Building a City of the Dead

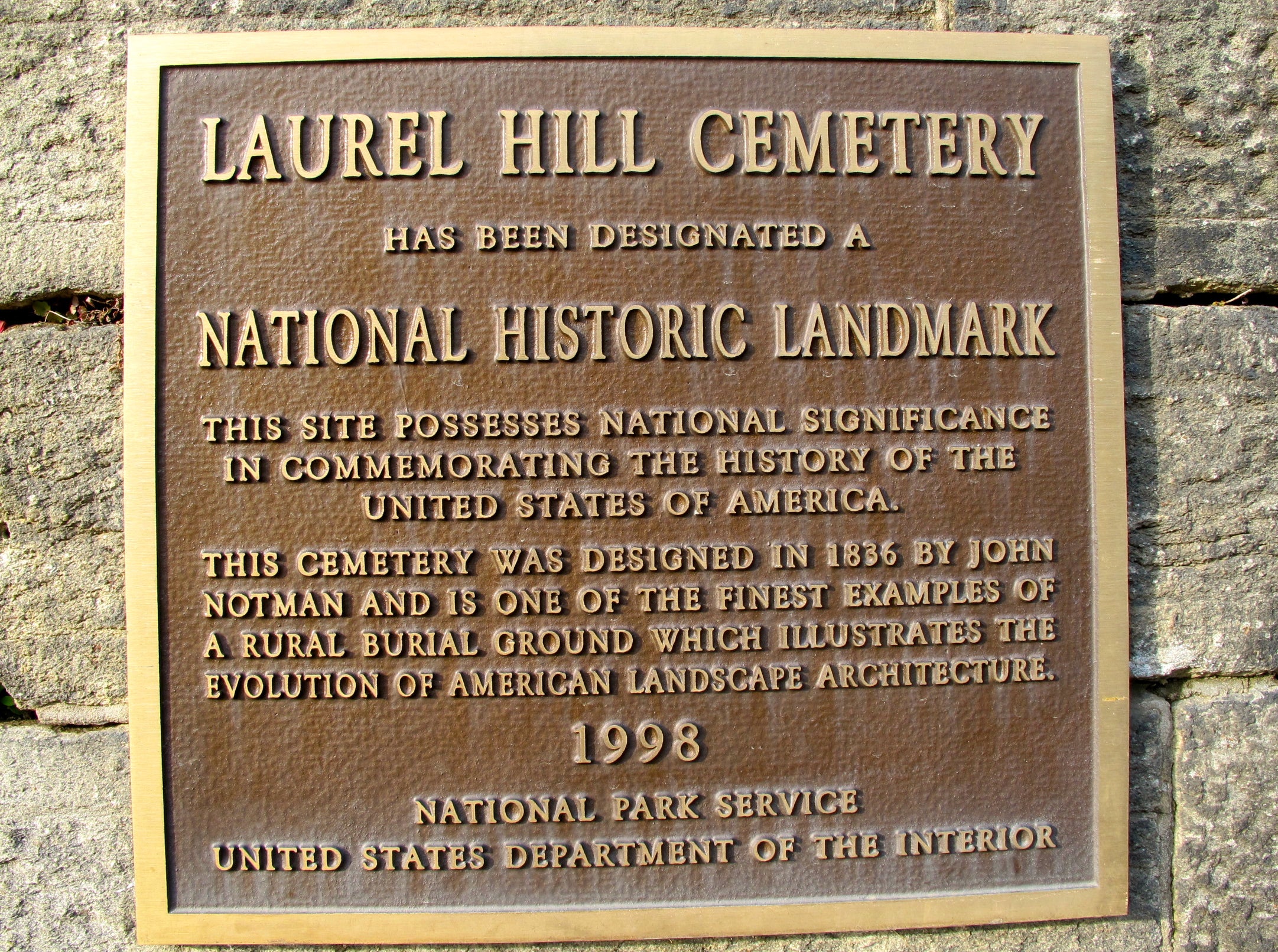

During its heyday, it was one of the most densely populated swaths of land in Philadelphia. Some 70,000 souls called it home — permanently. Founded in 1836, as the city’s first “rural” cemetery, Laurel Hill has served over the decades as both a “scene of development — and a possible antidote to it,” to quote from a new exhibit at the Library Company of Philadelphia. The exhibit, presented jointly with Friends of Laurel Hill, was guest curated by Aaron Wunsch, a lecturer at the University of Pennsylvania Design’s graduate program in historic preservation.

On view through April of next year, “Building a City of the Dead: The Creation and Expansion of Philadelphia’s Laurel Hill Cemetery” presents the story of our most celebrated resting place. A trove of maps, books, lithographs, and ephemera — much from the Library Company’s own collection, some from the neighboring Historical Society of Pennsylvania, as well as other local institutions — lays out the complex missions and expectations embodied in this new kind of burial ground. It’s a fascinating look at a place that, created for one purpose — the interment and subsequent mourning of the dead — quickly grew into something much more significant.

The sprawling hillside site began simply enough, as an alternative to a city rapidly becoming crowded with both the dead and the living. Until the early 19th-century, wealthy Philadelphians ended up in somber graveyards affiliated with churches, while the poor and the criminal were buried anonymously, in potters’ fields. A rising middle class found eternal peace in “associate” or “social” cemeteries. As each of these spaces filled to capacity, though, a new movement surged in big cities around the world: the idea of the extramural, naturalistic cemetery.

In the late 18th-century, Pere Lachaise in Paris was developed as a premier example of this trend. It wasn’t until 1831 that a similar cemetery opened in the United States, Massachusetts’ Mt. Auburn, located in Cambridge just outside of the teeming city of Boston. Plans for both cemeteries are on view at the Library Company exhibit.

Mt. Auburn wasn’t just any cemetery — in fact, today it is widely hailed as America’s first example of a large landscaped public space. Former Philadelphia Mayor, Benjamin Richards, knew this as did an ordinary citizen, John Jay Smith. In fact, so frustrated was Smith by a futile attempt to locate the grave of his daughter at the overcrowded Friends Western Burial Ground at 16th and Cherry streets, that he decided to bring the idea to Philadelphia.

The city’s “living population has multiplied beyond the means of accommodation for the dead,” he declared. The two men recruited others and the resulting team set about trying to find a properly rural site, scouting along the Schuylkill River, in particular. They rejected those too near the city or not picturesque enough, before settling on Laurel Hill, which was available for sale and offered dramatic bluffs and unparalleled views.

Through architectural drawings by designers like Thomas Ustick Walter (Girard College, Andalusia) and William Strickland (Second Bank of the U.S., Merchants’ Exchange, National Mechanic’s Bank) early in 1836, the exhibit showcases proposed layouts and architectural elements, some of which appear in the ultimate plan. For that, the team chose John Notman, a Scottish emigre who identified himself primarily as a carpenter.

Things moved quickly. The cemetery received its first burial in October of 1836, and within three years, nearly half of its original 800 plots were claimed. Soon, an expansion was called for and since the adjacent land was unavailable, a separate annex was established to the south. In the mid-1860s, the two parcels were joined.

An indisputably popular place to rest eternally, Laurel Hills — and other rural cemeteries such as Philadelphia’s Woodlands, which entered the picture in 1840 —also held tremendous appeal for those who were very much alive. The pastoral surroundings and splendid vistas, it was soon discovered, made for great promenades, picnics . . . and paintings. One oil, on loan from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art, portrays the cemetery’s grand portico in a swirl of golden light and dreamy mist, a veritable arcadia. A nearby vitrine holds lithographs, photographs, and sketches depicting similarly serene settings.

It wasn’t long before the idea of using rural cemeteries like Laurel Hills as pleasure grounds created turmoil, and the management instituted new ground rules to control crowds and maintain a peaceful environment, even going so far as to issue tickets.

The tourism industry was not the only one to benefit from the development of Laurel Hill. A booming industry catering to the grieving also evolved. The exhibit offers a cadre of sales books and illustrations that feature the storefronts and advertising blandishments of the iron forgers, mantle sellers, outdoor furniture purveyors, marble workers, stone cutters, nurserymen, undertakers, and coffin warehouses which set up shop in Spring Garden and elsewhere.

There were even odd inventions, like the piece designed by the aptly-named John Gravenstine that occupies center stage in the exhibit’s main room. A mahogany contraption set on wheels, the “Corpse-Preserving Casket” (ca. 1871), is essentially an icebox placed on top of a coffin. It’s quite the fascinating artifact, an ungainly melding of several cutting-edge technologies, including mobile refrigeration and airtight coffins.

The exhibit finishes with a look at the Victorian culture of mourning (curated in-house by Cornelia King) which, due to the preponderance of early childhood deaths, could easily skew toward the maudlin. (Think: Dickens.) A whole body of work — called consolation literature here — evolved, with one such 1852 book on display typical of its genre. Titled “The Mourner’s Friend or Sighs of Sympathy for Those Who Sorrow.” it sports an illustration of a naturalistic cemetery setting — Laurel Hill.

Another such guide, “A Friendly Visit to the House of Mourning” (1848), includes a binding rich in symbolism, the exhibit points out. It shows a woman in a setting evocative of the rural cemetery, with trees, a broken column (understood to suggest a life prematurely cut short), an obelisk, and a mausoleum.

Gradually, the glory days of rural cemeteries waned, as they at once became more prevalent — in 1856, Mount Vernon Cemetery opened right across the street from Laurel Hill — and true urban parks like Fairmount Park blossomed.

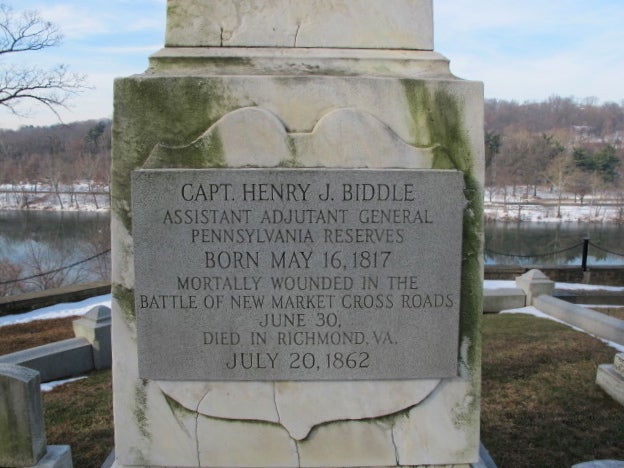

Today, architecture fans, cemetery buffs, history seekers (more than 40 Civil War-era generals and a half dozen Titanic victims/survivors are buried here), and the occasional general tourist make pilgrimages to Laurel Hill. Hey: There’s even the “tombstone” of “Adrian Balboa”, a movie prop that still holds pride of place near the entrance.

Certainly, every Philadelphian should visit, as well.

But this beautiful refuge, and National Historic Landmark, isn’t really on that many radar screens anymore. Perhaps the Library Company’s exhibit will help rectify that.

Contact the reporter at jgreco@planphilly.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.