After 50 years, funk album recorded in Philly finally debuts

The Nat Turner Rebellion recorded the blistering funk-rock-soul album at Philly’s Sigma Sound Studios, but it sat forgotten on a shelf for a half-century.

Listen 5:37

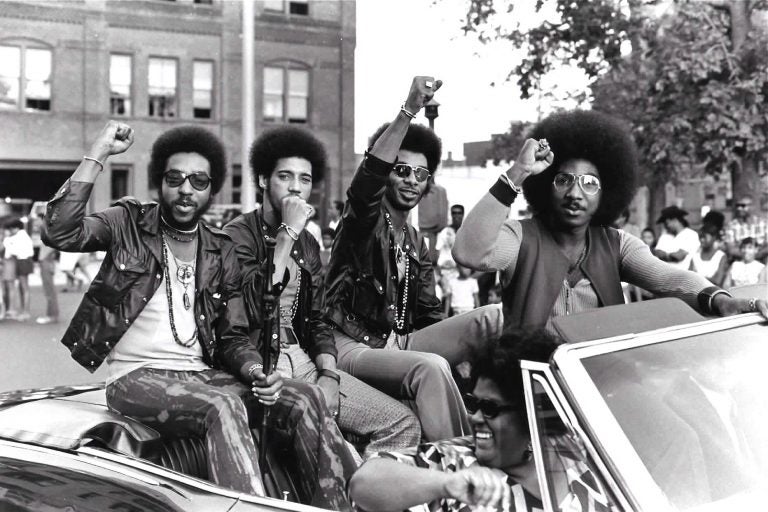

Members of the Nat Turner Rebellion ride in a parade during a Harambe Festival in Springfield, Mass., in the early 1970s. Pictured from left are Major Harris, Ron Hopper, Bill Stratley, and Joe Jefferson. (Courtesy of Reservoir Media)

In the late 1960s, Joe Jefferson of Petersburg, Virginia, was a drummer for hire, and he was good. He was in his 20s and had a lot of work.

Touring with Cissy Houston and her group Sweet Inspirations on the way to Vegas, he was waylaid in Philadelphia with a foot infection.

As he recuperated, he had a revelation: He didn’t want to play R&B anymore.

“I got tired of that. Tired. Tired. Tired. I got tired of beating somebody else’s drum. I wanted to beat my own drum,” he said. “I knew I had something. It was now or never – I either put something together, or I never will. I went home, back to Petersburg, and put together the Nat Turner Rebellion.”

Named after the 1831 slave uprising in Virginia — not far from Jefferson’s home town — that killed over 50 white people, the band was a blistering live act that toured the East Coast from Florida to Montreal.

“We were crowd killers,” said Jefferson. “You come to see one of our shows, you never forget the band.”

The band was fronted by four singers: Jefferson, Bill Spratley, Ron Hopper, and Major Harris trading lyrics, harmonies, and shouts. They were backed up by a seven-piece band with a horn section.

The outfit could slide from greasy funk (“Fat Back”) to smooth ballads (“Ruby Lee”), to psychedelic soul (“McBride’s Daughter”). They never strayed far from a heroic Sly Stone-like anthem (“Right On, We’re Back”).

“Vocally, the Temptations did it for us,” said Jefferson. “As for a rock band, the [Rolling] Stones did it for me. I was a Stones fanatic. But the soul of the Nat Turner Rebellion, if there was anybody, it was Sly and the Family Stone. We wanted to be Sly. Didn’t everybody?”

Bumps in the road

After proving themselves on the road, it was time to put the record on wax. In 1969 Jefferson and the Nat Turner Rebellion signed with Stan Watson at Philly Groove Records in Philadelphia.

That’s where the trouble started.

Watson had already scored a huge hit with the Delfonics, who put out smooth, sweet R&B with big string orchestrations (“La La Means I Love You”). Watson was looking to fill up his roster of talent.

“I never forget the day we went up to 52nd and Spruce, where he had an office. We auditioned for him,” Jefferson recalled. “That guy was finished. He could have gone home and changed his pants because he was done.”

After all the success of the Delphonics, Watson was looking for lightning to strike again with the Rebellion. But the two bands had little in common.

“He had an eye for talent,” said Jefferson. “The problem was, he had an eye for talent, but after that, it was a blind eye. He didn’t know what to do with people after he got them. That’s where we were.”

The album was recorded at Sigma Sound Studios in Philadelphia, but it was never released. Meanwhile, the band had its own internal problems and fell apart. The tapes stayed on the shelf for 30 years, until Sigma Sound shut down and all of its tapes were shipped across town to the audio archive at Drexel University.

At Drexel, they were dutifully cataloged and stored along with hundreds of other leftovers from Sigma Sound. But no one listened to them.

There they sat another 10 years until Faith Newman of Reservoir Media bought the rights to the entire Philly Groove Records catalog. She was most interested in owning a piece of the Delfonics and the girl group called First Choice, still valuable licensing assets.

The rest of the Philly Groove catalog came with the package, sight-unseen. Newman didn’t fully know what she had just bought.

“I went through boxes of paraphernalia from Philly Groove, and saw photos of the Nat Turner Rebellion,” said Newman. “Looking at these guys with afros and raised fists. Knowing that the biggest acts on Philly Groove were the Delfonics and First Choice, this was totally different.”

“Then I heard the music and was really intrigued,” she said.

Timeless themes

There was enough material on those forgotten tapes to fill a long-playing record with songs including “Tribute to a Slave,” “Plastic People,” and the title track “Laugh to Keep from Crying” (“I gotta laugh to keep from crying, I gotta try to keep from dying”).

“When you think about the discussions we’re having about race, still, the things they are talking about still apply,” said Newman. “All these years later, we’re still having this same dialogue.”

Newman faced the challenge of “re-releasing” a 50 year-old album that had never been released in the first place. But she worked with Toby Seay, director of Drexel’s department of art and entertainment enterprise, to pull together a package of releasable material.

The songs tell a story — of a push and pull of political expression; of a band finding its creative identity; and of a record label trying to shoehorn it into a marketing mold.

“We have songs that paint a picture of an industry, this struggle internally and with music industry marketing, and a story of a band in its place in time and its struggle in the late ‘60s civil right era,” said Seay. “Do we have message music, or do we sell records? Do those two things work together or not?”

Rebellious spirit abides

The Nat Turner Rebellion may have been his first music enterprise but it certainly wasn’t his last. Jefferson went on to be a successful songwriter, penning tunes for the O’Jay’s, Patti Labelle, and Tupac that appeared on platinum-selling albums.

He has mixed feelings about this record. For one thing, the Nat Turner Rebellion was best as a live act. Jefferson said the studio recordings did not capture what they could do on stage.

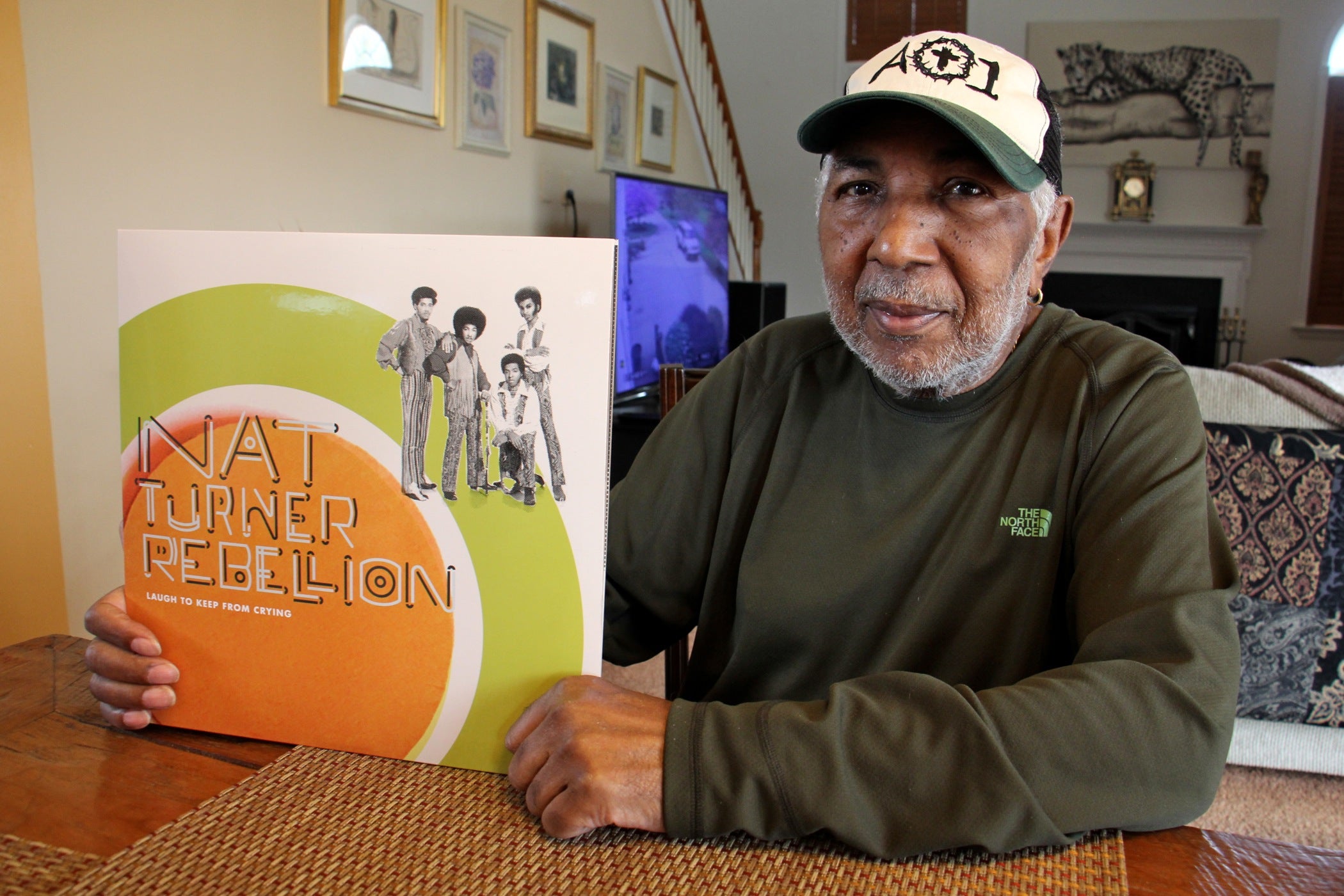

“I’m not unhappy about this album. I’m very happy about this album. I guess the thing that I’m most unhappy about is that my guys aren’t here,” said the band’s last living member,

The one thing that’s scared Jefferson is if the Rebellion were to rise again. As a staunch music industry survivor, he knows a hit record needs to be supported by live shows.

“Why didn’t they call me when my hair was black?” he said, taking off his hat to show a head of gray while sitting at the kitchen table in his Mount Laurel, New Jersey, home.

Still, Jefferson is certain he could put together a band that could fill Nat Turner’s shoes and satisfy fans newly hungry for a Rebellion.

But what would it mean?

“’Put the band back together.’ To me that’s just a sentence,” he said. “Are you really putting the band back together, or are you deceiving everybody? Is your heart really in the same place it was before?

“I don’t know if I want to do that. It might be a step back.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.