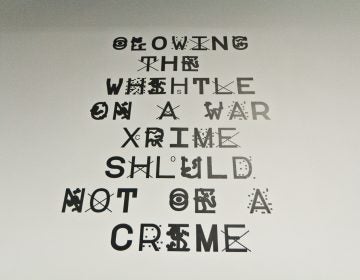

Birth of cool: 40-year retrospective of Dieter Rams’ product design at Philly art museum

If you’ve ever tried to imagine what a space-age bachelor pad might look like, this exhibition of his stereo equipment and modular furniture may come close.

-

German designer Dieter Rams speaks at about the exhibition surveying his career at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Two radios illustrate the impact of the Ulm School on Braun's products. The first (left) was designed in 1954 by Braun AG, and the other in 1956 by Dieter Rams and the Ulm School of Design. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

As Braun's chief design officer, Dieter Rams oversaw product design for an enormous range of goods. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

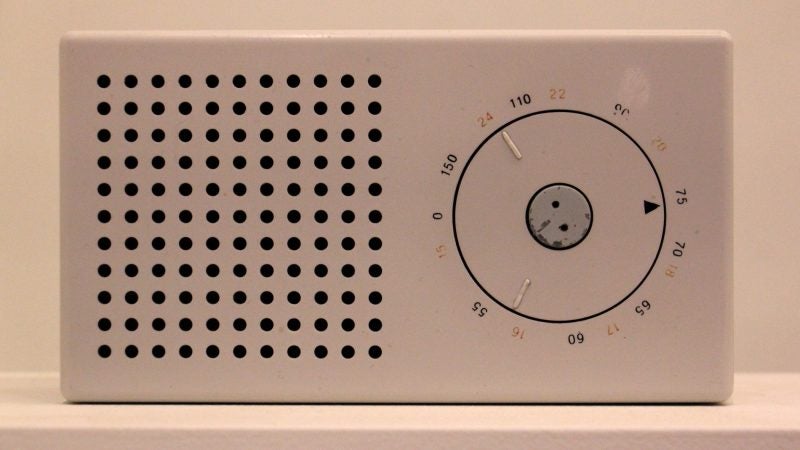

Apple designer Jonathan Ive's design for the iPod echoes the geometeric logic of Dieter Rams's TP 1 radio (shown), designed in 1958. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Dieter Rams designed the Universal Shelving System made by Vitsoe, which has been in continuous production since 1960. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Dieter Rams designed this combination phonograph and radio in 1956, one of the most iconic designs of his early career. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Apple designer Jonathan Ive's design for the iPod echoes the geometeric logic of Dieter Rams's T3 radio. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Dieter Rams believes all the things in your home – the furniture, the appliances, the stereo – should behave like an English butler: there when you need them, fading away when you don’t. He came out of the design ideology of the Bauhaus school that less is more.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art is honoring Rams with a retrospective of his product designs, “Dieter Rams: Principled Design,” and its annual design excellence award presented by Collab, the museum’s design group.

He is also the subject of a new documentary, “Rams” by Gary Hustwit, screening on Nov. 28 at the International House at the University of Pennsylvania, in partnership with the Art Museum.

Rams started in the 1950s, designing transistor radios for the German company Braun, making them in molded white plastic with no ornamentation and as few knobs as possible. More than 40 years later, Apple based the design of the first iPod on Rams’ radio.

In the 2000s, after retiring from Braun, Rams was one of the few outsiders invited by Apple’s designer Jony Ive into his top-secret lab in Cupertino, California.

“The first thing I said when I came in was, ‘I feel at home,’ ” said Rams of that experience. “The atmosphere and everything was family to me, like it was my own department.”

Functional sights, sounds

If you’ve ever tried to imagine what a space-age bachelor pad might look like, this exhibition of his stereo equipment and modular furniture may come close. Rams pioneered the use of plastic and aluminum in housewares, using curved surfaces and clean lines that express only functionality.

The style is not just aesthetic. As a fan of early bebop jazz (he used go out to watch Americans as they toured through the “jazz cellars” of Europe), Rams did not like speaker cabinets faced with woven textile. The music sounded as if it were muffled under carpets. In the 1960s, he designed speakers with perforated metal screens to deliver sound that was crisper, more present.

One of Rams’ most iconic stereo systems was the SK-4, a turntable and radio in one unit. He designed the body with wood and aluminum, then topped it with a hinged Plexiglas lid. At the time everyone thought he was crazy to use Plexiglas, but he was trying to solve a design problem: Stereos with hinged turntable lids – wood or metal – rattled from the vibrations of the music. He sought out plastic so a listener would hear only the music, not the unit.

It was also cool and modern, like jazz.

An avid skier, he noticed in the 1970s that manufacturers of ski boots started using a hard, rubberized plastic to hold boots into ski bindings. On a mountainside in Switzerland, he had the revelation that he could incorporate that plastic into the contoured metal shape of a palm-sized electric razor.

In the end it was one of his designers, Roland Ullman, who developed the now-iconic Braun shaver with a bumpy rubber grip that would not slip out of the hand.

Dieter worked for Braun for four decades, until 1995. During that time he co-founded a furniture company, Vitsoe, known for its modular steel shelving. He did this while still working as head designer for Braun.

Although living in a house he designed in Kronberg, Germany, Rams, who is 87, still consults with Vitsoe in London.

“I’m basically retired,” he said. “My wife thinks I should be more retired.”

A designer in good company

The exhibition is not just about the imagination and insight of one man, but the vision of a company. When Erwin Braun took over his father’s radio company in 1951, he made design an integral part of the production process. Rams was hired to work directly with engineers to find the best way to make the best product — and to get the details right.

Braun and Rams, as chief of design, fostered a company attitude of innovation. They didn’t want to settle for making things people already wanted; they wanted to create products people didn’t yet know they wanted.

“Erwin was always dreaming in the beginning that he should not produce only products, but we should teach how people should live,” said Rams. “This was his idea.”

Braun even dabbled in urban planning. When the company headquarters moved out of Frankford, Germany, and into a more open, forested area in Kronberg, Braun wanted to design a company town with factories, housing, and retail, with all traffic running underground. He asked Rams and two other architects to design a carless city.

In 1967, the Braun company was acquired by Gillette. The new bosses had no interest in building a city of the future. All plans were scrapped.

In hindsight, Rams would have approached it differently.

“I would have started with landscape planning, not city planning,” he said. “We have to start with the landscape, then come to cities. We are on the way to disturb our planet. We are making too many mistakes.”

Rams used to have great admiration for companies like Apple, Sony, and the Italian typewriter manufacturer Olivetti, which made products designed to improve people’s lives, not just to sell more products. Now, he is hard-pressed to find a major company that does that.

“What company is doing well, together with design? I have no answer anymore,” he said. “We need entrepreneurs willing to work together with engineers and architects and designers to change our behavior, to teach the people … not always looking to see if enough people are buying it.”

Rams believes people should own fewer things, that work better: an attitude that is at odds with most manufacturers now fashioning products with their own obsolescence designed into them.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.