Former Mütter Museum forensic anthropologist launches research institute

Longtime Mütter Museum forensic anthropologist Anna Dhody will continue her work analyzing historic samples, but now in a research institute of her own.

Former Mutter Museum forensic anthropologist Anna Dhody will continue her work at a new institute named after her. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

From Philly and the Pa. suburbs to South Jersey and Delaware, what would you like WHYY News to cover? Let us know!

Long-time Mütter Museum forensic anthropologist Anna Dhody will continue her work analyzing historic samples, but now in a research institute of her own. Dhody has distinguished herself in mining centuries-old human remains and tissues for modern insights.

In 2007, a researcher called Dhody and asked for samples of human intestines with cholera to study what the disease was like more than a century ago. At the time, Dhody was at the Mütter Museum. The popular medical history museum has a large collection, including human remains and tissues.

“I looked at my database, and I go, ‘Oh, I’m sorry. I don’t have an intestine with cholera, I have six,'” Dhody recalled. “There were jars that were covered in like a pig’s bladder with a lead disc and painted with this kind of black pitch. It’s not something you could just unscrew and then screw back in again; we know that they hadn’t been touched.”

The samples came from a cholera epidemic in Philadelphia in the mid-19th century that killed over 1,000 people. Dhody joined some researchers in studying the DNA of cholera from those samples.

After years of work, they published their findings, including the conclusion that the disease is only a few hundred or thousand years old, and not tens of thousands of years old, which is what scientists previously thought. This meant the disease mutates faster than what scientists had previously assumed. This was the first time scientists had studied a sample of the disease that goes back further than the 20th century.

Cholera is less deadly nowadays, but the disease is still around. An outbreak in Lebanon two years ago killed 18 people and infected thousands across the country.

Dhody’s new research institute is dedicated to studying human health using historical samples, advising museums on their collections, and promoting science education.

The move comes a few months after she left the Mütter Museum, where she had worked for almost 20 years. She said she left because of disagreements with new leadership, such as their decision to suddenly remove all of the museum’s educational YouTube videos last year in the name of a content review. Many other staff have also left the museum, and some of them are joining Dhody at her new institute.

Other experts say Dhody’s focus on historical samples is a promising line of inquiry for many scientists, as it could shed light on how a virus or disease evolves and changes over time.

Jeffrey Withey, a microbiologist at the Wayne State University School of Medicine who specializes in cholera, said that without studying historic samples, scientists have had to assume that the older forms of the disease behave like their modern counterparts.

“Until we actually look at these genomes and get the data, we can’t really say that with any kind of certainty,” he said. “A lot of … what we say about these things is dogmatic but not really based on data.”

He said anybody who studies a disease-causing organism would be interested in how that organism has changed over time, as part of the constant battle with the human body’s defenses.

Dhody’s current research projects go beyond the cholera work that started it all.

“I’m continuing this legacy of looking at historical medical collections as bio repositories of … infinite medical knowledge that can help us. I like to say that the answers are there; it’s just up to us to ask the right questions.”

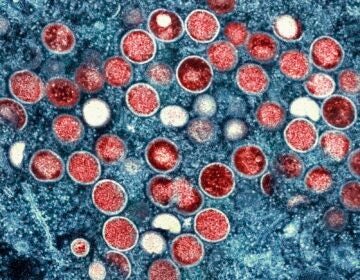

One of her ongoing research projects is a study of smallpox viruses, using traces of the vaccines left behind on vaccine kits dating back to the 19th century.

Back then, doctors made vaccines from samples passed to each other. For example, English doctor Edward Jenner vaccinated the first patient against smallpox by using material from another person’s cowpox sore.

“They vaccinated their patients, and then they propagated, and they passed it on,” Dhody said. “I kind of jokingly say it’s like a sourdough starter with consequences.”

This builds on work she had co-authored and published in 2020, studying smallpox from vaccination kits dating back to the American Civil War.

This research can challenge assumptions scientists used to have about smallpox, said molecular anthropologist Ana Duggan, lead author of the 2020 research and adjunct professor at McMaster University in Canada. For instance, scientists used to think that smallpox had been circulating for as long as 10,000 years. However, Duggan’s earlier research estimates that the common ancestor of modern smallpox virus goes back to the 16th to 17th century — just a few centuries ago.

“When I speak with people in the medical history field … they’re really excited by that research and they’re always interested to hear more,” Duggan said.

This kind of research is also essential for animal and plant diseases, said plant pathologist Jean Ristaino, a professor at North Carolina State University.

“It’s really important to understand human diseases, just like plant and animal diseases in the past, that could raise their ugly head again at some point in the future,” she said.

She studies the pathogen that caused the Irish Potato Famine in the mid-19th century, which led to a million people dying from starvation and disease. Part of her research involves studying plant samples that date back to the famine to understand the evolution of the disease. One of her findings is that the disease did not come from Mexico, which is what researchers had thought; instead, she traced it to the Andean region of South America.

She pointed out that the disease still exists and requires multiple fungicide applications to control. She added that understanding the origin of the disease can help in the search for resistant potatoes that have long evolved in the Andean region with the pathogen.

She did her research using ancient plant samples and said these collections are under threat. For example, Duke University recently made the controversial decision to shut down its herbarium and disperse the specimens.

Dhody is eager to start this new chapter after almost two decades at the Mütter Museum, where one of her more public-facing roles was making videos that explain medical history. She said that when the museum’s new leadership decided to take all their videos down a year ago, she realized she and the leadership had different visions for the museum.

“Leadership will do what it feels like it needs to do, and you have a choice: you can either stay and fall in line … or you can move on if you’re not in agreement.”

She said she is very grateful for her career at the Mütter Museum and will look back fondly. But now she is excited to conduct research with her own team in what she calls a grand experiment.

Get daily updates from WHYY News!

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.