ZCC gets “smart” about new way to zone

Feb. 27

By Matt Blanchard

For PlanPhilly

Selling the SmartCode to Philadelphia is a little like selling ice water to the Eskimos. Except that in this story, the Eskimos might be wise to place an order.

The SmartCode is the closest thing the zoning profession has to a social movement. It’s a model code, just about 56 pages long, that’s designed to be a national template for a whole new paradigm of zoning. Like an “open source” software code, it was created by the collaborative volunteer effort of architects and lawyers across the country who offer it free of charge. They share one mission: Ending forever the use-based, 1960s zoning codes they say foster suburban sprawl.

The goal is to zone based on neighborhood character, not merely use. The dream is to make America safe for pre-WWII “traditional” neighborhood forms by building those forms into zoning. It’s already been adopted by 20 municipalities, and forms the basis of Miami’s new zoning code. As it happens, a major inspiration for this revolution is Philadelphia.

“I am a Philadelphian,” SmartCode editor Sandy Sorlien told the Zoning Code Commission at its Wednesday morning meeting. “This code is influenced by my love of Philadelphia neighborhoods. It’s based on analysis of neighborhoods very much like those of Philadelphia: walkable, mixed-use, compact, and full of diverse housing types.”

But isn’t Sorlien just carrying coals to Newcastle? If Philadelphia already looks like the SmartCode, what do we need it for?

We are melting

Philadelphia’s current code is what we call Euclidean, or use-based. With categories like “Residential” and “Commercial”, it’s quite good at separating uses that might not get along.

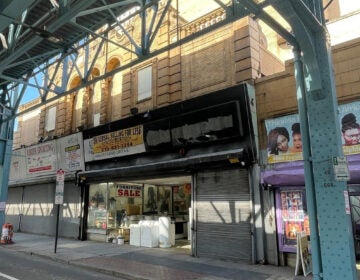

Yet Sorlien says we must ask more of our code. Each time she sees a gas station or drug store blast a half-acre of pavement into an otherwise urban block, or a rowhouse that meets the street with a big blank garage door, she says even Philadelphia’s urbanity is “melting away.” A drive up Ridge Avenue, she says, or down South Broad, lays the situation bare.

“The chipping away at the urban fabric is happening lot-by-lot,” said Sorlien, who lives in Roxborough. “Suburban patterns are coming into the urban fabric. Even in Philadelphia, it’s an emergency… As someone who loves Philadelphia – and people tell me it’s sickening how much I love Philadelphia – I wouldn’t have brought the code here today if I didn’t think we needed it.”

Sorlien, a former photography professor at Penn and the University of the Arts, believes the code’s resemblance to Philadelphia will only ease the process of tailoring it to our city. Miami’s effort to adapt the code is expected to end just three years after it began, which would be a national speed record for code re-writing and re-mapping.

How it works

The SmartCode grew out of New Urbanism, a movement to reform city building in America generated by frustration with the social and experiential wasteland of suburban sprawl.

Associated with the Florida firm of Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, the movement’s first physical success was the famous neo-traditional town of Seaside, Florida in 1980.

But out in the real world, New Urbanists quickly found their beloved traditional mix of housing and shops was forbidden by use-based zoning. If Main Street America burnt down one night, rebuilding it was essentially illegal. As Sorlien explains: “Very early on, New Urbanists realized that if we don’t change the zoning, we won’t get anywhere.”

The SmartCode is based on form: the size and mass of buildings, and all the ways those buildings create the “outdoor room” of the street.

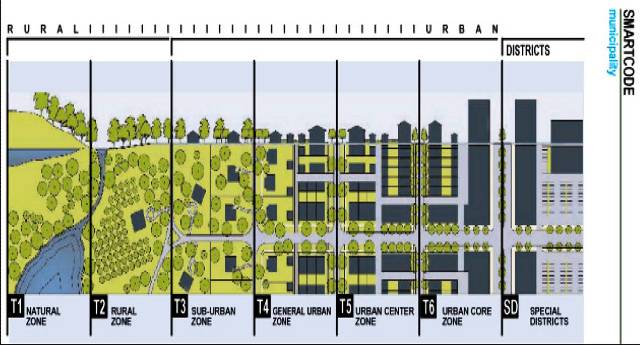

Since form is tough to discuss, SmartCode employs a concept borrowed from ecology: the Transect Zone, or cross-section. Just as you might imagine a cross section of natural land would reveal different habitats at different altitudes or temperatures, architect Andres Duany imagined a cross section of the urban environment would reveal different habitats we humans enjoy, from rural village to Center City skyscraper. Each habitat, in turn, has distinct qualities Duany sought to describe. The SmartCode is that effort.

The habitat approach is obvious in the code: Rather than R9s and C5s, you get Transect Zones 1 through 6.

T1 is natural land, either agricultural land, pristine preserves, or city parks like the Wissahickon gorge. T2 is rural and T3 is essentially suburban. Most of rowhouse Philadelphia qualifies as T4 and T5, with Center City’s office district being T6. Rather than assigning specific uses to specific sites, each of the transects defines which uses are allowed and how they should interact.

Under Philadelphia’s use-based code, for instance, the owner of a corner building might have the zoning for a ground-floor sandwich shop, but won’t use it. Across the way, a second owner may be desperate to open a sandwich shop, but she doesn’t have the zoning. The net result? No sandwich shop.

In form-based codes like the SmartCode, all corner sites in a T4 (General Urban) neighborhood might be green-lighted for sandwich shops. But in addition, the code might require a grand corner entrance, a stoop, fence or side yard, or that the upper floors be housing. The net result here is sandwich shop – along with an attractive streetscape to stroll while you eat it.

Transportation, economic development, open spaces and historic preservation can all go into a form-based code. To see all those pistons firing at once, check out www.miami21.org

Smoke signals

Because the SmartCode starts with the street experience, Sorlien argues its adoption will make it much easier for Philadelphia to achieve the “contextual” zoning and “commercial corridor” resuscitations that zoning reformers desire. It could also make it easier to preserve the historic streetscapes that draw in tourists and new residents.

It is not impossible to accomplish these goals with the use-based zoning Philadelphia has now. But New Urbanists say that’s a little like composing a postcard with smoke signals. If you want to send a postcard, why not start with the postcard?

“You can get walkable zoning into a use-based code, but the amount of brain damage to do it, and the cost, would be crazy,” Sorlien says. “In a place like Philadelphia, it would take so little adjustment to make the SmartCode fit.”

While city planners may be more comfortable with the old paradigm, Sorlien urges a fresh start: “Even people who’ve worked with this code for 40 years know how dysfunctional it is,” she says. “In my opinion, it’s time to just start over.”

Contact the reporter at blanchard.matt@gmail.com

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.