Anti-Asian propaganda on display in City Hall

A private collection of historic racist ephemera offers lessons on how we see ‘others’.

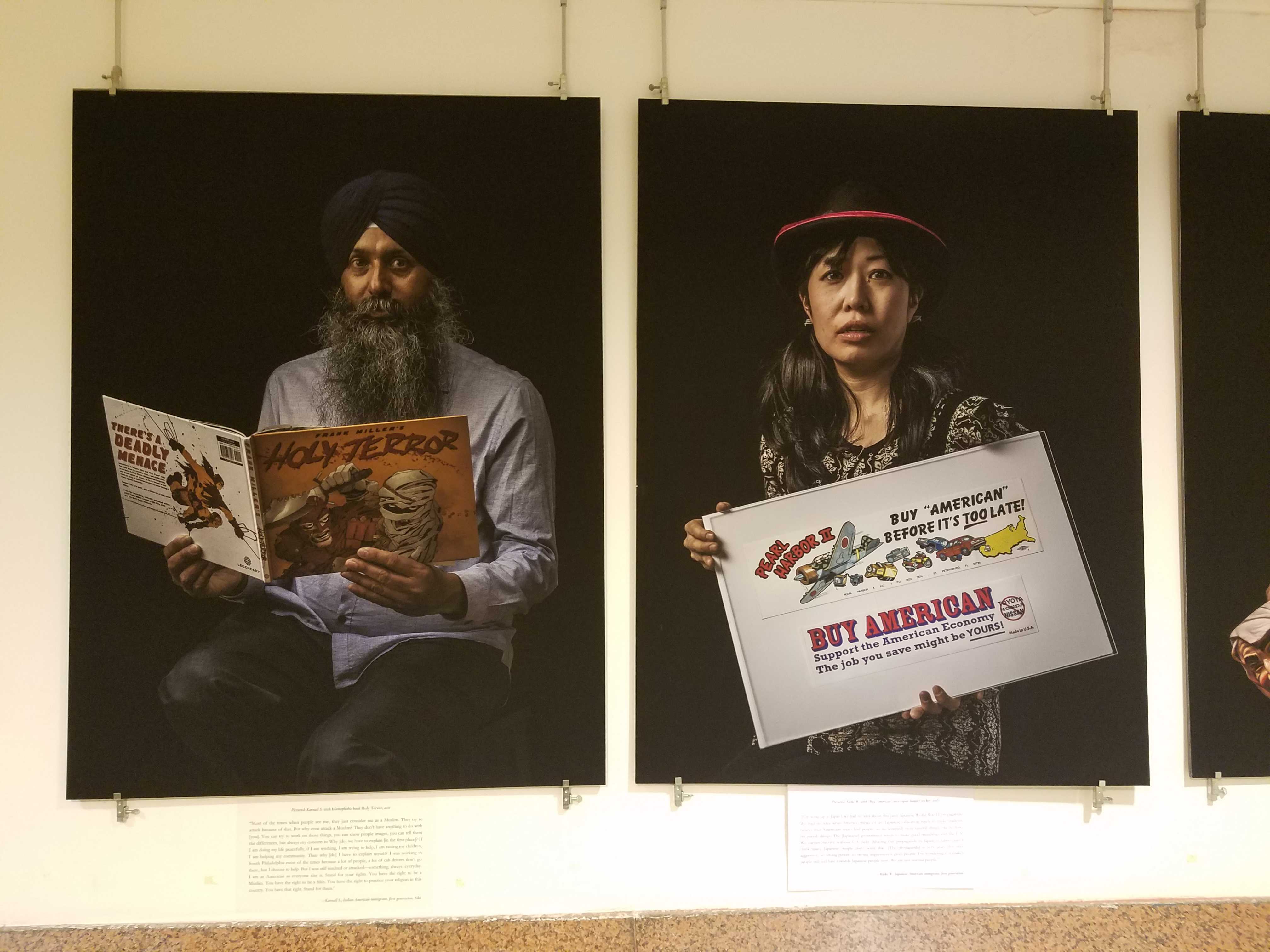

Teresa M. and Hiro N. (Photograph by Justin L Chiu)

Rob Buscher is a collector, usually picking up things that show Asian Americans in a positive light. The former director of the Philadelphia Asian American Film Festival (and current program director at the Fleischer Art Memorial) is particularly drawn to Asian Americans who appeared, with a certain degree of glamour, in early Hollywood movies.

But when he saw a vintage World War II poster warning Americans against the scourge of the Japanese, he knew he had to have it. The poster advised factory workers to practice safety protocols on the job, lest the Japanese get the upper hand. A menacing Asian face glares in the sky through flames.

As an adjunct professor of Asian American studies at the University of Pennsylvania, he knew about the prevalence of anti-Japanese sentiment during the war, but to see it in a full-color poster that he could hold in his hands was a different story.

“To see something like this was a gut punch,” said Buscher, who saw the poster in a 2017 antique fair at the Kimmel Center. “It changed the way I thought about physical artifacts.”

That poster launched a collection he and his wife have amassed of about 150 objects, mostly anti-Asian propaganda. About half of that collection is currently on display on the second and fourth floors of Philadelphia City Hall as part of the Art in City Hall program.

Referencing the “yellow peril” history of anti-Asian racism in the US, the exhibition — called “American Peril” — is mostly ephemera: posters, postcards, magazines, advertisements, buttons, t-shirts, and sundry items that were not designed to last very long.

A bulk of the collection is from World War II, when America was fighting Japan, Germany and Italy. While it might not be surprising that a lot of printed material would emerge demeaning the nation’s enemies at that time, the caricatures of Japanese were arguably the most crude and dehumanizing. The illustrated covers of Collier’s magazine showed Germans and Italians as ugly and sinister, but a Japanese military officer is depicted as an ape. An ashtray featuring a caricature of a Japanese person drawn as a rat instructs the viewer: “Jam your cigarette butts on this rat.”

“The level of dehumanization far exceeds anything being applied to the Italian and Germans,” said Buscher. “You might say, ‘It’s a point of satire and someone of that era would not take it at face value.’ However, the reality is most people didn’t interact with these types of communities. There was only a limited perspective of who these people are.”

In 1943, Life magazine published photos of decapitated heads of Japanese soldiers, which American soldiers had stolen from corpses as war trophies. It is estimated that after the battle for the Mariana Islands in 1944, about 60% of the Japanese dead were mutilated for trophies.

In January, when Buscher put this exhibition together, America was on the brink of war with Iran, so he arranged the items to draw out similarities between anti-Asian and anti-Muslim propaganda.

The collection has objects gleefully encouraging the killing of people from the Middle East. Some date to the Gulf War of the 1990s, when entrepreneurs adapted the famous Camel cigarettes slogan “I’d walk a mile for a Camel” to “I’d fly 10,000 miles to smoke a camel,” accompanied by a camel-riding man in traditional Muslim clothing targeted in crosshairs.

Others date to post-9/11, when shooting range targets were printed with pictures of men wearing turbans. Still others combine the two: a “body bag” made of burlap was printed with the figures of Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden with crosshairs over their faces.

The anti-Muslim imagery goes back to the 1930s with “Ken” magazine, a short-lived political bi-monthly, which put on the cover a grotesque caricature of a Muslim man with the headline, “The Coming Moroccan Revolt.”

“These kinds of conversations don’t come from nowhere,” said Buscher. “We could say that 9/11 caused negative reactions of anti-Islam bigotry. That’s not the case. When we look at the history of depictions of the racialized ‘other’ in the 1930s, to the Iran Revolution of the 1970s, the Gulf War of the 90s, there is a long history of linkages and connections.”

To make his collection contemporary, Buscher worked with photographer Justin Chiu to make formal portraits of people of Asian and Middle Eastern descent holding objects from the collection.

For example, a man identified as Ed N. was born in a Japanese internment camp in 1943. He is shown wearing a white baseball hat showing a crossed-out Japanese flag and the words “Buy American.” The hat is from the 1980s when American and Japan were in a trade war.

Ed’s parents met in 1942 while incarcerated in an internment camp.

“I describe myself as an authentic product of American racism,” said Ed N. in the wall text accompanying his portrait. “[It’s] one of the ironies of my life.”

Buscher wanted the portrait subjects to showcase items attacking them personally, to recreate the visceral reaction to propaganda that he felt that day in the antique fair when he bought the WWII factory safety poster with the sinister Japanese face illuminated by fire.

That poster is shown in a portrait featuring Hiro, who was incarcerated in an internment camp in Arizona.

“The horrendous nature of some of this [propaganda] attracts attention. In today’s context, they may seem ludicrous,” Hiro is quoted as saying in the wall text.

He hopes the exhibit will provoke people into thinking, “Okay, today we’re not that bad, but maybe I should pay more attention to the issues of today that are built on similar kinds of perceptions, hatred, racism, etc.”

Since “American Peril” went up at the beginning of February, the national discussion has shifted away from potential war with Iran and toward the threat of the COVID-19 coronavirus.

Nevertheless, the lessons of historic racism still apply: in the time Buscher’s anti-Asian propaganda has been displayed in City Hall, anti-Chinese racist incidents have been reported around the country and the world as fears of Asians carrying infection sweeps across the globe.

“American Peril” will be on view until March 20.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.