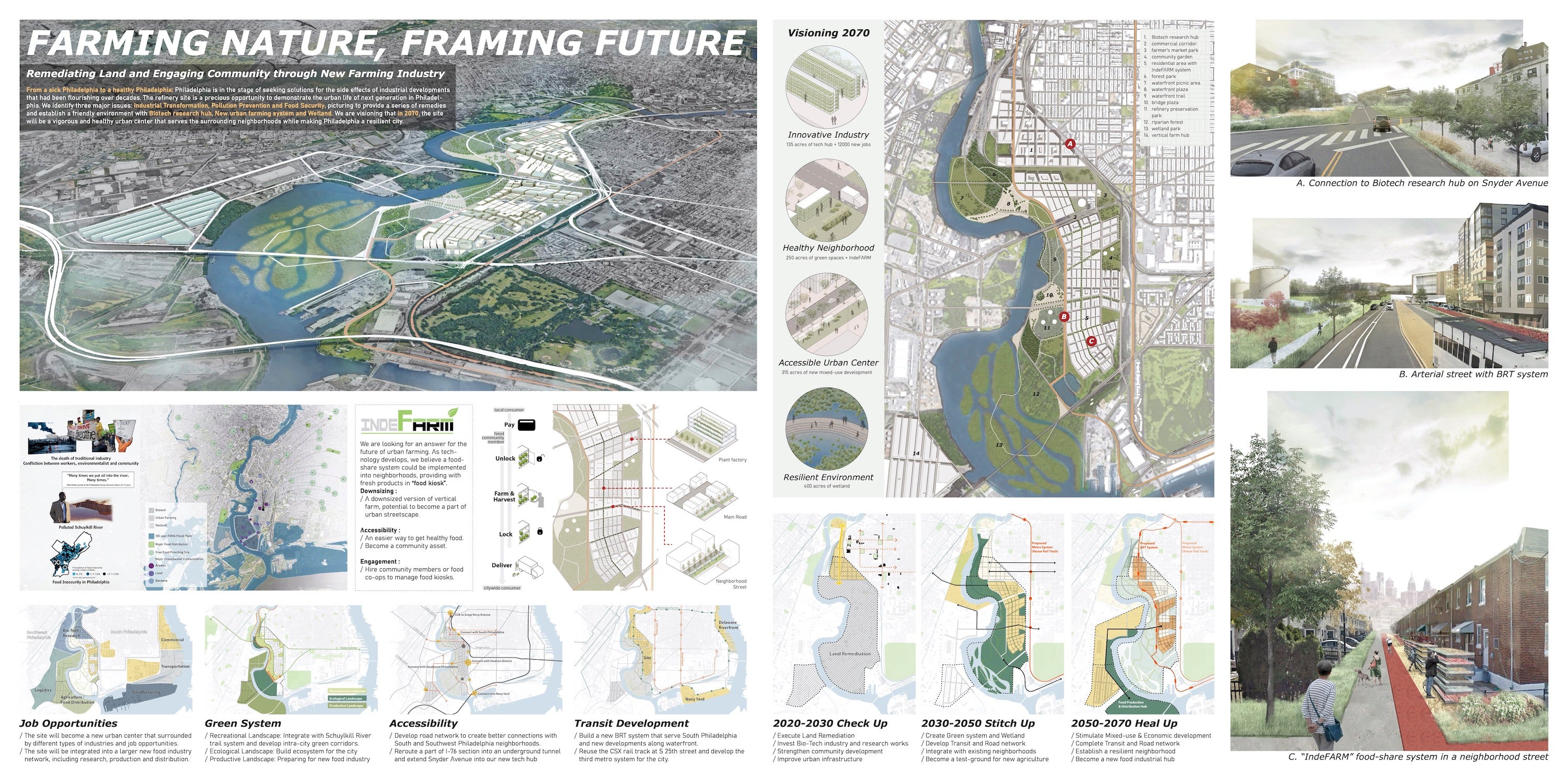

The annual award coincides with a student competition wherein people studying architecture and design around the world devise and submit design solutions for a particular problem or site. This year, the competition asked students to come up with a plan for the former site of Philadelphia Energy Solutions, the refinery in South Philadelphia that exploded almost two years ago.

The PES site, about the same size as Center City, has absorbed the pollution of heavy industry for about 150 years.

“The conversation that’s come out in so many of the student’s projects is about what’s a realistic, and yet creative, way forward,” Johnson said. “This is such a big site, it would be really expensive to clean it up 100%. That’s not a realistic expectation. There needs to be a considered and intentional planning around the community that has largely suffered the negative health impacts of this site.”

The design competition is not tied to any development decisions that will be made regarding the PES site, and none of the submissions will likely have a direct impact on how the property is remediated. The competition is about innovative ideas, so students were encouraged to be ambitiously creative.

Most of the students went far beyond the boundaries of the PES site, proposing ideas about environmental and community sustainability stretching north along the Schuylkill River up to Grays Ferry and east into South Philadelphia.

Like many of the proposals, a team of graduate students at the University of Pennsylvania proposed to flood the southern part of the PES site, allowing the Schuylkill to take back the lowland real estate.

“It’s in the flood zone. That’s why we think it’s better to give it back to nature,” said Shaoan Chiu, part of the team of four Penn Design students who won the competition. “Bring more natural environments into our site, for ecological and recreation uses.”

That plan imagines the parcel of land across the river now populated by giant oil tanks being converted into vertical farms, and developing the northern part of the PES property into a biotechnology research hub.

Chiu said the plan would leverage the existing assets of that part of the city.

“This site has a deep relationship with the South Philadelphia neighborhood, and it’s close to Southwest Philadelphia where they have a logistics industry and a fresh wholesale market,” he said. “We were thinking about how we integrate these diverse programs into a hub as a new urban center for Philadelphia.”

The proposal imagines overlapping infrastructures of transportation, employment opportunities, food distribution, and synergies of biotech research of agricultural commerce integrating into the plan.

The first runner-up submission, by Sam Emory of Temple University, imagined the remediation of the PES site could result in an engineered soil plant, creating soils designed for specific applications such as stormwater management and erosion control.

The second runner-up, by a team from Leeds Beckett University in England, is a plan to establish a roster of “Community Institutes” who would act collectively to plan a redevelopment strategy.

“We propose regeneration led by Philadelphia’s communities, supported by its technical institutions,” reads the proposal. “By engaging with people or groups that are fighting against the same problem, their interest, capacity, and influence can be grown through partnering with an established academic, technical, social or research establishment.”

All of the competition submissions will be displayed publicly next fall, during the annual DesignPhiladelphia festival.

Normally, the Edmund Bacon Award recipient and the student competition have little to do with one another. They are usually two distinct programs of the Center for Architecture that culminate at the same time. Johnson said this year the two are unintentionally related.

“The PES site is an area larger than Center City. It’s a huge opportunity to make a positive impact,” Johnson said. “For years it’s had an economic impact, but not such a great health and community impact.”

Fullilove said the PES site can be thought of as an analogy for the larger problem of how American society recovers from the economic, political, and social damage of the pandemic.

“There’s a lot of pollution on that site — a lot of ways we have injured the land. You can’t do anything with the land until you remediate it,” Fullilove said. “If we think about it by analogy – do we have remediation tasks? That’s very helpful for the imagination. We do have remediation tasks.”

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.