Artist re-imagines war-torn landscapes to see what we’ve lost

There is the art of war, and then there is war art. Some artists glorify the victory of the battle while others offer commentary on the destruction. Goya’s The Disasters of War series was a protest against violence, and in the first half of the 20th century, Kathe Kollwitz humanized the tragedy of war. Otto Dix revealed the brutality in the aftermath of war in his depictions of legless and disfigured veterans during Germany’s Weimar Republic.

“Who caused what the picture shows?” asked essayist and photography critic Susan Sontag. “Who is responsible? Is it excusable? Was it inevitable?”

“The rubble that each war leaves behind is carried into the future, whether physically, psychologically, culturally or spiritually,” writes artist Susanne Slavick. “Artists record, remember, reflect, re-purpose and restore that rubble—materially and conceptually, literally and metaphorically.”

The title of Slavick’s exhibit at the Bernstein Gallery through Feb. 13, R&R (…&R), takes the military acronym for rest and relaxation to suggest words like regret and regenerate, remorse and restoration.

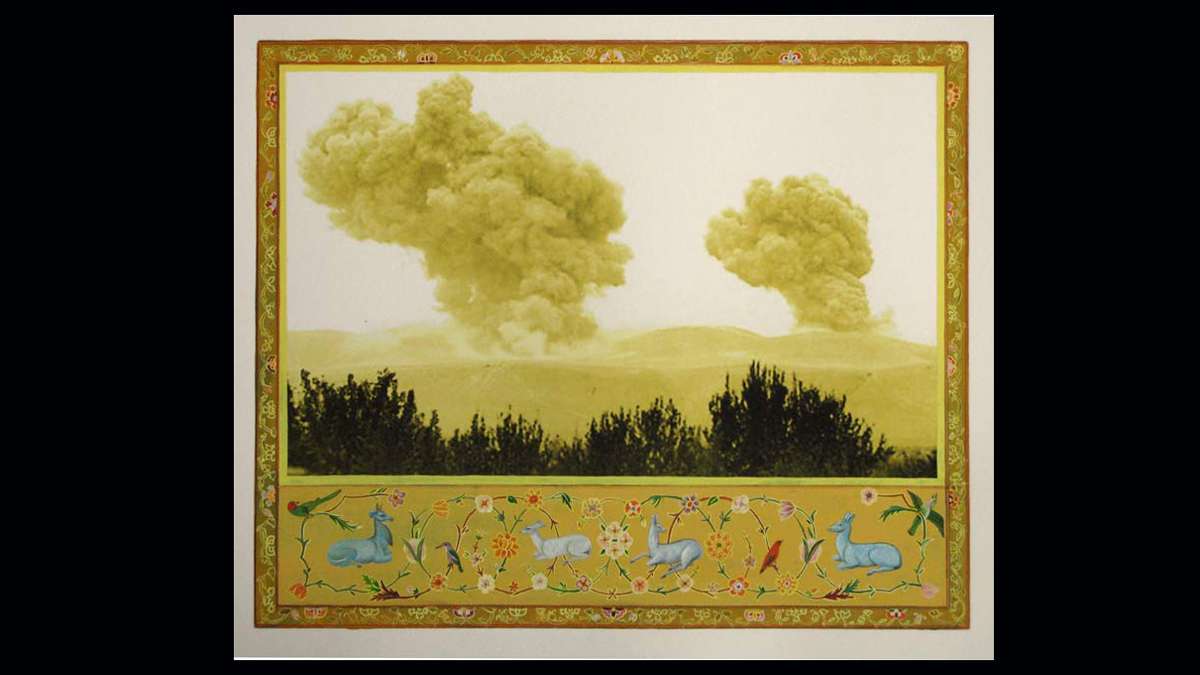

Beginning with “found” photographs that circulate on the web, Slavick paints intricate imagery on the decimated buildings and gaping earth, borrowing art traditions from the country whose photograph she appropriates, whether from the workshops of Persian miniaturist Bihzad or the court arts of Safavid Iran. Scenes of construction and cultivation are painted over digitally manipulated photographs of devastation across the former Islamic Empire – Afghanistan, Iraq, Lebanon and elsewhere.

“Altering these found images by hand is my attempt to recognize and reconstruct – if only through imagination – what has been decimated… I hope to remind us of what we have lost and what we might regain,” says Slavick, Andrew W. Mellon Professor of Art at Carnegie Mellon.

The largest work is a starkly black and white image with few shades of gray – a monolithic building in the night evokes buildings we’ve seen in news photos of war-torn regions, usually with innocent victims peering out wondering what’s next. Here there are no people, only darkness, and the artist has painted billowing white curtains on some of the openings, suggesting life that once was. Now only a whisper of a spirit creates a breeze that stirs the drapery.

Titled “Remorse: White Curtains,” the original photograph is from an image of war and destruction in Beirut. “Details like these curtains mourn an absence and reveal that people once went about their daily lives just like we do ours,” says Slavick.

A series of five images, “Equus,” shows a silhouette of a man atop a horse mounted not on a marble pedestal but over rubble – the mangled machinery in the aftermath of improvised explosive devices. The silhouettes are from equestrian statues those monuments to war heroes we see in every town and city plaza.

“Whether villains or good guys, they represent those who use violence as a means to an end,” says Slavick. “The easy reverence they elicit as monuments belies the empty heroism that history sometimes exposes or forgets.”

The horses’ tails have been combed into long tresses, beautifully articulated with pen and ink. “They get trampled by their own bravado and caught in the machinery,” Slavick writes.

An improvised explosive device is also at the base of “Resplendent,” from which a finely painted tree, derived from an ancient Persian illustration, grows, once again juxtaposing the magnificent art history of the region to today’s battleground.

“I make no claims to master status or perfection through my imitation and repetition,” says Slavick, referring to Pulitzer Prize-winning author Orham Pamuk’s novel “My Name is Red,” in which miniature artists from the Ottoman Empire no longer need to see what they create because they have copied it so many times they have imprinted it in their minds. “I certainly have not seen any of the scenes that I have depicted,” continues Slavick, “but I honor and am honored in this ongoing dialogue with painters of the past.”

Slavick hand paints stylized waves at the edges of craters in bombed Lebanese roads; a decorative Persian border rises from a bombed and fallen bridge span; a Persian miniature figure in a turban wields a baton under an ornate gate amid the rubble of Saddam Hussein’s bombed out palace; a 16th century Persian painting of a horse stands on the edge of a crater of a bombed bridge in Mosel, Iraq. Magnificent dragons appear with a dark gray cloud resulting from the U.S. bombing of Baghdad.

The artist’s attempt to reconstruct the beauty of the past is a step in healing and regenerating.

Susanne Slavick: R&R (…&R)Bernstein Gallery, Princeton UniversityThrough February 13, 2014

____________________________________________________

The Artful Blogger is written by Ilene Dube and offers a look inside the art world of the greater Princeton area. Ilene Dube is an award-winning arts writer and editor, as well as an artist, curator and activist for the arts.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.