Islands in stream or pipe dream?

Dec. 19

By Kellie Patrick Gates

For PlanPhilly

A member of a prominent Philadelphia family who has worked as an architect, a stock broker, and a small-scale residential developer wants to string a chain of artificial islands through the Delaware River.

The way Gardner Cadwalader sees it, the islands would not only create primo real estate for him and his unnamed partners to lease, they would solve three pesky local problems:

–Since the islands would be molded from the stuff dredged up from the bottom of the river during the proposed deepening of the shipping channel, they would definitively end the battle over where to dump the material.

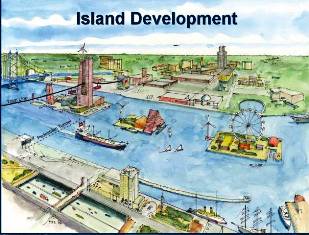

–The new hotels, homes and attractions he would build on the “archipelago” would help the city achieve its goal of revitalizing the riverfront. The islands would symbolize Philadelphia like the Opera House symbolizes Sydney, he said.

–There would be plenty of room for one or both proposed casinos, in a location far from any neighborhoods.

“It’s the most practical idea ever heard of in Philadelphia,” Cadwalader, 60, said.

But others – including representatives from some of the regulatory agencies whose approvals would be needed to undertake this project – don’t see anything practical about the proposal.

And neither does the office of Governor Ed Rendell. The deepening project is co-sponsored by the state and the Philadelphia Regional Port Authority, and Rendell has been among its biggest champions.

“I think it’s infeasible,” said B.J. Clark, the special assistant to the governor who has worked on the channel deepening project and has discussed the island project with Cadwalader. It has taken more than 20 years to do environmental studies and finalize the dumping sites for the dredged-up material, Clark said. “This would constitute starting all over again, which would not happen,” he said.

In an email response to Clark’s comments, Cadwalader noted that he first brought up the island idea much earlier in the process – in 1988. He got no response back then, but notes that the project sponsors were not yet in place.

The chilly reception his island plan has received has not cooled Cadwalader, who holds a masters degree in architecture from the University of Pennsylvania, rowed for the U.S. rowing team in the 1968 Olympic Games and has served on the boards of the Atwater Kent Museum and Fairmont Park Commission.

“Everybody is objecting to it, but that’s not at all a disincentive,” Cadwalader said matter-of-factly. “How many people objected to the Ben Franklin Parkway? Or to putting City Hall on Center Square? Anything that is a major change creates issues and questions.”

He hopes that the more Philadelphians learn about his project, the more support it will have. And all he really needs, he said, is one champion in a powerful place to bring the rest of the politicians and regulatory agencies on board.

“I understand all these ‘Nos,’ Cadwalader wrote in an email response to Clark’s comments. “Everyone who has said ‘no’ has good, solid documented and regulatory reasons. The merits and the benefits for everyone, however, of building the islands outweigh these objections for this once in a lifetime opportunity to ‘restore’ these famous and very useful islands and to make them the keystone for all our river front dreams on both sides of the Delaware River.”

Cadwalader calls his proposed string of islands Windmill Keys. The Windmill in the name is in honor of long-gone Windmill Island. It is also because of that former island and its also removed neighbor, Smith Island, that Cadwalader sees his project as a restoration of sorts.

Philadelphians used to spend summers picnicking and swimming on Windmill and Smith. The shade of huge, old willow trees provided a break from the heat – as did beer from the beer gardens. But in the 1890s, the islands were destroyed to make way for bigger, steam-powered ships.

None of the proposed islands would be the shape or size of Windmill and Smith islands, or sit in their exact location. Once one island before being cut in two so that ferries could more easily get to New Jersey, Windmill and Smith were long and narrow and stretched roughly from about Market Street to Bainbridge.

Cadwalader would like to eventually build 10 to 13 islands, stretching from the Ben Franklin Bridge to the Walt Whitman. Each island would have a slightly different character. Some would be largely residential, with condos and apartments. Others would have hotels, marinas and restaurants. One might feature family fun activities – an amusement park and a picnic grounds. And there would also be some natural areas that could be enjoyed by outdoor enthusiasts and river creatures alike, Cadwalader said. He pictures room for golf courses, marinas, an amusement park and wetlands and a nature preserve or zoo.

But he wants to start with two islands closer to the Ben Franklin – off the coast of the Penn Treaty Park. Each would be about 25 acres, and would be commercial and residential in nature, with a hotel, apartments and a casino – if SugarHouse or Foxwoods are interested. The islands would cost about $1 million per acre to construct, Cadwalader said. Because the state owns the riverbed land where the islands would go, he assumes he and his team (he says he has people lined up to participate once there’s some forward motion on his proposal) would build the islands under an agreement with the state. The state would then likely own the islands, he said, but his group would lease them and develop them, then lease the properties they build to others, who would operate them.

Philadelphia Regional Port Authority Chairman John H. Estey referred a call for comment to Clark. But to anyone worried that the islands would interfere with shipping, Cadwalader says they would be located on the far side of the shipping channel, but within the Pennsylvania boundary.

The islands could be built either by constructing a steel frame and filling that frame with the dredged materials, Cadwalader said, or by creating an earthen berm and filling that in. Either way, any island would have to sit and settle for at least a year before anything could be built on it, he said.

Artificial islands have been built elsewhere – off of Miami and in the Chesapeake Bay, and most grandly in Dubai. It is there that Al Nakheel Properties continues to develop several groupings of islands, some shaped like palm trees, others like a map of the world, and all home to luxury residences and hotels. Another faux island project, where the islands will take shapes of the sun, moon and planets, was announced in January. In May, Busch Gardens announced it would develop four theme parks on the islands. Donald Trump is also working with Al Nakheel Properties on a 60-story hotel and residential tower.

But here, there’s no supportive Emir. There is a considerable list of regulatory agencies that would have to sign off on Cadwalader’s project.

Cadwalader has not applied for any permits from those agencies. But last year, he spoke before a regional committee comprised of representatives from the regulatory agencies, the Urban Waterfront Action Group. The Group is affiliated with the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission and funded by the state Department of Environmental Protection. Its role is to advise would-be applicants on what permits a project would need and what it would take to receive them.

In short, group members were not encouraging.

“The way the proposal was shown last year, there is no way,” said Christoper Linn, senior environmental planner with the DVRPC and the coordinator of the Waterfront Action Group.

The project would need a federal permit from the Army Corps of Engineers and state permits from the state Department of Environmental Protection and possibly from the New Jersey equivalent as well, Linn said. And because the river bottom belongs to the state, an act of the legislature would also be necessary.

“Just generally, any projects on public trust lands are supposed to be water-dependent projects. Like a marina – you can’t build a marina in the middle of the state, it has to be on the water,” Linn said. But much of what was proposed before the Waterfront Action Group was islands as “a place for restaurants and hotels that could go anywhere.”

Linn, from the DVRPC, said the issues with the island proposal aren’t so much what would be used to construct the islands, but what they would be used for once completed. “If his proposal was an island made up of trees, and offered as ‘hey, wouldn’t this look nice and it would provide a foraging habitat for migrating birds,’ there may have been a slightly different reaction,” he said.

Linn sees Cadwalader’s proposed islands as “pedestals for highrise buildings” – buildings that would impact viewsheds.

But where Linn sees a viewshed, Cadwalader sees a vast expanse of emptiness that could be cozied up and brought down to a more human scale with some islands.

“Now it’s big, open and bland,” he said.

One member of the DVRPC committee, Delaware Riverkeeper Maya von Rossum, bluntly says that Cadwalader’s idea is awful. They would change the flow of the river and could create erosion problems where none currently exist, she said. And each one of the developed ones would become a whole new source of pollution, smack dab within the river itself.

But while von Rossum doesn’t support Cadwalder’s plan, she doesn’t dismiss it as impossible, either. In fact, she’s worried that Cadwalader is right-on with his assertion that the islands could provide a solution to the dredging problem.

“The islands are an excuse for the deepening of the river and vice versa,” she said. “It’s a way for that to move forward.”

The battle over whether deepening the channel – and what to do with the sediments removed as a result – has waged for years. A big part of the disagreement: The vast majority of the disposal sites are in New Jersey, but New Jersey doesn’t want to accept the material.

Rendell and New Jersey Governor John Corzine had worked out an agreement under which the spoils would all go to Pennsylvania – the state that wants the deepening done.

But Army Corps of Engineers spokesman Ed Voight said the agreement was reached when the Corps thought it would need new sites to handle the spoils. Since then, improved technology has lead to a better estimate of the volume, and the new estimates show all will fit in sites the Corps currently owns and uses for routine, maintenance dredging. Most of these are in New Jersey. One is in Delaware. And, Clark said, there is one site in southeastern Pennsylvania that will take rock.

This past summer, Corzine wrote a letter to the Corps asking that the governor’s agreement be upheld. Corzine disagrees with the Corps and Clark that no further action is needed for the spoils to go to the New Jersey sites.

“We still have issues to resolve with the state of New Jersey,” Voight said.

And Delaware has not issued a permit for dumping at its site.

Then there’s the money, which is not guaranteed. About two-thirds would come from the federal government, but no money has been set aside yet. Even before the current budget crises, the competition for funds was tight, Voight said. “There are far more Corps projects each year than money to build them.”

Voight says the single biggest variable in cost is the distance that the dredge materials must be moved, which is why the disposal sites are right along the water.

Clark, who expects the deepening work to begin in the summer of 2009, said he could not respond to Cadwalader’s assertion that using the dredged materials to build the islands would save money, because all he’s ever seen are sketches of what the islands would look like, not a cost analysis. “With all due respect to Mr. Cadwalader, it’s not a scientific proposal,” he said.

The sites where the Corps plans to put the materials dredged up in the deepening project already receive dredge materials from the routine, maintenance dredging of the river. Clark said the material is handled carefully. First, the water is allowed to run out of it, and this is returned to the river. Then, any polluted material is isolated and “properly contained.”

The vast majority of the dredge spoils can be used in construction projects. Cadwalader could try to get permits to use spoils that have been properly de-watered and examined for contaminants, Clark said – although he was pessimistic about Cadwalader’s chances for getting the necessary approvals in that case as well. “Building an island in the middle of the Delaware is a pretty big deal,” he said.

Cadwalader isn’t interested in building islands with dredge material that he would have to pay to move from the dumping sites. The economics of his proposal only work if the Corps brings the material to the island locations, he said.

“How could I not try to win over everyone to build these islands?” he said in an email. “The opportunity to use all that building material for the islands will never be in front of us again.”

Cadwalader said he’ll keep trying to convince the hoard of skeptics. He plans to reach out to the regulatory agencies, the governor’s office, and Pennsylvania’s U.S. senators early in 2009.

Contact the reporter at kelliespatrick@gmail.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.