Center City has more parking permits than parking spaces, and other fun parking findings

Center City resident William West has been busy the past few months collecting information from the Philadelphia Parking Authority about the on-street parking system and blogging the results at his site West Words, and I want to boost the signal on some of his findings as they have important significance for some of the live policy debates regarding parking.

West started submitting Right-to-Know requests to the PPA because he noticed that on-street parking revenues are all lumped together as a single category in PPA’s financial reports. Of course, those revenues actually come from a variety of sources like tickets, meters, and residential permits, and the exact breakdown tells us a lot about how the PPA and the city think about managing parking and street space. Here are a few facts to chew over.

On-street parking revenues account for a little over half of all PPA operating revenues

According to the most recent financial statements, which take us up through March 2014, about $122 million of PPA’s roughly $234 million in operating revenue comes from on-street sources. The rest of the revenue comes primarily from they 24,869 off-street airport parking and Center City garage parking spaces they own or manage.

PPA collects more revenue from tickets than parking meters

About 62% of PPA’s on-street parking revenue comes from tickets, and about 28% comes from parking meters.

The remaining 10% comes from a plethora of fees and contracts, the largest of which are towing (3%), booting (1.5%), credit card fees (1%), and residential parking permits (0.8%).

West points out that in San Francisco, where they’ve been trying out a demand pricing strategy for parking called SF Park, that ratio is flipped. Curb meters bring in twice as much money as tickets, and in some areas it’s even more.

“At the end of the SFpark demonstration project in 2013, the pilot areas were collecting four dollars in meter revenue for every dollar of parking fines,” he writes.

This isn’t an exact apples-to-apples comparison for a variety of reasons West mentions, but the basic difference in approach is still clear: San Francisco relies more on revenue from metering curb parking, and Philly relies more on revenue from tickets. West thinks our fine-heavy system is a reaction to the political difficulty of installing more curb meters or increasing meter rates:

And I think our ratio says a lot about us, here in Philadelphia. There is intense resistance to adding new meters, or raising the rates on existing ones. The inevitable result is overcrowding, which leads directly to a large revenue stream from parking tickets. Along with the overcrowding and the tickets we also produce a lot of anxiety, frustration, and anger. Parking is a very emotional issue in Philadelphia, and few of those emotions are positive.

Parking permit and loading zone prices are totally arbitrary

City Council created a stepped pricing schedule for residential parking permits last year, and the permits now start at $35 a year, getting more expensive with each additional car, up to $100 apiece for the fourth vehicle and beyond. A permanent loading zone costs a bit more annually, though still just $150, with a one-time $500 installation fee.

But Richard Dickson, deputy Executive Director of the PPA, told CBS at the time that these fees still “don’t come close” to recouping the permit program’s operating costs.

The Parking Authority only brings in $1,059,648 from residential parking permits each year, $1,062,525 from contractor parking permits, and $468,705 from loading zone fees. In total, that’s about 2% of on-street revenues.

We don’t have a breakdown yet for the operating costs of the permit system alone, but the operating costs for the whole on-street parking system are about $60 million, and the administrative costs are about $12 million (almost 60% of on-street revenues in total.) Point being, long-term curb parking revenues are just a drop in the bucket, and people parking long-term on the curb are receiving a fairly significant subsidy.

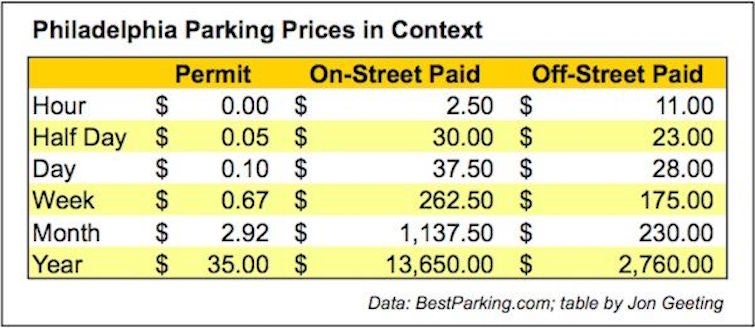

What would unsubsidized parking actually cost? When I looked at the costs of private off-street parking facilities for Next City, the median price turned out to be about $2,700 a year for a space in a parking lot or garage in greater Center City. Alternatively, if we arrive at an annual cost using PPA’s current hourly meter rates, that would be $13,650.00 a year. No matter how you slice it, the going rate is many times more than $35.

Here’s a chart comparing the different rates. What should be clear is that the prices being charged for longer-term curb parking are politically-derived and don’t have any relationship to the going rate for parking spaces.

The number of parking permits is totally arbitrary

Parking permit Zone 1 covers two RCO territories, Center City Residents Association (CCRA), and South of South Neighbors Association (SOSNA), and has 6,957 parking permits currently active.

CCRA and SOSNA recently completed inventories of the curb parking spaces within their boundaries. CCRA counted 1,584 Zone 1 spaces, and SOSNA counted 2,103, totalling 3,687 Zone 1 spaces.

That means there are roughly two curb parking permits for every curb parking space in Zone 1. West’s theory is that many of the permit holders also have off-street residential parking, but buy the permits because they’re so cheap, so the daily unmet demand for parking is somewhat less intense than that upside-down ratio suggests.

SOSNA is pushing a proposal to split Zone 1 into two zones, to free up some curb parking in the neighborhood that’s currently used by residents from Center City storing their cars south of South Street.

West got the breakdown from the PPA and found that if this proposal comes to pass, CCRA will have about 2000 more active permits than spaces, and SOSNA will have about 1000 more permits than parking spaces.

SOSNA has 2,781 spaces though that are either uncontrolled or have a two-hour limit, so there’s some room to manage the parking crunch by opening up more blocks to zoned parking.

Stepping back to look at the big picture, these numbers raise some important questions about how we manage space on the streets that probably deserve to be debated anew in the next administration in light of declining car use in Philadelphia and all across the region.

What we have essentially is a pricing system that favors on-street parking over off-street parking, long-term curb parking over short-term curb parking, and prints parking permits on autopilot, unconstrained by the actual number of curb spaces. That’s a recipe for a curb parking crunch, and it goes a long way toward explaining Philly’s bitter parking politics.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.