Philly school board votes against two charter renewals — a major blow to heralded reform effort

For the first time, the School District of Philadelphia’s Board of Education has voted to convert two charter schools back to district control.

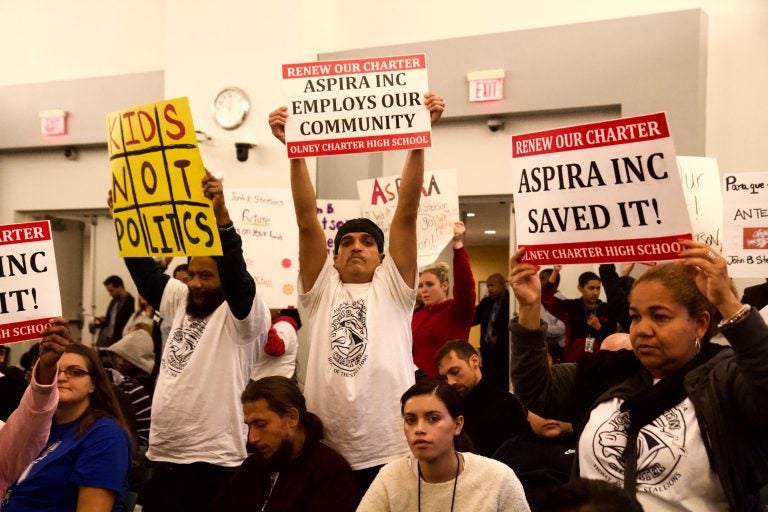

Students and parents show support for ASPIRA Charter Schools at Olney and Stetson at the Philadelphia Board of Education meeting on October 17. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

For the first time since it began turning neighborhood schools over to charter operators, the School District of Philadelphia’s Board of Education has voted to return two of those schools back to district control.

After years of deliberation, the board voted 8-1 Thursday night to not renew the charters of ASPIRA Charter School at Olney and ASPIRA Charter School at Stetson. The schools — which are both run by the North Philadelphia nonprofit — can appeal the decisions to a state board and continue operating in the interim.

If they fail to win those appeals or any subsequent lawsuits, the charters will officially dissolve and the district will resume control.

That prospect left some Olney and Stetson community members outraged. Many said the school, while not perfect, had made major strides under ASPIRA’s management.

“Olney will go to the way it used to be and it wasn’t great,” said Doris Thayer, who attended Olney High School when it was under district management and now has children there.

“If y’all failed me, y’all gonna fail them by letting ASPIRA out,” she added.

While some school board members expressed agony over the vote, most decided that ASPIRA had too many signs of organizational rot and had not produced the kind of academic improvement necessary to earn approval. Board chair Joyce Wilkerson was resolute.

“This school is not getting it done,” said Wilkerson. “I can’t endorse continuing a school that is failing the academic aspirations of children.”

John B. Stetson Middle School and Olney High School were given to ASPIRA in 2010 and 2011 respectively, as part of the district’s Renaissance Schools initiative, which ultimately affected 19 other schools. District leaders hoped new charter management would revitalize some of its most chronically underperforming buildings.

The district quietly stopped these conversions in 2016 without saying whether it will ever revive the program.

Stetson and Olney aren’t the first Renaissance charters to be recommended for non-renewal by Philadelphia’s Charter Schools Office, but they’re the first to receive an official non-renewal vote from the board.

It’s taken more than three years — and two governing bodies — to get to this place.

The Charter Schools Office (CSO) first recommended Stetson and Olney for non-renewal in early 2016, citing academic and organizational issues with the schools. Specifically, the CSO claimed ASPIRA improperly used funds earmarked for some of its schools to guarantee loans that had nothing to do with those schools.

ASPIRA’s attorney, Ken Trujillo, testified before the now-defunct School Reform Commission in 2016, asking for time to sort out the organization’s financial woes.

After several delayed votes, the SRC did eventually vote, in late 2017 to hold non-renewal hearings on Olney and Stetson. Those hearings sat in bureaucratic limbo for years.

Finally, in March, the district held non-renewal hearings, after which an officer found that Olney and Stetson hadn’t made enough academic progress to keep their charter status and that the schools had “failed to comply with generally accepted standards of fiscal management.”

On Thursday, Philadelphia’s Board of Education, which has been in power since replacing the SRC last summer, voted to certify the officer’s non-renewal recommendation.

That does not necessarily mean Stetson and Olney will revert back to district control. As with all unrenewed charters, the leaders of Stetson and Olney can appeal the vote to the Charter Appeals Board, which remains comprised of mainly appointees of former Gov. Tom Corbett. If the CAB upholds the Philadelphia board’s decision, Stetson and Olney could sue in state court.

Adding another layer of complication to this saga, ASPIRA is already suing the school district and school board in a separate case. That suit, filed last month, says the district unfairly shut ASPIRA out of the entire non-renewal process.

Some of the district’s concerns revolved around how ASPIRA spent money earmarked for its schools, which are distinct legal entities. But ASPIRA alleges that the standard non-renewal process provided little room for the organization, writ large, to explain itself.

Lingering facility concerns for SLA

Thursday’s board meeting came one week after district officials announced temporary homes for students from Benjamin Franklin High School and Science Leadership Academy, who will not return to their regular building until January due to ongoing construction and asbestos abatement.

Superintendent William Hite had said SLA students would split time between the district’s center city headquarters and space at Rodeph Shalom, a nearby synagogue.

Shortly thereafter, the synagogue, said it never agreed to that plan. Both parties say they’re trying to negotiate an agreement, but there’s been no update since last week. As of now, SLA students are not fully back in physical classrooms.

The district approved three amended contracts Thursday night related to the ongoing construction at Franklin. Combined, the contracts will cost the district $192,217.

Another charter, another legal drama

The school board also voted Thursday to renew the charter of Mathematics, Civics and Sciences Charter School (MCSCS), which is wrapped up in its own legal drama.

Earlier Thursday, the non-profit Education Law Center sued MCSCS on behalf of a parent who said her child was illegally refused admission.

The complaint alleges that the school’s CEO and founder, Veronica Joyner, told the parent that MCSCS could not enroll her child because the child has an emotional disability. Joyner, the complaint says, then gave the parent advice on how to get rid of the child’s special education status.

Joyner, however, says the entire case is based on a misunderstanding.

MCSCS did not think that the child had actually been accepted through the school’s lottery, Joyner said. Her advice to the parent, Georgette Hand, was based on the assumption that Hand wanted guidance on how to deal with the school district’s special education staff, Joyner explained.

Upon receiving the lawsuit, Joyner said, MCSCS asked attorneys from the Education Law Center to provide proof of admission. Joyner said the attorneys never sent that proof.

Today, when a reporter sent her that proof, Joyner said the school must have made a clerical error. She said the school would gladly admit the child now that it had proof of its own decision to admit the student.

“It’s a simple misunderstanding,” said Lewis Small, the school’s attorney.

Small called the lawsuit “unnecessary” and “ridiculous.”

ELC attorneys said they proof they shared with reporters today was sent to Joyner and MCSCS weeks ago. They received no response, they said, which is why they opted to sue.

“Despite many attempts to negotiate over the past five weeks, it took filing a lawsuit to get a substantive response from Ms. Joyner and Mr. Small,” said ELC attorney Margie Wakelin in a statement.

Joyner said her school serves plenty of special education students and does not discriminate.

The lawsuit notes that six percent of the charter school’s students receive special education services, well below the district-wide mark of 18 percent.

Despite the eleventh-hour appearance of a lawsuit, the board decided to approve a new, five-year charter term for MCSCS. The agreement was laced with strict conditions, according to Christina Grant, who heads the district Charter Schools Office.

For instance, Grant said, the CSO will appoint a “special education master” that will overhaul the charter school’s special education policies and keep a close eye on the school’s adherence to federal special education law.

If MCSCS does not comply with these new policies during its next term, Grant said, the CSO could move to revoke the school’s charter before five years is up.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.