Can your well water make you sick? No testing is required in Pennsylvania.

Shirley and Bob Redcay, of Denver, were sure their home was getting clean drinking water from the brand-new well on their property.

Jerry Solomon, of West Lampeter Township, rolls the stone slab that covers his private well water pump at the back of his home on Dec. 9, 2019. (Brett Sholtis/Transforming Health)

This article originally appeared on StateImpact PA.

Shirley and Bob Redcay, of Denver, were sure their home was getting clean drinking water from the brand-new well on their property.

The couple built the home about three years ago just before they relocated from Florida.

But, after reading a story in LNP|LancasterOnline in September, they realized private well water is not regulated in the state — their water was never tested. Worried about possible health concerns, the couple immediately called a local company to have their drinking water tested.

The couple isn’t alone in their concern about water quality. Medical professionals, scientists and drinking water experts say the condition of drinking water is a significant factor in a community’s overall health.

Legal limits for contaminants in drinking water, such as lead and bacteria, are only enforced in public water systems — systems that serve 25 people at least 60 days out of the year. The state and federal government both monitor public drinking water to ensure contamination stays below established limits.

Pennsylvania’s one million private wells are not monitored by any government agency and no maximum contaminant levels are enforced for private systems. There are 38,000 private wells in Lancaster County alone.

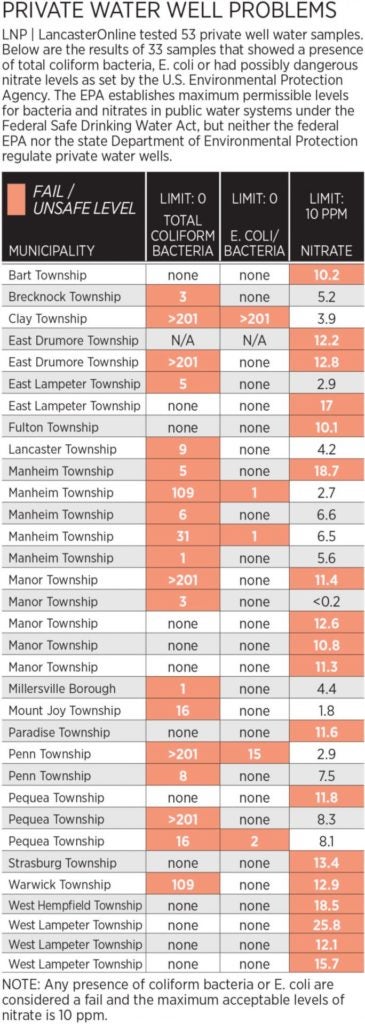

An LNP|LancasterOnline analysis found that of 53 water samples taken throughout Lancaster County, about 62% (33 samples) had at least one fail — either a presence of bacteria was detected or nitrates were above the 10 parts-per-million standard established by the Environmental Protection Agency for public drinking water systems.

However, according to experts, the maximum legal limits for how much of a contaminant can be in a drinking water source doesn’t always mean that water is healthy to drink. And nitrates are the perfect example.

What levels are safe?

According to an EPA spokesperson, in the agency’s most recent review of drinking water standards, published in 2017, the agency determined it was not appropriate to revise the existing nitrate maximum contaminant level.

“Consistent with implementing the Safe Drinking Water Act, EPA will continue to monitor research on nitrates and other drinking water contaminants and will determine the next steps as appropriate in future reviews of drinking water standards,” the EPA’s statement said.

The greatest use of nitrates, according to the EPA, is as a fertilizer.

The nitrate standard of 10ppm was set in the 1960s based on methemoglobinemia, or blue-baby syndrome, said Sydney Evans, science analyst with the Environmental Working Group (EWG), an environmental health research organization.

The condition occurs when nitrates block the body’s ability to carry enough oxygen to cells throughout the body, resulting in the person appearing blue. The toxicity is especially dangerous for infants and pregnant or breast-feeding women.

According to a Pennsylvania Department of Health spokesperson, blue-baby syndrome is not a reportable condition and never has been. Therefore, there are no official numbers for how many cases, if any, occur statewide.

Since the 1960s, research has shown that even at levels lower than the current EPA maximum limit for nitrates, there are higher risks of birth defects and an elevated risk of cancer, Evans said.

A 2019 research assessment of nitrates in drinking water found that 2,300 to 12,594 national cancer cases can be attributed to nitrates and those cases can incur medical and indirect costs between $1.5 and $6.5 billion.

Evans and her fellow assessment authors recommended that the legal limit for nitrates in drinking water be lowered from 10ppm to 1ppm.

“What EWG really wants is for those legal limits to be re-visited and re-reviewed in light of that latest data,” Evans said. “Because that’s not what the current legal limit is based off of, the current legal limit is not health protective.”

Health risks

Low contaminant levels in water may not be an immediate risk to a homeowner’s health, but over time, they can cause problems, said Peterson.

When something occurs slowly over decades, it’s hard for people to put it on their high priority list, he said.

“But obviously, if you’re ingesting, for example, nitrates in your water supply every day for years, this is going to be something that will show up later,” Peterson said.

The problem is, it’s hard for physicians to trace an ailment to contamination in a patient’s water — especially if the contamination has been gradual.

“Unless you produce yourself to the doctor’s office with bloody diarrhea and the doctor or the patient said, ‘hey, can this be E. Coli infection?’ it’s not always that easy to diagnose these things,” he said.

Like radon, as more research comes out about contaminants in water, Peterson believes that science will move towards saying there are no safe levels of contamination.

“If it was my water, I wouldn’t be drinking it if there were over 5 parts (of nitrates) in it,” Peterson said.

Remedies

When the Redcays built their first home in Florida 25 years ago, the well on their property was tested in accordance with state law before they moved in, the couple said. Presuming Pennsylvania law was the same, the couple drank the water at their current home without concern.

Once they learned their well water was never tested, the Redcays contacted a local company to test the water.

After testing, the company sent them a letter. “The Bacteriological test indicated the PRESENCE OF COLIFORM BACTERIA in the water as sample. Therefore the water, as tested, is NOT OF SANITARY QUALITY.” The letter advised them not to drink or cook with the water until “corrective measures” were taken, but the letter did not offer further information

Confused and frustrated, the Redcays decided to wait and get another test. In the meantime, they continued to drink their water.

Confused and frustrated, the Redcays decided to wait and get another test. In the meantime, they continued to drink their water.

The Redcays are not alone in their uncertainty about how to proceed with their water dilemma.

Jennifer Fetter, a Penn State Extension educator, says she often gets these types of questions from well owners.

“My message to somebody who has a high level of any human health contaminant, whether it’s really high nitrates or really high bacteria, is you really need to get some quotes and get some folks in to talk to you about treatment systems,” said Fetter. “And in the meantime, seek an alternative water supply for your family.”

Anyone who has a compromised immune system, children, pregnant or breastfeeding women should be provided with an alternative water supply until a water treatment system is in place, she said.

However, people with contaminant levels that are just above EPA standards should not panic, Fetter said.

“The EPA standards are what they are for a reason,” she said. “They’re not meant to cause alarm the second you go over the standard – that’s just the point at which you should now be treating and reducing. It’s really numbers that are higher than that that tend to cause the health problems.”

Although testing in January showed a small presence of total coliform bacteria in their water – and negative for E. coli, the Redcays now feel more equipped to move forward.

And clean groundwater isn’t just a single home owner’s concern, said Allyson Gibson, coordinator for the Lancaster Clean Water Partners, an organization comprised of various regional groups concerned about water issues.

“Clean water, public health, and quality of life depend on each other, and that translates to a need for collaboration in Lancaster County,” Gibson said in a statement. “Neighbors and community partners need to work together on restoration projects that improve our local waterways.

The Redcays confirmed that their water does have a small presence of total coliform bacteria when they decided to have their water tested through LNP|LancasterOnline in January.

“Now that we do know, we’re looking into a solution,” said Bob Redcay.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.