Center City District report highlights transit as competitive necessity for region’s economy

If everyone drove to work in Center City, how much parking would we need?

According to a new report from the Center City District: 2.6 square miles of surface parking. The size of William Penn’s 1682 plan for the city? 2.2 miles.

Visualize that another way: If you were to build parking garages the size of the Comcast Center, you’d need 28 of them.

If everyone drove to work in Philly, parking spaces would crowd out the actual places of employment. In other words: Transit matters.

That’s the takeaway from Center City District’s latest report, which examined where the region works and how people commute.

Over the past few years, Philadelphia has been growing and Center City has led the way. Jobs in Center City grew 5 percent between 2010 and 2014, and residents increased 7.9 percent. At the same time, though, Center City lost parking: more than 3,000 spaces. Yet, at the same time, parking availability actually increased. The ineluctable conclusion: More Philadelphians are walking, biking and taking transit to work than ever before.

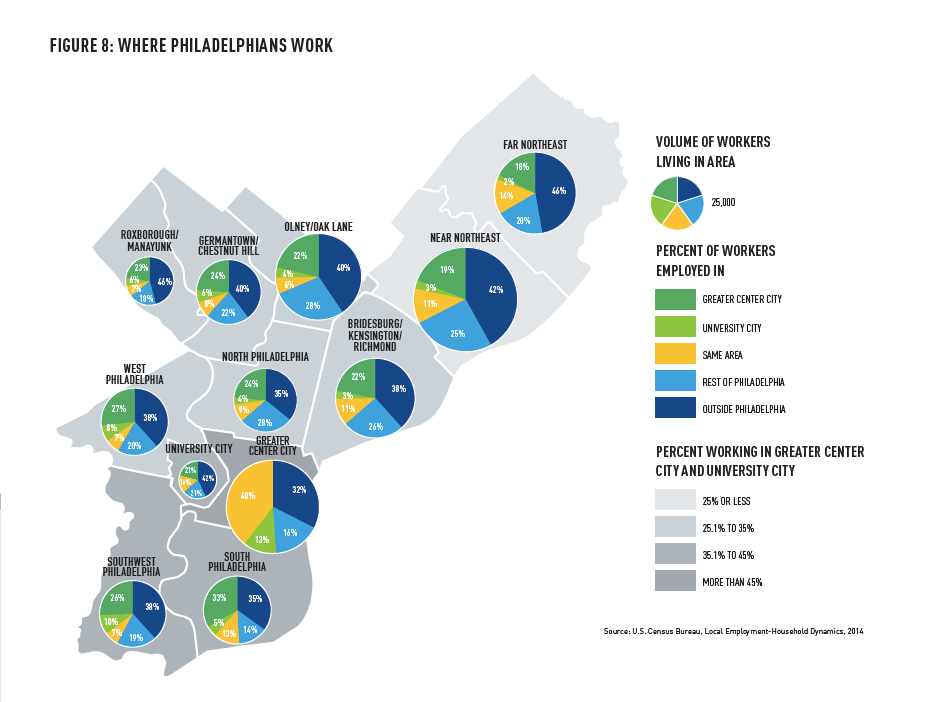

Center City workplaces employ 295,000 people, accounting for 42 percent of all Philadelphia’s jobs, and University City accounts for another 12 percent. While 40 percent of Greater Center City residents also work in the district, residents make up just 10 percent of Center City work force. Everyone else commutes, either by train, bus, bike, car, or foot; 41 percent come from elsewhere in Philly, 39 percent from the metro area suburbs, and a final 10 from further out still.

The reason why Center City and University City are Philly’s job hubs is simple. Jobs beget jobs. That was the lesson Lori Reiner offered in a presentation accompanying the report’s release Tuesday, wherein the accounting executive explained why her firm recently relocated to Center City. Reiner, who runs EisnerAmper’s Philadelphia office, said her firm decided to relocate from Jenkintown in 2014 to better connect with clients and their own vendors. In Center City, there are 203 jobs per acre. Outside the city, there are only 0.6 jobs per acre. Job density leads to the fortuitous meetings and serendipitous chance encounters that drive innovations and collaborations in today’s economy, said Center City District Executive Director Paul Levy, who presented the report’s findings.

Jobs don’t just beget more jobs. They beget residents. Reiner estimated that the number of her employees living in the city has doubled since the move. Reiner reported that the Philadelphia branch was growing, both in workforce and business, and that the employees overwhelmingly supported the move. It helps that EisnerAmper covered Philadelphia’s 3.9 percent wage tax for all their employees who made the move, increasing salaries to “make them whole.”

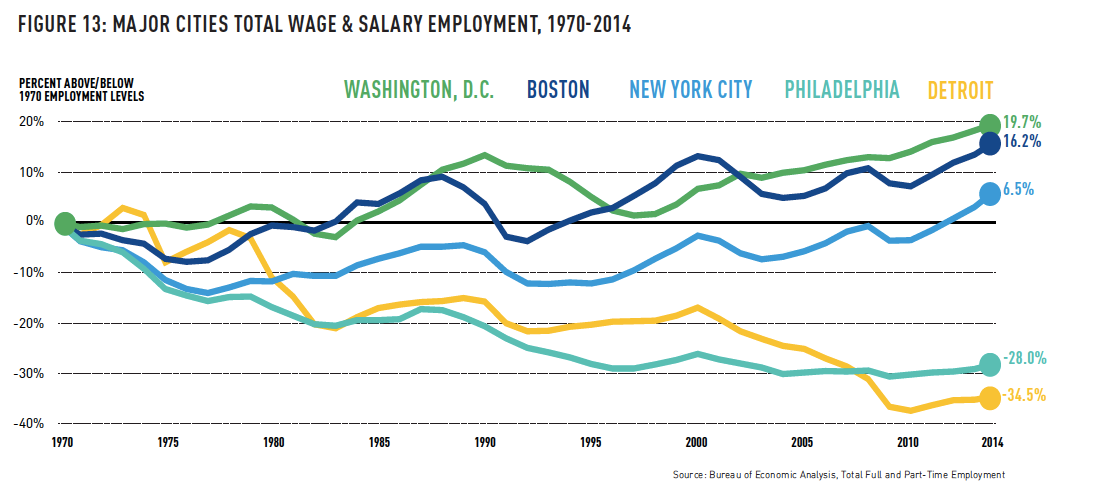

Wage-tax reform has long been an interest of Paul Levy, to better incentivize the kind of job and resident growth that EisnerAmper exemplifies. Levy argues that the city foolishly taxes something that’s highly mobile—jobs—instead of assessing levies against more-stationary objects—like real estate—which explains Philadelphia’s anemic job market. On Monday, the Pennsylvania House approved a bill that would amend the state’s Uniformity Clause, which has prevented Philadelphia and other cities from taxes different types of real estate at different rates. If the bill also passes the Senate, Philadelphia could impose higher property taxes on businesses, and allow the city to simultaneously reduce the wage tax. It’s a plan Levy has pushed for years, building a coalition of business leaders around him.

Philadelphia is blessed by good transit infrastructure, said Levy, and it makes more economic sense to move jobs to transit-accessible locations than make remote locations more transit accessible.

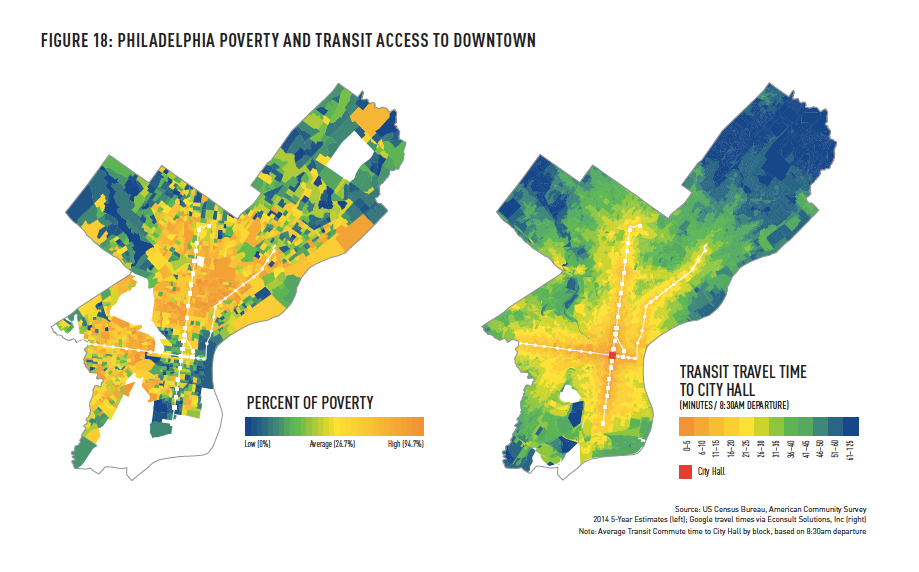

That doesn’t just make sense from a pure societal cost basis. It’s also much more equitable for Philly’s lower income residents. The city’s poorest neighborhoods are concentrated in West Philadelphia, North Philadelphia, and the Lower Northeast. But all of those areas are well served by SEPTA’s Market-Frankford and Broad Street Lines.

The report doesn’t offer a ton of new statistics, repeating plenty of the facts and figures found in the State of Center City report released earlier this year. Still, the context matters, and some of the findings bear repeating.

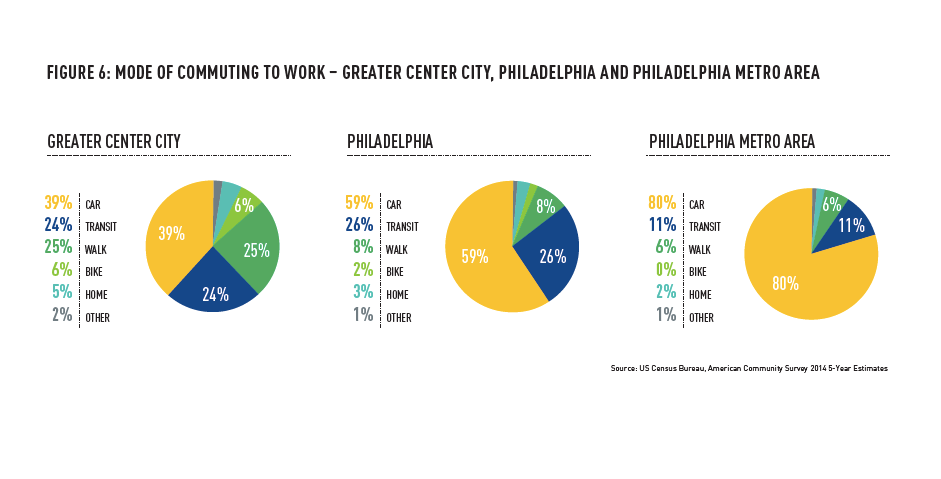

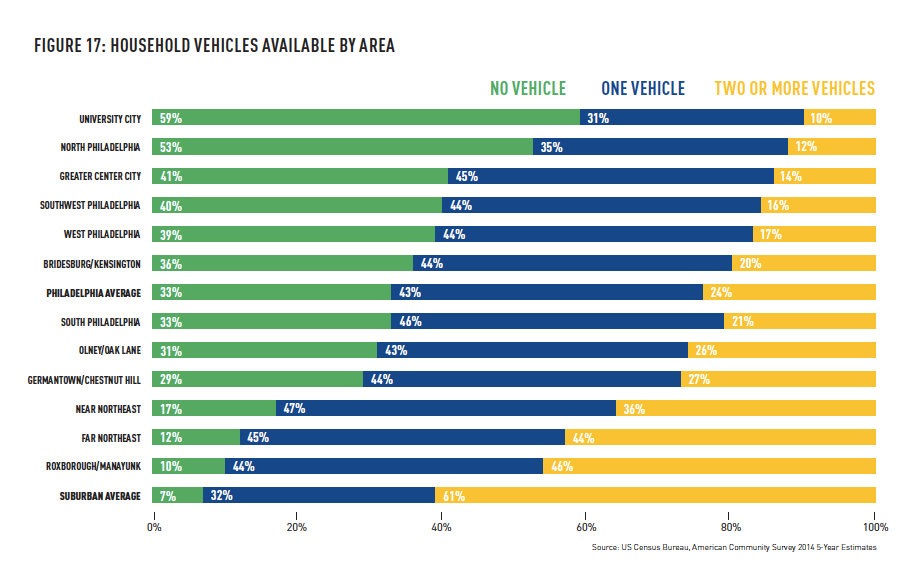

For example, in Greater Center City, just 39 percent of residents commute via car. In Philadelphia as a whole, that number goes up to 59 percent. In the entire metro area, it’s 80 percent. The city neighborhoods where it’s easiest to get by without a car are a geographic and economic mix, meaning that relocating more regional jobs to the city’s downtown areas would benefit Philadelphians of all classes.

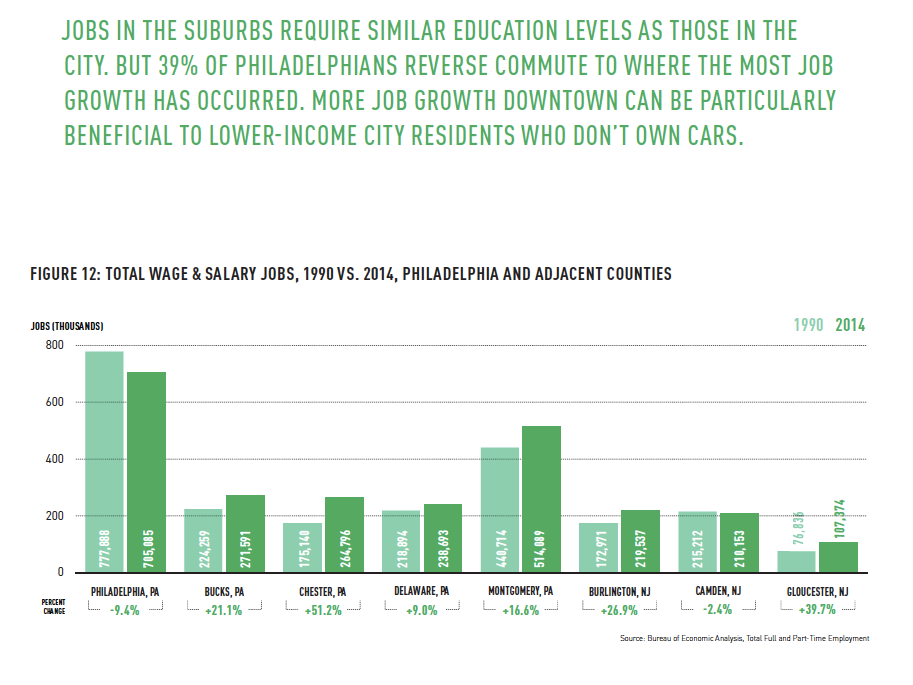

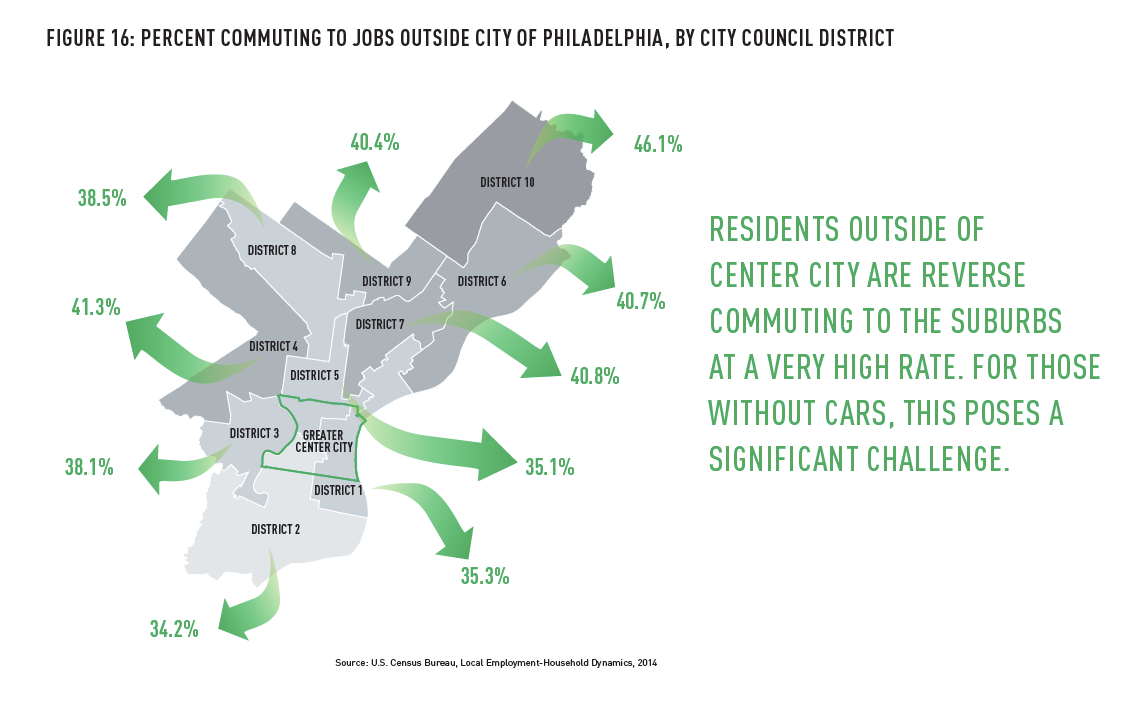

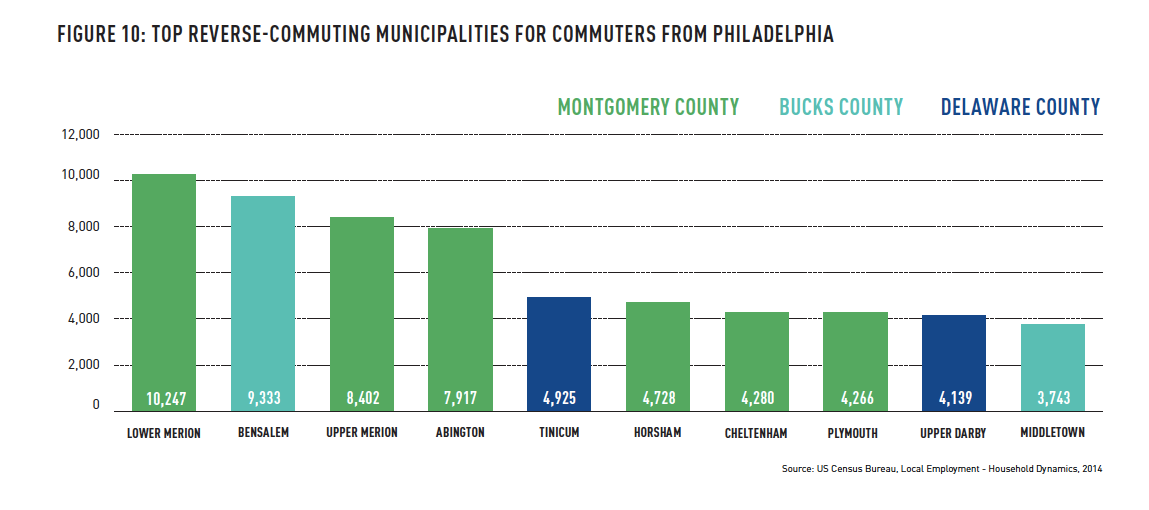

The report also highlights the numbers of Philadelphians who reverse commute. Directly adjacent Lower Merion and Bensalem nab the number one and two spots respectively, but right behind them is Upper Merion, driven by the King of Prussia mall, which has nearly three-quarters as many retail jobs as Greater Center City. Those jobs pay an average of $25,000, says the report, but unless and until SEPTA builds it’s extension of the Norristown High Speed Line, many mall employees are stuck with long commutes relying on multiple bus transfers. Those that are lucky enough to have access to a car—only half of lower income city households have access to automobiles, says the report—still have to pay the annual average of $8,500 to operate a car, according to AAA estimates.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.