A Judicial Approach to Sex Trafficking, Prostitution- Delaware’s Sex Trade, Part 4

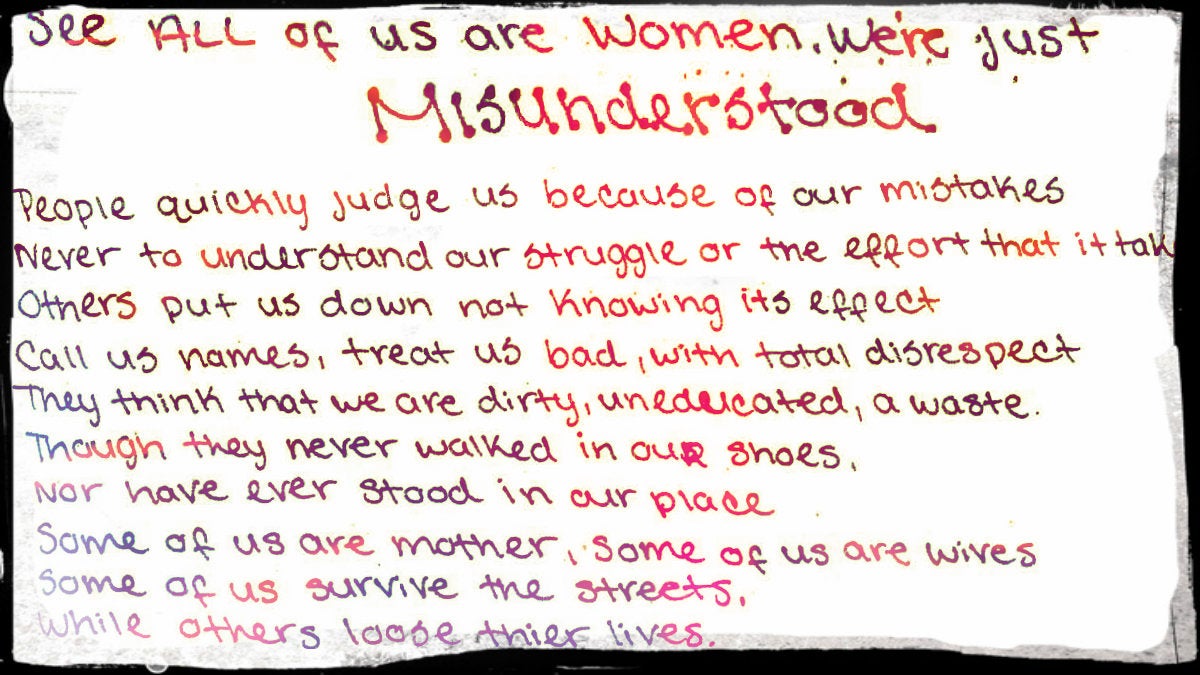

One of the women in McDonough's program wrote a poem about the stigma she's faced. (Courtesy of Mary McDonough).

For the past several months, WHYY’s Zoë Read has been interviewing experts about prostitution and sex trafficking in Delaware. WHYY will publish a chapter of the story each day of the week. Click here to read Part 1; The so-called ‘life’, click here to read Part 2; Advocating from the Ground Up and here to read Part 3; Advocates Work to End Trafficking.

A New Judicial Approach

Tammie, the sex trafficking survivor and recovering addict, is sitting in a courtroom—not because she’s in trouble with the law, but because she’s being rewarded for her hard work. She’s graduating from the courthouse program she partly credits to helping her get her life back together.

With a huge smile on her face Tammie practically gallops toward the well of the courtroom, her heavy shoes clonking loudly. She says she’s excited that even her prosecutor attended the program graduation—something the judge says is a first.

The prosecutor hands Tammie a bouquet of roses, prompting her to cry tears of joy. Then her probation officer passes her a box of tissues.

Tammie, a Pittsburgh Steelers fan, also receives a team jersey and other memorabilia as a gesture for her hard work.

“When you looked at your friend and said, ‘See, they love me,’—it’s true,” the judge tells her.

The judge hands Tammie a certificate and hugs her.

When New Castle County Family Court Judge Mary McDonough first became a commissioner in the Court of Common Pleas she saw the same faces from the women’s prison on her video calendar.

She said the women faced similar charges—loitering for drugs, walking on a highway without a light, shoplifting. McDonough said she began to read between lines and figured out these women were likely involved in prostitution.

“The typical sanction at the time for those types of offenses was a fine. Generally, these women did not pay the fine and I would see them again for failure to pay the fine,” she said.

“So the revolving door of the criminal justice system would spin quite quickly. I would see these same faces over and over again for similar offenses, similar sanction opposed but nothing changing.”

Since 2012 McDonough has ruled what has since been dubbed the “trafficking court,” a program that serves women on probation, who at some point was possibly involved in prostitution. Similar programs have existed in other cities, such as New York City, for several years.

Leon, the UD professor, said her research also led to the state issuing the trafficking court, but that her research did not recommend it.

She said social services, like housing assistance, community mental health and legal aid, that are open to those seeking those resources are more beneficial than coercive institutions like courts.

“We have this idea that if you’ve been convicted of something or arrested of something you have such terrible judgment you don’t know what’s best for you and you’re not going to take advantage of opportunities to do things differently,” Leon said.

“And that’s an unfortunate and prejudicial way of looking at a group of people who have a lot of resilience and can ask for what they need, they just need us to shift our thinking in how to provide it.”

Leon said she hasn’t followed Delaware’s trafficking court since completing the research, but said she believes McDonough is an example of someone in the justice system who can make a change.

“I do think that Commissioner McDonough does, as an individual, do good work,” Leon said. “It is certainly better to have empathetic people in positions within the criminal justice system than not.”

However, she said court systems in general do not acknowledge the multi-faceted nature of sex work, and that women involved have different needs and backgrounds.

“For example, for some people, the increased surveillance of diversion programs is not worth the sanctions if they fail—some would rather just do their time up front,” Leon stated.

“In some prostitution court programs, everyone must participate in sexual abuse treatment, regardless of stated need (the program has an underlying presumption of victimization, and it also funnels out people not viewed as victims). In some prostitution court programs, everyone must participate in substance abuse treatment, regardless of stated need (as though people must be addicted to be involved in sex work).”

Others like Sclabach of Zoë Ministries say the court program is the only positive and proactive measure on the state’s behalf when it comes to sex trafficking and prostitution.

Women with any drug charge qualify for the program, but they might be disqualified if they have a felony conviction or if they have a violent history, depending on the circumstances.

The women meet with Women in Support of Health coordinators, a group that helps women involved in prostitution transition out of the life, a TASC drug and alcohol counselor and their probation officer.

McDonough also partners with Meet Me at the Well and Zoë Ministries if the women need extra services, like clothing or housing help.

A person can be terminated from the program, and they also can choose to leave if they want to. They are required by law to remain on probation, but the program itself is voluntary.

There usually are about 20 women in the program at one time.

“This is a population of women who enter the program with tremendous distrust of the system and it takes time to build up that trust and it takes time before individuals are going to open up about traumatic experiences in their life,” McDonough said.

Many of the women in the program suffered traumatic childhoods. A former participant was put into the life at 8 years old by her mother, who also was involved in prostitution.

“Tragically for a significant majority of the women in our program they have been victims of sexual abuse and often that occurred in their childhood,” McDonough said.

“If there can be real healing from that trauma of childhood abuse and neglect and the women realize they deserve to be treated with respect and dignity, something they’re not accustomed to receiving, then it’s like, the switch goes off.”

The women in the program must maintain sobriety, continue their mental health treatments if needed, show up to probation and parole on a regular basis, and prove they’ve made some sort of progress before they can be considered for graduation.

McDonough also wants to be assured the women have a safe, drug-free residence, a plan to support themselves financially or are attempting to get a job or GED.

The bare minimum for graduation includes three month’s sobriety, three months of compliance to reporting to probation and no new criminal charges in any jurisdictions. The average amount of time a woman stays in the program is between one and two years.

“The graduations really are a big deal for the women,” McDonough said. “Sometimes it’s the first graduation in their life.”

A woman can stay longer if they need to—Tammie was involved for five years.

Tammie was accepted into trafficking court after she was arrested for shoplifting. She said at first she used it as a “get out of jail free card,” but when she took it seriously it helped her get her life on track.

“Thank God for the Commissioner,” Tammie said. “She stuck with me for five years, and never gave up on me.”

Jeffrey Sytsma-Sherman, the senior social worker and case manager for TASC, which provides addiction and behavioral health services to the women, said he sees a drastic change from the time he first counsels them to graduation.

“We give them a bit of hope and hopefully a future where they’re not forced to go back on the street again,” he said. “They can do it, and a lot of times they know they can do it, but they don’t know how. So we give them the tools to do it.”

Katrina Banks, who leads WISH, helps connect women to mental health resources and helps them find housing—something McDonough said is of utmost importance.

“If a woman doesn’t have safe, drug-free housing the chances of her success goes down,” McDonough said. “If they go to these cheap hotels it really is a worry. Many, not all, but many do not have stable family support.”

Banks also helps the women get their GED, and connects them to career resources.

“It’s not easy for them to find employment, especially if they have charges, and if they can’t get jobs, if they have families, sometimes they revert back to sex work or other means of getting income,” Banks said.

WISH, which also did its own street outreach to women involved in prostitution, lost its funding in August after five years of providing employment, education and health services to women.

The program, which was led by Beautiful Gate Outreach Center, Brandywine Counseling and other groups, previously received funding from the state’s Office of Women’s Health. This year, funding was not available.

Tamika Cobb, Beautiful Gate’s executive director, said the women can still access some of the services by going to Brandywine Counseling.

“In terms of all the partners and participants, they truly are saddened it was not able to continue beyond its five years, but the good thing is there are still resources available,” she said.

The court system now is deciding the best way to offer the services WISH provided the women, but McDonough said it likely will be through Brandywine counseling.

The court also will make some other positive changes in the coming months. The program currently is post-adjudication, serving women who already have been charged and are on probation. Soon trafficking court will be a diversion program, so women can enter it after arrest, but prior to receiving a conviction, in order to divert the women away from the justice system.

The program currently is working with the Attorney General’s Office, and will receive volunteered expertise from other leaders of similar diversion programs in the nation. McDonough said the diversion program still is in the planning stages and doesn’t know when the transition will take place.

She said she hopes in the future the court system will be able to reach out to women when they’re much younger.

“What I wish we could do is intervene sooner, and quite frankly when they’re juveniles,” McDonough said. “I think the sooner the so-called system can intervene to provide treatment to give them a different path in life, the better chance of success. As juveniles that would be the most affective place to intervene.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.