Award-winning vintage car museum reaches 10th year, still waiting for crowds in Southwest Philly

The Simeone Museum of classic racing cars celebrates its 10th anniversary, winning awards but still looking for its audience.

-

Dr. Fred Simeone stands amid his collection at the Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum, which traces the history of auto racing and emphasizes the value of competition as a spur to progress. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

Alfa Romeo racers from 1937 and 1975 share the stage that evokes the streets of central Italy, where the Mille Miglia road race was held. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

A 1921 Vauxhaul from England excelled in hill-climb races, some of which required four passengers to test the competitive strength of the vehicle. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

A hood ornament gleams on a 1928 Stutz BB Blackhawk Speedster, America's fastest car in 1928. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

A classic car gets a sprucing up at Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum in South Philadelphia. Nearly all of the cars in the collection are driveable. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

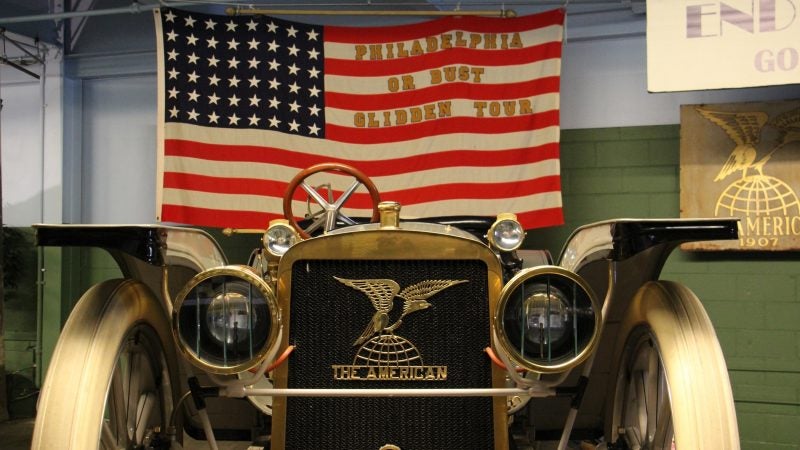

A 1907 Renault Racing Roadster at the Simeone Museum is one of 11 sold and one of four known to exist intact. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

-

The Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum in South Philadelphia is celebrating its 10th anniversary with free admission on June 8. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

One of the finest collections of vintage racing cars in the world is now celebrating its 10th anniversary in Philadelphia. Still, the Simeone Foundation Automotive Museum in Southwest Philadelphia, is unknown to many in the city.

It founder, Fred Simeone, sees himself as the Albert Barnes of classic cars. Like the famous doctor who used his personal wealth and good eye for art to amass a world-famous collection of impressionist and modernist paintings, Simeone is a retired neurosurgeon who started snapping up vintage sports cars in the 1970s, when they could be had relatively cheaply.

“We were never concerned about the values of the cars,” said Simeone. He bought all the cars personally and donated them to his organization, the Simeone Foundation. “If we bought a car, it was because of its historical interest, and we just kept it.”

Over 50 years, Simeone acquired 65 sports cars, ranging from 1910 to the 1970s. He had strict collecting criteria: All of the cars are production models – meaning they were manufactured to be driven on typical city streets; all of them raced competitively, several winning major European races; and, taken together, they represent the evolution of engineering and design.

With few exceptions, they operate — even the ones over a century old. The museum has an in-house shop to keep all the engines in working condition. Every other weekend the museum lets visitors watch, listen, and smell the cars as they drive around the parking lot.

“Like Barnes, I was a crazy doctor from Kensington,” said Simeone. “He was far more visionary, but he wanted to tell his story. A visitor to the museum should leave with something more than what he came in with. It can’t just be eye candy.”

The Simeone museum is arranged both geographically and chronologically, with tableaux of landmark races — the French Le Mans, the Italian Mille Miglia, and the British Brooklands. Each diorama shows cars that raced in those contests, arranged by year.

The collection ends in the 1970s because, Simeone says, that’s when cars started being built purposely for track racing. Instead of modified sports models, track cars became highly specialized and impractical – even illegal – for anything else.

Like Albert Barnes, Simeone is using his collection for educational purposes — teaching kids engineering, design, and something about life.

“Competition is how you succeed in life,” he said. “It’s how we evolved. It’s the basis of progress. Sadly, American youngsters are not the world leaders as it applies to math, technology, science.”

Paraphrasing Henry Ford, Simeone likes to say that the first race was conceived after the second car was built. “That’s how guys are,” he said. “You want to see who had the fastest sports car.”

This summer, the museum is introducing a camp program to spur interest in the aesthetics and engineering of automobile design.

Despite having won a string of museum awards and recently being named by the Classic Car Trust the No. 2 car collection in the world, the museum has always had low attendance.

“We haven’t caught on in Philadelphia for 10 years,” said Simeone. “On weekends, we have more foreign visitors than American visitors.”

Simeone is hopeful that interest will grow as prices for vintage cars at auction begin to reach the same levels as paintings by the old masters. Rightly or wrongly, as Barnes learned, people tend to follow the money.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.