Benjamin Franklin Museum leaves bicentennial behind, reopens after two-year renovation

PROJECT FACTSHEET:

- Budget: $23 million

- Partners: National Park Service, City of Philadelphia, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Pew Charitable Trusts, Lenfest Foundation, William Penn Foundation, Knight Foundation

- Guest Curators: Remer & Talbott

- Exhibit Design: Casson Mann

- Interactive Design: Memory Collective, Bluecadet

- Exhibit Fabrication: Kubik Maltbie

- Architect: Quinn Evans

- Contractor: Daniel J Keating Company

Benjamin Franklin is a nearly mythic part of Philadelphia’s creation story and his presence is embedded in the city’s DNA, a storyline woven through our civic and cultural institutions. While he’s scattered everywhere, Franklin has been sort of homeless.

Where Franklin’s house used to stand off Market Street are “ghost houses,” an interpretation designed by Robert Venturi, John Rauch, and Denise Scott Brown for the National Park Service in the 1970s. And for the last 40 years the underground Benjamin Franklin Museum below Franklin Court was a bicentennial-era experience that was as much a museum of dated technology as one telling Franklin’s story.

Two years ago the National Park Service closed the Franklin Museum for a $23 million overhaul, financed through public and philanthropic sources, in an effort to ground Franklin’s legacy in Philadelphia anew. The goal was to wholly revamp the museum as the definitive place to learn about Franklin – the “relevant revolutionary” – as a man of his time whose ideas and actions have lasting power.

Starting Saturday, August 24 visitors to Independence National Historical Park will be able to walk into Franklin Court and the Benjamin Franklin Museum to see it with fresh eyes.

Franklin Court & Museum Entry

Not much has changed aboveground at Franklin Court. The ghost houses have been refreshed with a new coat of paint and the courtyard walkways and landscape have been given a welcome facelift by National Park Service crews.

The major change to Franklin Court comes though a compact new entry building for the underground museum, designed by the Washington D.C.-based firm Quinn Evans.

There was no question that the award-winning Venturi & Rauch ghost houses would be respected in a new design scheme for the museum, but Quinn Evans’ simultaneous challenge was to make a contemporary design statement in Franklin Court.

“In a lot of sites like this you will see the architects and landscape architects really trying to be invisible,” said Carl Elefante, principal at Quinn Evans, in a recent phone interview. But a minimalist glass box was not the aim here. Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown blessed the introduction of a new architectural intervention to the site, Elefante said, and invited Quinn Evans to become part of the site’s “entourage.”

“They said to us…accept the fact that you’re here and do something that reflects the fact that you appreciate the environment,” Elefante said, noting his admiration for the ghost houses. “We were kind of freed and empowered by that legacy to have some fun and feel that we could do something of that significance that we didn’t just have to get down on our knees and pray.”

That was a call to architectural arms at an intimate scale.

Quinn Evans’ programmatic charge was to connect Franklin Court to the underground museum through a new transitional space that clearly invites visitors into the museum; a place many visitors never realized was beneath their feet.

Quinn Evans worked through 13 design schemes over the course of several months, labored over mockups, and seeking a way to honor the intellectual honesty of Venturi Rauch’s work 40 years earlier.

The old entry building was a utilitarian brick block with a canvas awning, and the new structure is a play on the building it replaced. Instead of a lightweight canvas awning the new building features a weighty copper canopy, intended to give a sense of permanence.

“We played with making the brick building transparent and penetrable and inviting,” Elefante said.

The new structure swaps heavy brick walls for a ground-floor façade of “fritted glass” (glass with a pattern in glaze fired onto its surface) that remixes aspects of the former building. The designers derived the pattern on the glass from enlarged photographs of original brick pavilion’s brick wall. Taking it a step further, the glass panes are arranged in a Flemish bond pattern, which was the pattern of the bricks in the old wall.

The glass wall both creates a luminous transition space into the museum and will allow people in Franklin Court to see action inside the museum, hopefully drawing more visitors.

The exterior glass’s rust-toned glaze helps the wall recede a bit into the brick wall set back from the glass entranceway.

From afar the brick-textured glass is an eye-catching wash of russet ripples that reads as a nod to the traditional material, particularly if you notice the Flemish bond. Up close the abstract pattern is bold but indecipherable and a bit disorienting.

The interior glass has a different abstract pattern fired onto it that lends the windows a soft opacity that gives some heft to the thick glass walls.

The most deliberate gesture the Quinn Evans design makes to engage with Franklin Court is a large “view window” at the top of the museum’s interior stairs. Here the ghost houses are framed as visitors ascend from the museum below. Walk up to the large window and there is an interpretive panel and interactive display that tell the story of the ghost houses – a 21st century interpretation of the 20th century site interpretation.

UNDERGROUND MUSEUM

“You will know my house… you will be most heartily welcome,” is the quote from Franklin’s autobiography at the bottom of the museum stairs, but it’s hardly a recognizable sight.

In lieu of the burnt orange-tiled passageways leading into the museum’s depths, visitors now enter through a bright space with slate floors, past an admission desk (5 or $2 for kids 4-16, but school group will stay free) and descend into the new museum built in the footprint of the original one.

Nostalgics be warned: You are not in 1976 anymore.

Gone are the trippy mirrors, neon, and bicentennial funk. The beloved bank of slimline telephones to call Founding Fathers is nowhere in sight. (I sincerely hope it has been carefully preserved in a National Park Service time capsule somewhere for future generations.) This will doubtless be a disappointment for folks who loved the former museum’s time warp.

But if you can get past missing the museum’s former self, what might you see?

The new museum, while more staid, retains a sense of play and curiosity through new interactive exhibits, and there is far more substantive stuff to be learned about Ben Franklin.

Where the old museum was a throwback, the new one is decidedly of this time, featuring modern amenities (like a multi-purpose room and gift shop) as well as interactive exhibit design.

“That former museum was cutting edge when it was installed and I’d like to think that this is cutting edge now,” said curator Page Talbott of Remer & Talbott. “One of our charges was that this needed to stand the test of time with budgets as they are. [NPS] can’t afford to turn over permanent installations.”

While permanent is sort of a relative term, Talbott stressed that it’s very likely that the museum that opens this weekend will be the same in 10 years. Though not necessarily 40.

The new exhibits are designed around a series of several “rooms” focused on a different aspect of Franklin’s personality – duty, curiosity, strategy, ambition, and motivation to improve – in a move to get visitors to see Franklin as more human than mythic legend.

There is no right or wrong way to walk through the open “rooms” and in each space there is a layered approach that is likely to appeal to different kinds of visitors, from families to foreign tourists to Franklinophiles.

The new museum features more artifacts than the old one. Many of those on display, such as the beautiful family bible, either belonged to Franklin or are similar to things he created or owned.

“In the old museum there were very few original artifacts,” said Talbott. “[Now] there are about 20 or 30 loans from individuals and institutions that will join the objects owned by Independence [National Historical Park].” Some are on loan from local institutions like the Franklin Institute or the Library Company.

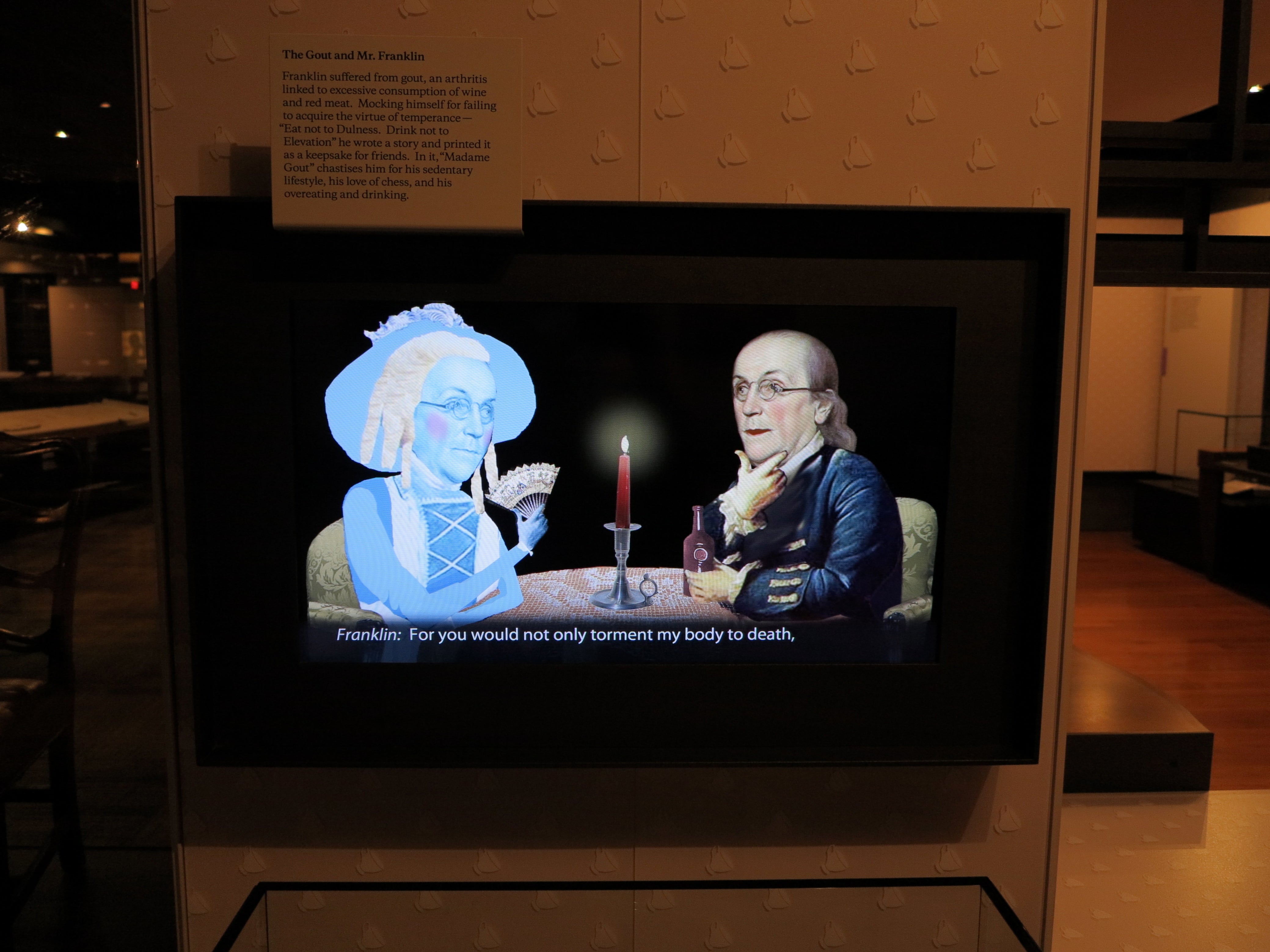

Seven videos animate artist Katherine Streeter’s collage-like depictions of scenes from Franklin’s life with cheeky dialogue, five of which were originally created for a traveling exhibit celebrating Franklin’s 300th birthday.

Kinetic panels cheer Huzzah! when visitors correctly match pieces of Franklin trivia, and touch screens also bring a host of sounds like whistles and pops into the room. They’re a lively and playful touch that could encourage engagement, but it remains to be seen just how much noise will be generated when the museum is at maximum capacity.

Franklin himself might appreciate is the way tech tools have been deployed to tell his story and create a deeper, interactive visitor experience.

Memory Collective created interactive tabletop touchscreens that allow visitors to explore elements of Franklin’s life and work, from the reach his work had on the city of Philadelphia to his complicated views on slavery (which remain unresolved among scholars). These experiences invite visitors to draw their own conclusions about Franklin the man and his enduring imprint on American and Philadelphian civic life.

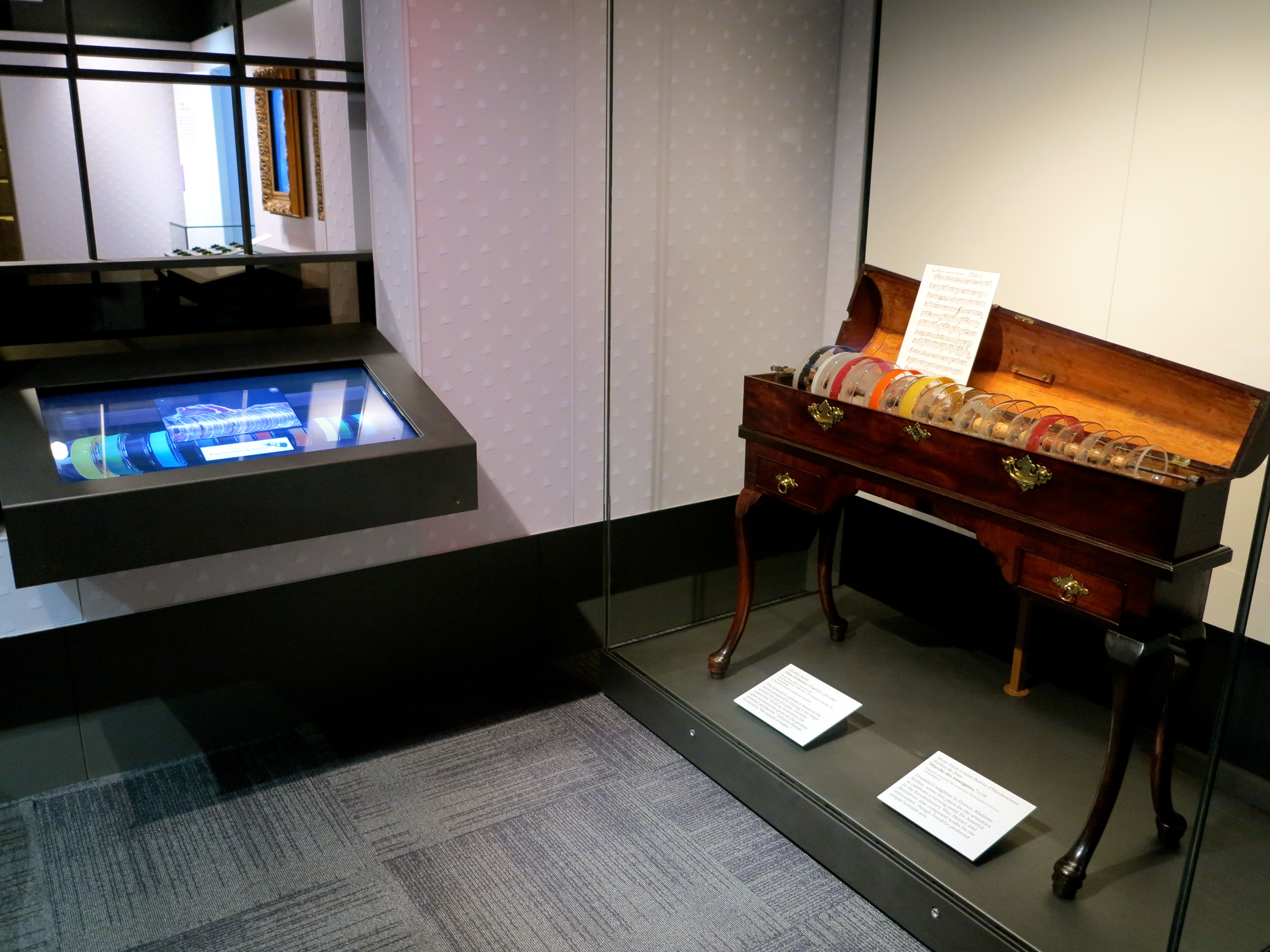

Interactive elements are designed to enrich visitor experience by adding a way to engage with an object or idea presented. Next to the Franklin-invented glass armonica, for example, there is a touch-screen panel where visitors can “play” an armonica, created by Philly-based interactive design firm Bluecadet.

“We were really careful about creating interactive experiences that extend the content,” Bluecadet creative director and founding principal Josh Goldblum said.

Given the previous museum’s dated technology, there was a consciousness that the tech tools here had to be enduring. “The technology is really in service of the content,” Goldblum said.

Bluecadet also created animated videos that are shown throughout the museum, starting with a 19-by-9 foot animation at the base of the entry stairs – in graphic black and white that introduces visitors to the museum’s themes. This stylized animation, and others in the museum, are based on a Charles Turzak’s 1930s biography of Franklin’s life, told through beautiful, graphic woodcut illustrations.

The woodcuts lend a timeless feel to a very contemporary and fresh expression of familiar stories from Franklin’s life.

“[Franklin] has been depicted by so many illustrators and artists we didn’t want to throw another one into the pile,” said Goldblum. So they ended up getting the rights from Turzak’s family to use his fabulous woodcuts.

The final museum experience is the “Library” which features shadow 3D bookshelves and a projected video created by Bluecadet showing a seated Franklin writing his autobiography. After presenting a version of his life story, the curators let Franklin have the last word.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.