Before Constitution Center honors, civil rights icon visits Camden and memories of MLK

Listen-

-

-

-

-

-

Hillary Clinton waves to supporters at Temple University. (Bas Slabbers/NewsWorks)

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

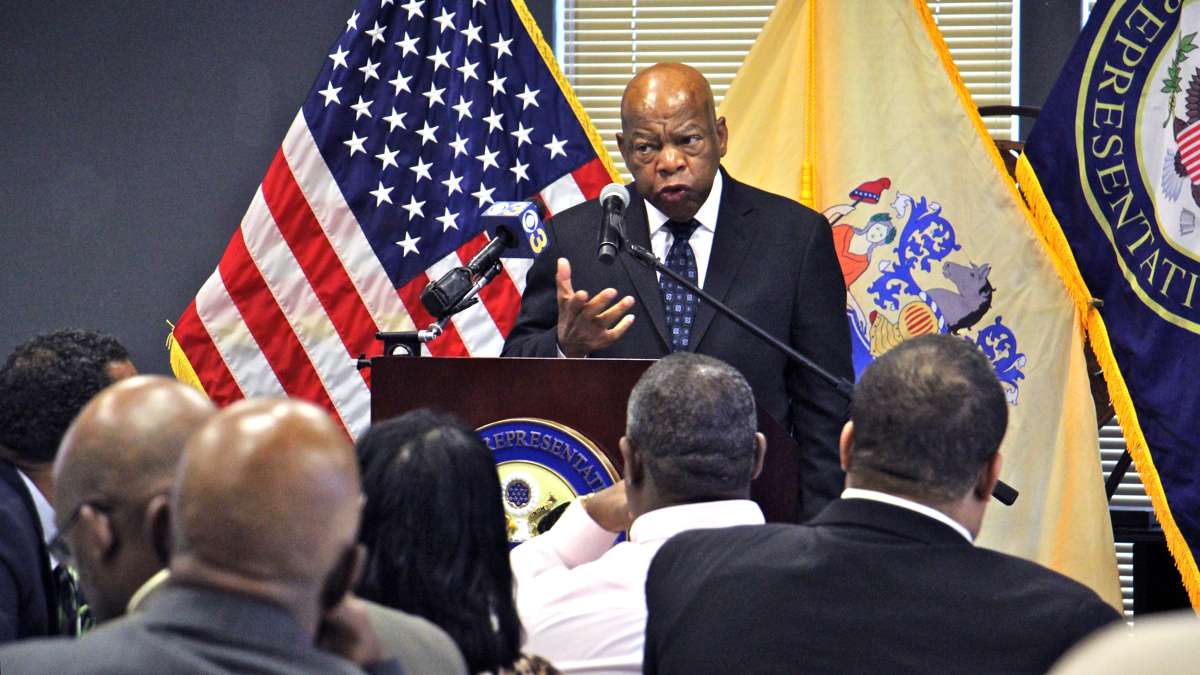

Monday night, the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia awarded the Liberty Medal to John Lewis, the longtime U.S. Representative from Georgia and icon of the civil rights movement.

The award ceremony honored Lewis for a lifetime spent fighting – at times putting his body on the line – for equality.

“You made me cry tonight,” said Lewis to the audience gathered on the lawn of the Constitution Center. “I will never, ever forget this evening.”

Lewis was just 23 when he helped coordinate the historic March on Washington with Dr. Martin Luther King, jr., and delivered an impassioned speech calling for civil disobedience. A few years later, while marching in Selma, Alabama to register black voters, he was brutally beaten by police, who fractured his skull.

Now 76, he is just as fiery as ever.

“Never ever get lost in a sea of dispair, never become bitter or hostile because hate is too heavy to bear,” he said. “Be hopeful, be optimistic, be happy, and continue to press on until we build a nation and a world community at peace with itself.”

Before receiving the award, Lewis spent much of the day across the river in Camden.

The morning rain let up just as Lewis arrived at a blighted block of Camden and a boarded-up house on Walnut Street where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. stayed in the 1940s as he studied at a nearby seminary.

This is where King lived when he performed his first act of civil disobedience — an impromptu sit-in at a diner in Maple Shade that had refused him service. Neither the seminary nor the diner exist anymore. The house — which has been unoccupied for two decades, its interior stripped of all metal by vandals and scrappers — is the last thing standing to tell the story of King’s entry into activism. A local preservationist is pushing the state of New Jersey to declare the house an historic landmark.

From preaching to politics

Outside the house, Lewis addressed local officials, clergy, and community organizers under a tent. He described growing up the son of sharecroppers, wanting to be a preacher. As a child, he was in charge of the family’s chickens; he and his siblings would gather the chickens together in the yard as a kind of clucking congregation, and play church.

“I would start preaching,” said Lewis. “Some chickens would nod their heads, some chickens would shake their heads. I could never get them to say ‘amen.’ Some of those chickens I would preach to listened to me more than our colleagues in Congress. Some of them were more productive.”

Lewis recalled the first time he met King. At 17, he wanted to go to a nearby college that accepted only white students, so Lewis wrote King a letter asking for help. King responded with a round-trip bus ticket. When was 18, Lewis he took a Greyhound from Troy to Montgomery to meet King at the Rev. Ralph Abernathy’s First Baptist Church.

“I was so scared, I didn’t know what to say or do,” Lewis remembered. “Dr. King said, ‘Are you John Lewis? Are you the boy from Troy?’ I said, ‘Dr. King, I am John Robert Lewis’ — I gave him my whole name. He started calling me ‘the boy from Troy.'”

That relationship bloomed a few years later when Lewis helped King coordinate the March on Washington in 1963. Then, in 1965, Lewis led a march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, that resulted in a violent clash with police. Lewis suffered a fractured skull at the hands of police.

Now 76, Lewis is a longtime congressman who still organizes acts of civil disobedience. This summer, he staged a sit-in at the Capitol over a gun-control bill which had been voted down.

“John led an effort on the House floor that was really quite remarkable — certainly in my short tenure, but really in the history of Congress,” said U.S. Rep. Donald Norcross, speaking to members of the clergy and the NAACP at a luncheon in Camden. “This was not contrived in some room up on K Street. This was as real as it gets.”

Norcross then introduced Lewis, whose resonant voice and rolling cadence recalled the preacher he once aspired to become.

‘The way of peace’

“In my own district, in my own city of Atlanta, I’ve been to too many funerals,” said Lewis. “We must find ways to teach people the way of peace, the way of love, the way of non-violence.”

He made no mention of any future legislation to curb gun violence. Instead, he advocated grass-roots, community-building efforts to challenge the influence of the National Rifle Association.

“Many of you won’t know this, but I attended seminary for four years,” said Lewis. “We were taught that in the bosom of every human being is a spark of the divine. You have to respect it, and you don’t have the right to destroy that spark or destroy that human being.”

Lewis has published a memoir as a three-volume graphic comic book, “March,” to inspire younger readers. Former governor Ed Rendell used the award ceremony to announce that his organization – the Rendell Center for Civics and Civic Engagement – will donate 368 copies of “March” to every 5th grade class in Philadelphia, and 50 copies to every library in the city.

On Tuesday, the day after his acceptance of the Liberty Award, Lewis will remain in Philadelphia to launch a campaign to register Democratic voters in Pennsylvania.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.