An old prison wall in Philly connects inmates to the outside through animated films

Prison walls are designed for separation. A new installation at Eastern State Penitentiary in Philly flips that defining characteristic on its head.

Listen 3:40

Inmates gather to watch the animated videos they created for 'Hidden Lives Illuminated,' a project of Eastern State Penitentiary. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

Prison walls are designed for separation. A new installation at Eastern State Penitentiary flips that defining characteristic on its head.

Over the next four weeks, the “living ruin” in Philadelphia’s Fairmount neighborhood is hosting film screenings of hand-drawn animations. Created by people currently incarcerated at one of Pennsylvania’s largest prisons, the pieces will be projected on those barricades — with the goal of bringing people closer.

“We want to use the walls of Eastern State Penitentiary to bring people together, to bring voices from the inside to people from the outside,” said Sean Kelley, project lead senior vice president and director of interpretation at Eastern State Penitentiary.

Inspired by a similar project in Chicago, 19 people behind bars at SCI Chester made short animated features that tell personal stories. The videos wade into some pretty weighty subjects, like the impact incarceration has on families, restorative justice, and general prison life.

A group of people incarcerated at Philadelphia’s Riverside Correctional Facility for Women also made a collective video with similar themes.

“Most people who are living in prisons are really interested in making the world a better place in some way,” said Kelley. “They wake up in the morning and their environment tells them that they’ve created harm and they are trying to find a way to create good in the world.”

Though this is about more than portraying incarcerated people in a different light. Each screening will be followed by discussions and presentations about the criminal justice system.

WHYY spoke to inmates at the Delaware County men’s prison about their participation in the “Hidden Lives Illuminated” project and the messages they want to send with their films, which will be projected on the old prison wall facing Fairmount Avenue.

We’ve agreed to withhold their last names and not to discuss their crimes, per Pennsylvania Department of Corrections policy.

Donyea P., 28, ‘Big Boy Shoes’

In the first seconds of the minute-long animation “Big Boy Shoes,” a red theater curtain pulls back to reveal the word “drama.”

That’s how animator Donyea P. describes his upbringing: “born into drama.”

He’s spent more than a decade behind bars and he’s used a lot of that time to think about the legacy of abuse he said he inherited at birth, as well as the kind of mark he wants to leave behind.

How people react to the cards they’re dealt with is an idea Donyea tries to explore in his animation.

“I just wanted to be sure that I explained how a person can commit to a crime or wrong — how a hurt person can hurt people,” he said.

In retrospect, Donyea suspects a poor relationship with his mother is probably what prompted him to run away at the age of 14, made him susceptible to negative influences that introduced him to a life of crime, and led to his incarceration at 16.

Still, Donyea doesn’t want to let the “baggage” of his childhood define him.

“Even though I came from whatever or I may have done whatever, I can be something other,” he said. “When I speak of legacies, it’s about understanding that it’s not maybe how you started or what you’re going through, but how you finish the fight.”

Donyea said animation is one of the hardest things he’s ever tried. “You have to draw thousands of pictures for one minute.”

But he hopes his work will dissuade young people experiencing difficult home lives from heading into the wrong direction in life.

“You’re not your last mistake,” he said. “Your life shouldn’t be based upon your last mistake.”

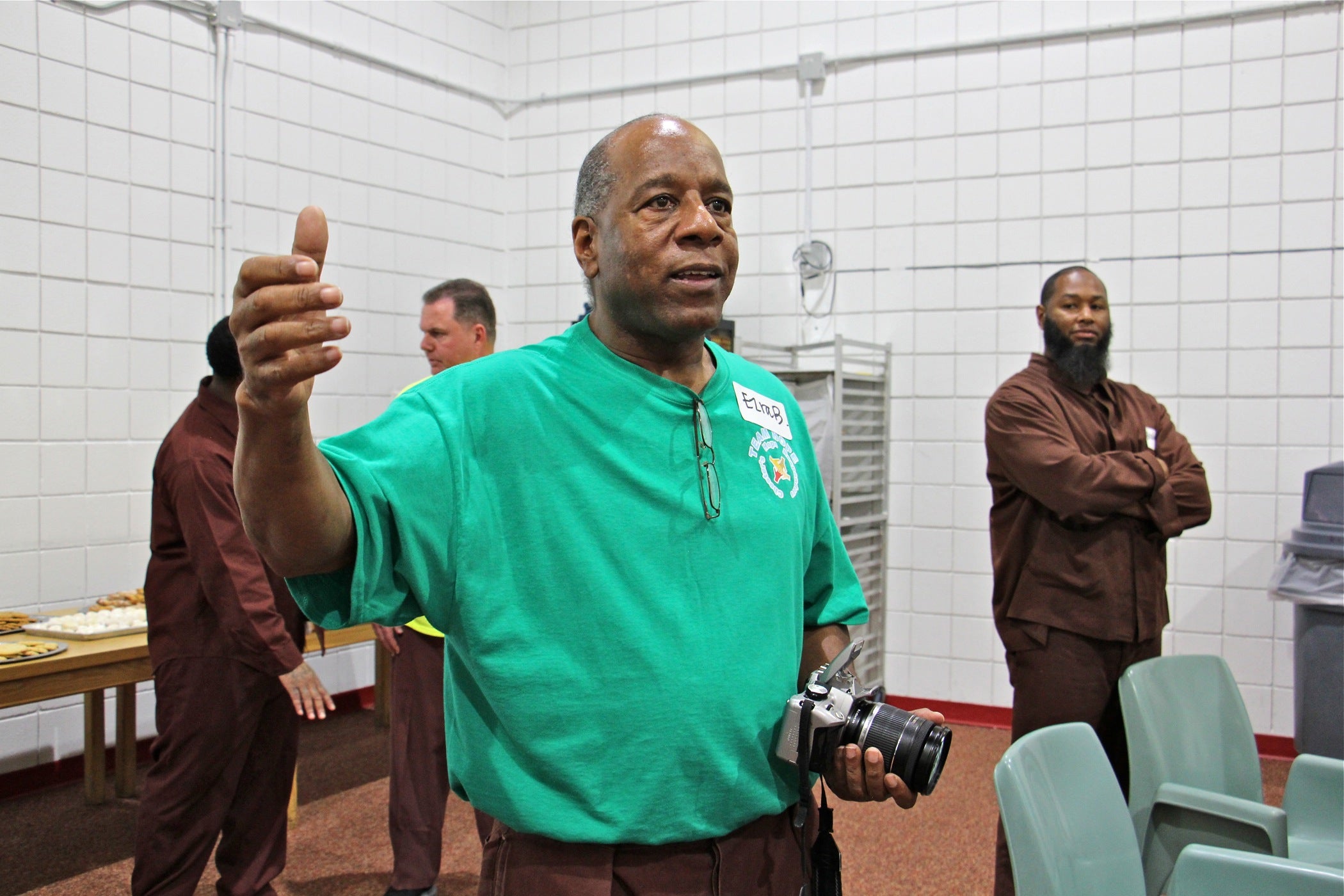

Ezra B., 63, ‘Phoenix’

While incarcerated, Ezra B. has tutored fellow inmates in Microsoft Suite, been heavily involved in the prison’s audio-visual department, and acted as a head coach in an anti-violence project.

“There is a lot of service that can be done inside of prison, although most of the community don’t know,” he said.

Ezra’s animation, “Phoenix,” tries to show how a person can change in their time behind bars and it mirrors his own life.

Viewers see the white outline of an unnamed protagonist, whom they’ve followed since birth, kicked by a bodiless foot into a literal pipe labeled “school to prison pipeline.”

“Running the streets” from a young age, despite the strong role models he had at home who tried to “instill good values,” Ezra said he gave into peer pressure and turned to crime.

It wasn’t until after Ezra began serving a life sentence at 19 that he started to become the person he is today, he said.

The protagonist in his film also finds redemption behind bars, climbing steps labeled “tenacious,” “persistent,” and “determined.”

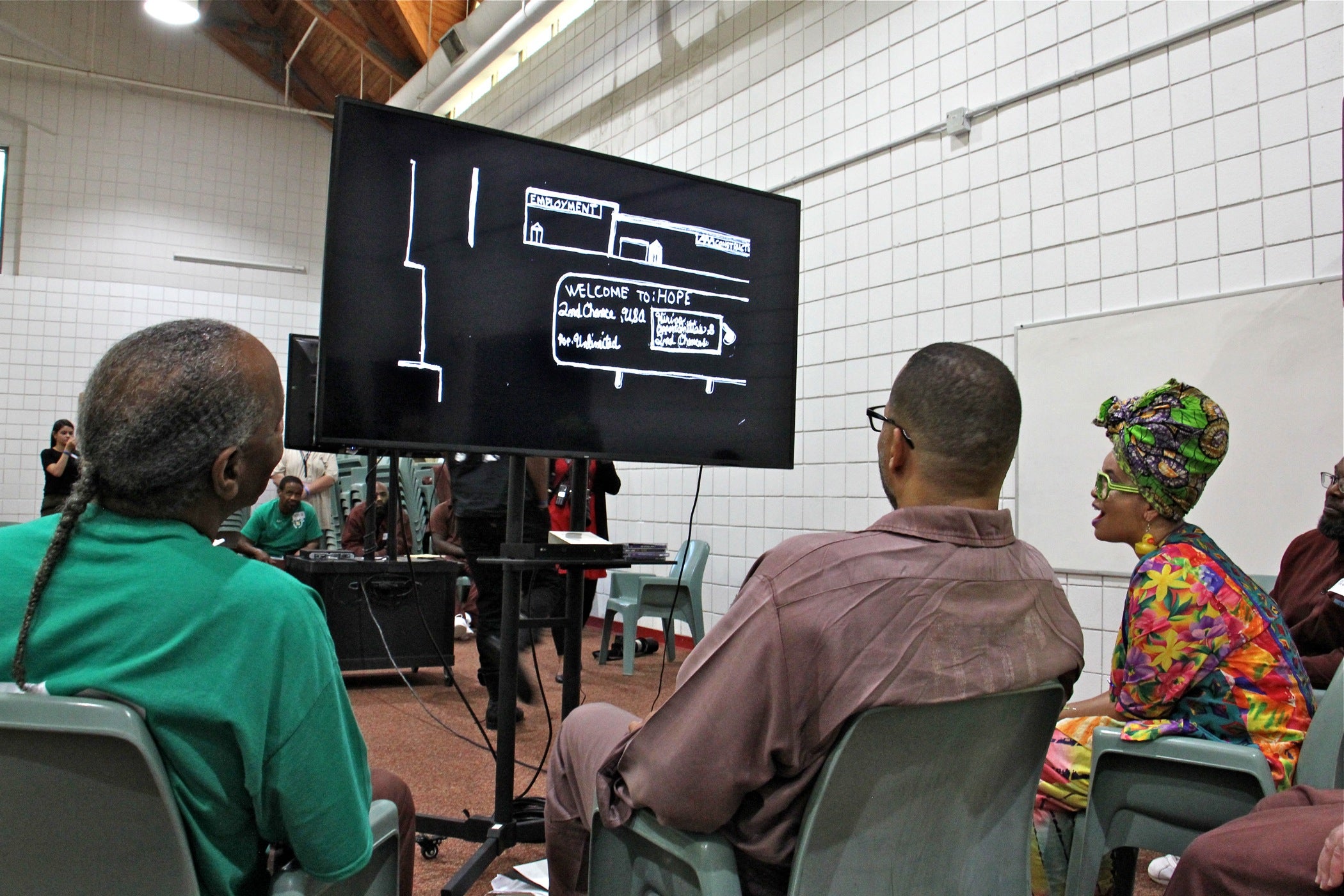

The final images are of a town named “Second Chance, U.S.A” and the image of a phoenix, presumably the main character.

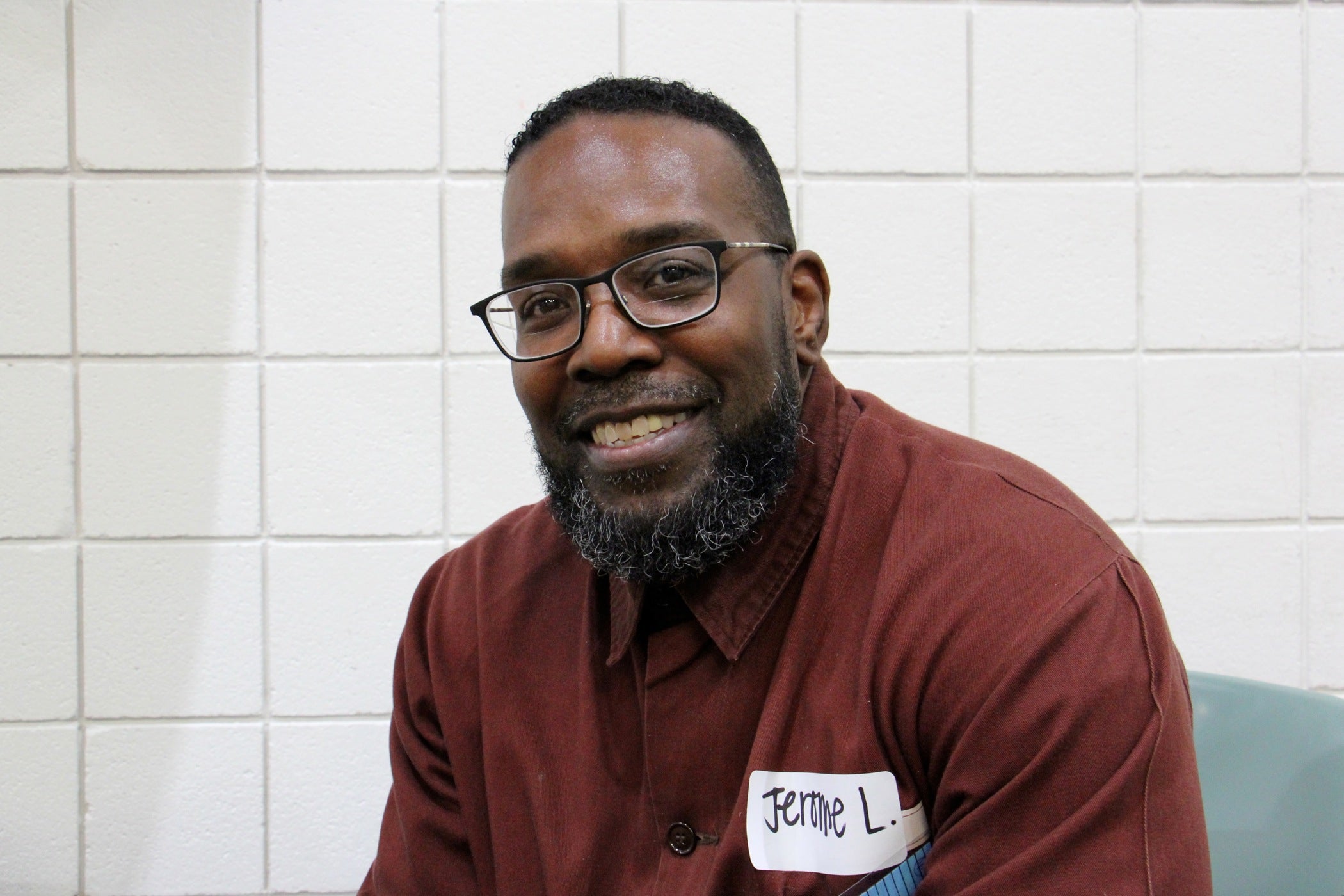

Jerome L., 55, ‘Justice’

Like his peers, Jerome also speaks to the idea that a person can be more than a product of their environment and how prison has helped him think about how to be a better person.

But as someone who has been locked up for almost 40 years, he also wanted to draw attention to how traumatic incarceration can be.

In one scene from “Justice,” the viewer takes the point of view of the protagonist heading to prison. The background is red and as a robed grim reaper guides the viewer into prison, the letters “PTSD” (post-traumatic stress disorder) flash over the prison entrance.

“It’s no different than a person going in the military and going to war and being in the army for two years, five years or 10 years – you know, a lot of them come back and suffer from PTSD,” he said. “Same thing with prison life.”

For him, the project was a way to point out how incarceration can inflict trauma of its own, making reentry hard for former inmates.

“It really gave me a way of trying to get my message out,” Jerome said. “I’m hoping I can get a voice.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.