As planning continues for 30th Street Station, grand plans in D.C. offer vision of future

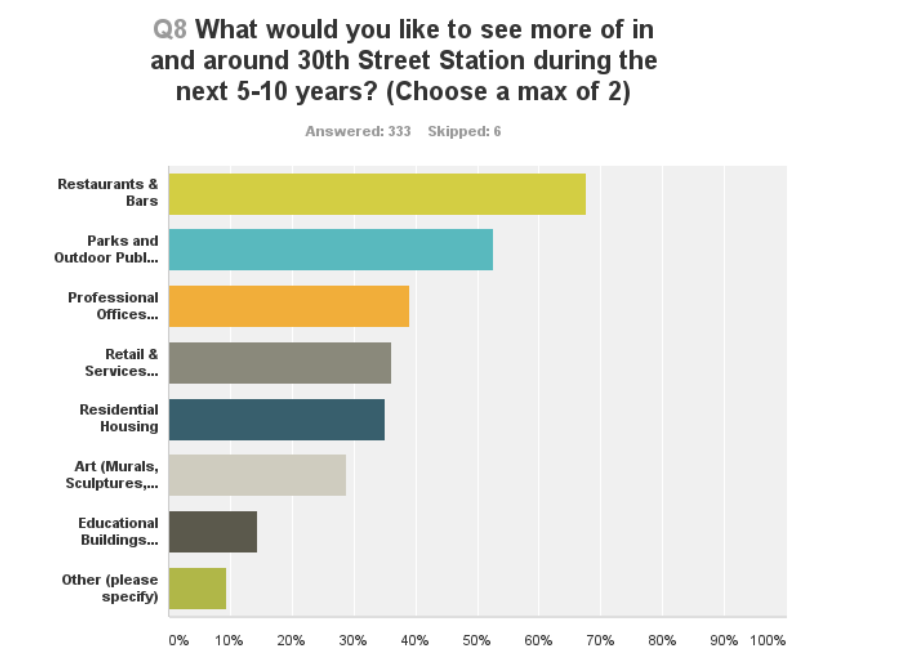

The Philadelphia 30th Street Station District Plan recently asked the public what they wanted to see in and around Philadelphia’s Amtrak station and the results are in.

The survey of 339 respondents revealed strong preferences for more bars and restaurants (picked by close to 70 percent of respondents, who could pick up to two options), and for more parks and outdoor public spaces (over 50 percent). Offices, retail and residential housing followed, all getting between 45 and 50 percent.

The respondents were predominately male and under 35, potentially skewing results. As a dude in his early 30’s, I think that just about every place in the world could do with more spots for outdoor day drinking.

Still, the findings do illustrate a demand for mixed-use development in the area and a continuation of the work that the University City District has done in creating and expanding the Porch and that Drexel University has done west of the station as it expands under President John Fry’s tenure.

The 30th Street Station District Plan is a collaborative effort led by Amtrak, Brandywine Realty Trust, SEPTA and Drexel. Brandywine built the Cira Centre to the immediate north of the station and is currently building on another larger tower three blocks south. Drexel has been expanding its campus eastward, towards the station.

The survey is the first step in a multiyear process asking a basic question: what should 30th Street Station, and the surrounding area, look like in the coming years?

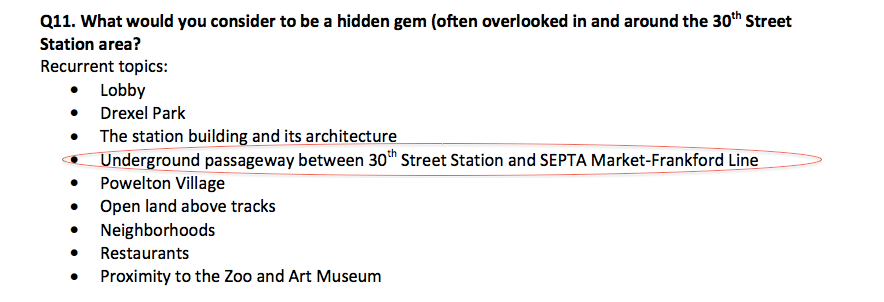

The Inquirer’s Paul Nussbaum, echoing Senator Bob Casey, recently suggested Washington’s Union Station. Union Station is in many ways a big brother to 30th Street: a larger, older Beaux-Arts masterpiece home to a multiple restaurants and bars, a sizeable shopping mall, and an intercity bus terminal. On top of all that, passengers can easily access DC’s Metro subway from Union Station; 30th Street’s connector tunnel to SEPTA was closed during the city’s ebb in the 80’s and has yet to reopen.

But hoping to emulate today’s Union Station is a vision far less ambitious than the one proposed by Drexel’s Fry. Drexel is funding a separate, $4 million engineering study to consider the feasibility of capping the rail yards north of the station, in order to develop the air rights over those tracks.

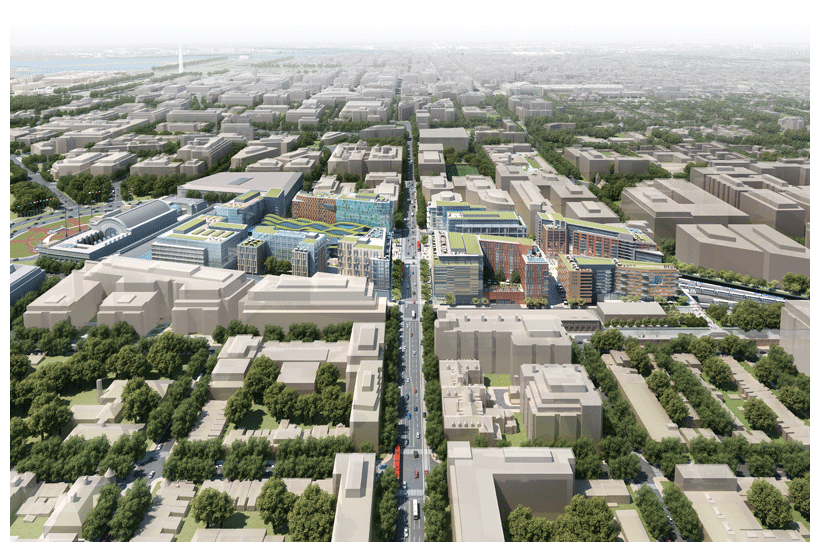

The Union Station Redevelopment Corporation shares a vision for its own rail yards. It recently unveiled preliminary plans for developing the air rights over 14 acres of tracks leading into Union Station with 1.5 million square feet of office space, 1,300 residential units, 100,000 square feet of retail space and over 500 hotel rooms, plus parks and plazas, too. The project will be called Burnham Place, after the Station’s architect.

Union Station’s new Burnham Place will feature the kind of mixed-use development that the 30th Street survey’s participants seem to want, and almost exactly what Drexel has proposed.

In a way, DC is actually emulating Philadelphia. In the 1950s, Edmund Bacon led the charge to remove the Chinese Wall, the Pennsylvania Railroad’s massive above-ground viaduct stretching from Broad Street Station across from City Hall all the way to the Schuylkill. Bacon succeeded, building Penn Center on the blocks once occupied by train tracks.

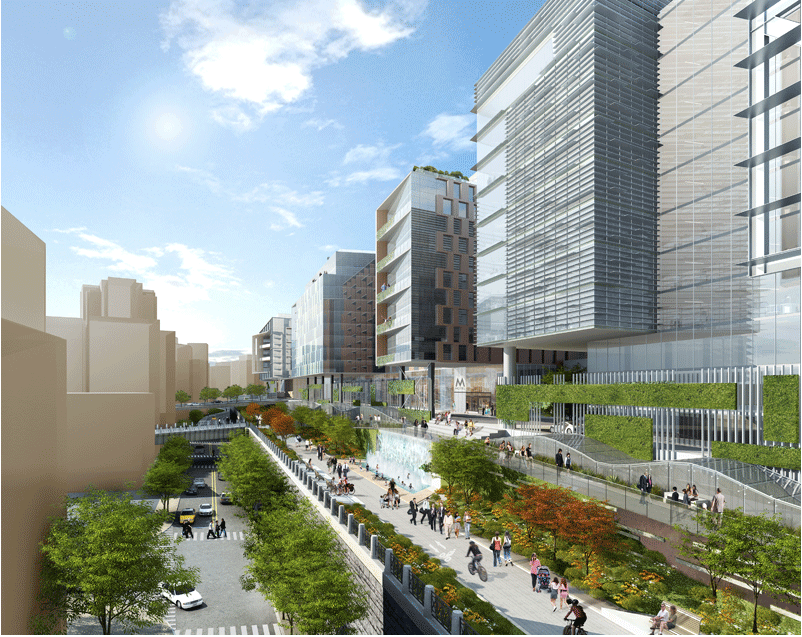

Over the course of the ensuing 60 years, though, planners and developers alike have learned to avoid shoving pedestrians and retail underground and to embrace mixed-use development, green spaces, and focus on place-making. Burnham Place would feature greenways and lots of seating for al fresco dining.

Burnham Place will take decades to build, as would any development over the 30th Street Station rail yards. And Burnham Place only makes financial sense because of Washington DC’s continuing revitalization and the steady growth of the neighborhoods surrounding Union Station. While 30th Street Station’s location along the Schuylkill River makes it more attractive, land values in Philadelphia are decidedly less than in the Nation’s Capital.

Both Burnham Place and any Philadelphia rail yard-capping project would follow Manhattan’s Hudson Yards. That is a 26-acre project, the largest private real estate development in New York City’s history.

Still, Union Station’s plans provide 30th Street Station boosters another example to point to. New York has its Grand Central Terminal; London, it’s St. Pancras Station. Now Washington hopes to transform Union Station. Might 30th Street join the ranks of train stations that are destinations unto themselves, rather than mere boarding platforms?

Maybe. Even without capping the rail yard, there is plenty of room for new development in and around 30th Street Station. Its north waiting room is woefully underutilized and placing dozens of tables and seats on the building’s south end makes about as much sense as the indoor umbrellas they’re festooned with.

But capping the rail yards would be truly transformative. To put things into perspective in just how massive this project could be: Burnham Place is 14 acres; Hudson Yards, 26; a Philadelphia rail yard cap would be 50 acres. It’s a colossal vision for a city that has trouble dreaming big.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.