A COVID-19 snapshot: How the Philadelphia region’s hospitals are managing

During interviews over the past week, as coronavirus cases continued to rise, officials said the tri-state region’s hospitals were up to the challenge.

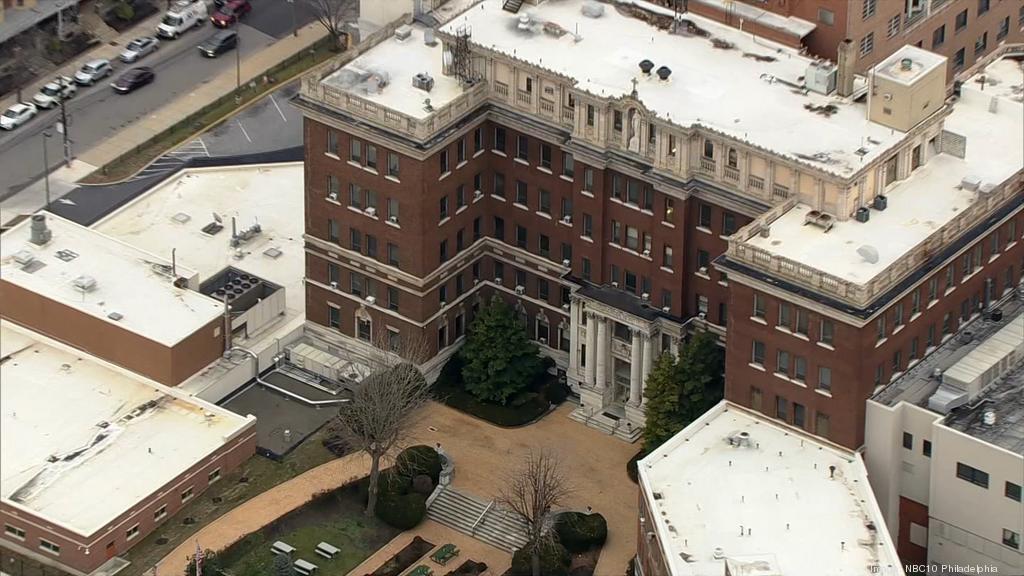

COVID-19 testing facility at Penn Presbyterian Hospital in Philadelphia. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Are you on the front lines of the coronavirus? Help us report on the pandemic.

Most hospital systems in the Philadelphia-South Jersey-Delaware region say they are able to manage the surge of COVID-19 patients thus far, though some hospitals have seen heavier caseloads than others.

In interviews with the WHYY News staff over the last week, officials of the region’s health systems offered a ground-level snapshot of what’s going on in the battle against the coronavirus.

As of April 20, more than 2,700 COVID-19 patients in Pennsylvania had been hospitalized, with more in the southeastern part of the state. More than half the isolation room beds in the state are still available, though the percentage of pediatric intensive care unit beds is running low, with only 24% free.

More than 7,500 people had been hospitalized in New Jersey, primarily in the northern part of the state, in counties neighboring New York City

More than 260 had been hospitalized in Delaware.

Setting up a COVID hospital

As of April 20, Temple Health had more than 200 COVID-19 patients, with most of them being cared for in the Boyer Pavilion on North Broad Street. That was something the health system learned from colleagues in China, said Robert McNamara, professor and chair of emergency medicine. Emergency department staff at Temple treat all who enter as if they could have the new coronavirus.

“We’ve solved the major logistical hurdle by having a COVID hospital,” McNamara said. “Fortunately, doctors can speak to each other easier than politicians can.”

The intensive care unit capacity was at 89%. All the patients needed oxygen, and around 14% of them were on ventilators. As of the week of April 13, the death rate was almost 4%.

Doylestown Hospital in Bucks County is employing a similar tactic, with a separate COVID critical care unit — what chief medical officer Scott Levy called “a hospital within a hospital.”

Staff, nurses and respiratory therapists working within that unit are dedicated only to that space and don’t share work with anyone else in the building, which minimizes any chance of cross-contamination or viral spread, Levy said. The unit itself is capable of holding 15 to 20 ICU beds currently. If need be, Levy said, staff could increase its capacity three- or four-fold by expanding the unit into areas typically used for elective procedures.

In the past week, Levy said, the staff has seen a reduction in the number of positive tests and diagnoses. At the same time, there has been an increase in the number of hospitalizations: about a 30% increase in patient volume that he hoped indicated the apex of the curve.

No shortage of beds

Trinity Mid-Atlantic’s hospitals have seen an increased need for ICU beds, but have been able to handle the surge thus far, said physician Sharon Carney, senior vice president and chief clinical officer. The system’s hospitals include Nazareth Hospital, Mercy Fitzgerald and Mercy Philadelphia. They also operate Mercy Home Health and Mercy LIFE.

Virtua Health actually had fewer patients at its five South Jersey hospitals than is normal at this time of year and expected to have adequate beds and equipment to meet an expected surge in late April.

Physician Reginald Blaber, the health system’s chief clinical officer, said measures to minimize the patient population — such as the state-mandated cancellation of elective surgeries and social distancing — were having their intended effect.

Back in March, the U.S. surgeon general recommended that hospitals suspend elective surgeries. Several medical associations, including the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the American Medical Association, agreed.

Hospitals in Pennsylvania have largely followed those recommendations, including the hospitals in the Penn Medicine system. That opened up a lot of room, said Patrick Brennan, the system’s chief medical officer.

Brennan said Penn Medicine had seen a particularly high number of COVID-19 patients at its Princeton Medical Center and Penn Presbyterian Medical Center. In some cases, staff had to convert other parts of the building, like a recovery unit, into a critical care unit. But the system still had beds available in the intensive care units and was prepared to take transfers from other hospital systems.

One problem, however, was a shortage of supplies. Brennan said Penn Medicine had moved equipment such as ventilators and other devices from one hospital to another to deal with shortages, and also had to reuse respirator masks by drying them for several days or decontaminating them with ultraviolet radiation or hydrogen peroxide. That started as a pilot program at one unit at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, but will move to other units. Brennan said the system was looking at a large-scale mask-decontamination system from a company called Battelle.

Well-stocked with protective equipment

Delaware’s largest hospital system, ChristianaCare, which operates hospitals in Christiana and Wilmington and a stand-alone emergency department in Middletown, was well below patient capacity. The system was also well-stocked with ventilators and personal protective equipment like masks and gowns, said president and CEO Janice Nevin. She credited coordination with the state and other hospitals for that.

The same was true for Beebe Healthcare in southern Delaware, according to president and CEO David Tam, who started on the job on March 16, days after Gov. John Carney issued a state of emergency.

The initial growth in COVID-19 cases was in northern Delaware, but recent days have seen an increasing rise in Sussex County, where Beebe is located. Workers have the ventilators, protective equipment and other items they need for now, Tam said.

Patients discharged to the ‘Rocky’ theme

The daily number of COVID-19 patients in the Main Line Health system’s hospitals has been steadily going up, but the average reached a plateau the week of April 13, and might have peaked, said chief medical officer Andy Norton.

“We think we’re at that inflection point right now, but it will take a number of days to know for sure,” Norton said.

With four hospitals, including Bryn Mawr Hospital and Lankenau Medical Center, Main Line Health serves Philadelphia and the western suburbs.

Norton said the system’s hospitals still had beds and rooms available, partly because patients with other conditions or elective surgeries were not coming in.

He added that Main Line Health had discharged more than 300 COVID-19 patients so far and that the numbers were encouraging. If patients came from nursing homes or group homes, that’s where they returned, though there was also space at Bryn Mawr Rehabilitation Hospital for patients who did not require intensive care, but needed space to recover before going home. Clinicians were following up with discharged patients.

The hospitals were playing the “Rocky” theme song as COVID-19 patients were discharged, to boost staff morale and that of patients — a kind of signal that people were recovering and can get better from the illness.

Concerns for patients who delayed non-COVID care

Scott Levy, Doylestown Health’s chief medical officer, said he was looking ahead — to patients who did not have COVID-related conditions, but were delaying or avoiding necessary care.

“What we saw in the first week or two of this was a significant decline in medical issues unrelated to COVID, as people were avoiding the emergency room at all costs,” he said. “What we’ve seen since then, probably over the last 10 days, is a resurgence of non-COVID ER visits, with patients who chose 2 ½ weeks ago not to come.”

Those who choose to wait it out can sometimes get better on their own. But others, Levy said, suffer complications that make the eventual diagnosis even worse.

“People have been waiting with abdominal pain, and now they have significant GI bleeds or perforated viscus; people with chest pains are coming in, and they have a completed heart attack from 10 days ago, or a completed stroke when it’s too late for us to do any intervention. So we’re seeing a higher level of acuity, and that’s very unfortunate, because one thing you don’t want to see people do is be in harm’s way because of their effort to prevent themselves from getting sick.”

WHYY’s Nina Feldman, Mark Eichmann, Nicholas Pugliese, Hannah Chinn and Ximena Conde contributed reporting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)