How will our waterfront develop?

July 23

By Matt Blanchard

For PlanPhilly

Suddenly the options are clear. No longer is the waterfront’s fate a foggy future prospect. No longer is it just about casinos.

Two starkly different visions for the entire corridor have emerged. And with 1,000 acres of prime development land along the Delaware hanging in the balance, these two visions are bound to collide.

Developers have proposed at least 23 high-rise buildings to line the riverfront, most between 20 and 40 stories tall with massive parking garages. Advertised as “luxury” communities, critics call this wall of proposed construction “Miami Beach on the Delaware.” To see the details, click here.

Now Penn Praxis director Harris Steinberg has unveiled a second vision. Early sketches of a waterfront developed with community input were released on Monday morning click on pdf here. They’re the first specific proposals for what could be the city’s most important urban planning effort in 50 years.

The Praxis vision would take the two largest chunks of riverfront land and create two new neighborhoods, one in South Philadelphia and another stretching along Northern Liberties, Fishtown and Port Richmond. The existing landscape of huge sites, such as the waterfront WalMart, would be broken up with a web of new streets. This denser urban fabric could then sprout a cityscape of human-scaled homes, shops and parks, drawing the vitality of Philadelphia’s existing neighborhoods down to the river’s edge. It’s not Miami Beach, but rather Rittenhouse Square, that Praxis envisions on the river.

Which vision will win out? That depends on how hard civic leaders are willing to fight the prevailing political reality and make the Praxis plan into law.

Just such a group of civic leaders assembled to view the sketches on Monday: the Central Delaware Advisory Group, a task force of community activists, politicians, bureaucrats and planners assigned by Mayor Street to oversee the Praxis planning effort. Though their response was muted, commitment to the plan seemed solid.

“If the choice is between going to war on behalf of these proposals or bowing to the political realities, I say go to war,” said advisory group member Matt Ruben of Northern Liberties. “I think we need to make it a major issue for the general election … There will always be forces against it, but if you don’t stand firm for what you want, you won’t get anything.”

The Southern Section

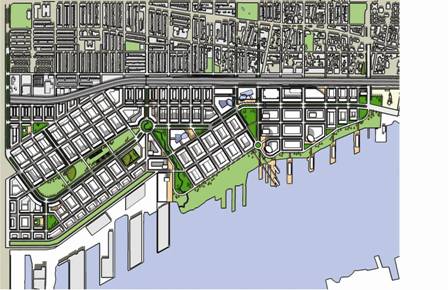

Above is a plan showing the South Philadelphia waterfront as it is today. Narrow neighborhood streets come to a halt at Interstate 95, south of which the scale balloons to accommodate automobile-dependent, big-box retailers like WalMart, visible in the dead center of the plan, and Ikea, visible to the left.

In this southern segment, Steinberg sees 325 acres of developable land, an area roughly an eighth the size of Center City. The Praxis plan would lay a new street grid of low to mid-rise housing, seen in yellow. It would also make Columbus Boulevard into a real urban boulevard, as well as providing a riverfront park on the WalMart property, seen in green. Note also the four greenways connecting the river back into Pennsport.

Steinberg jokes that the rigid-looking boxes of the image above make it resemble “a new piece of China.” Yet the image provides more detail of just what this new South Philadelphia neighborhood could look like, with details such as a baseball field, and the wiggly line of a reconstructed stream. Note that the port facilities remain untouched. In fact, Steinberg speculates that the port could serve as an “anchor institution” for the neighborhood, much as the University of Pennsylvania does for West Philadelphia.

The Northern Section

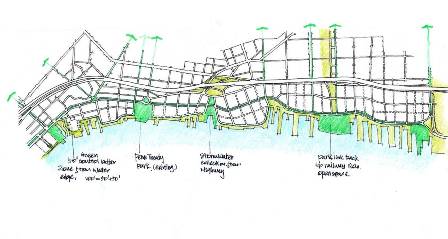

This image above shows vast amount of undeveloped riverfront terrain in Northern Liberties, Fishtown and Port Richmond. Altogether, it’s more than 400 acres. Penn Treaty Park is the green square to the left of center. Allegheny Avenue is the last wide street to the right.

Focusing first on green spaces, the Praxis plan calls for a “necklace” of five parks, starting with (from left to right) the old city incinerator site at the foot of Spring Garden Street; Penn Treaty Park expanded with a Logan Circle-like traffic roundabout; a new green space at Aramingo Avenue to resurrect the memory of the old Aramingo Canal; a sizeable new park on the Conrail site in Port Richmond to include preserved industrial ruins such as the Ore Pier; and an expanded Pulaski Park to the north.

Around this necklace of greenery, Praxis envisions new blocks of Philadelphia neighborhood to reconnect the city to the river. Yellow areas indicate such development in a web of new streets.

The end result could look something like this: A belt of entirely new mixed-use neighborhoods, fronting the river and connected by a pedestrian-friendly grand boulevard.

The Boulevard

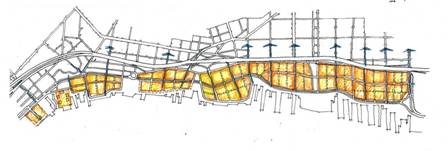

The exact width of the north-south boulevard would change at different points in its length, as would its course, sometimes running where Delaware Avenue is today, sometimes as Columbus Avenue, sometimes as Beach Street, and sometimes very close to the river along a yet-to-be platted right-of-way.

Yet the layout of the boulevard would be consistent, as seen above. Note the inclusion of a light rail line on the central median. Recent plans by the Center City District call for just such a line, shuttling across the city in the shape of a “T.” The top of the “T” would run along the waterfront from Oregon to Allegheny Avenue, picking up residents at grade level. The stem of the “T” would be a connecting spur running west down the center of Market Street to the office district around 20th Street.

Steinberg calls the light rail a “key piece” of infrastructure, because it will ultimately reduce the need for parking in a new riverfront district.

Reducing the need for parking reduces the overall size of buildings considerably, obviating the need for gargantuan garages that deaden the streetscape and consume land otherwise useful for river access. Right now, the city requires at least one parking spot per housing unit, adding considerable cost to developers. But it doesn’t have to be that way.

“It’s the cars that really drive height and mass,” Steinberg said. “If you have to park one car for every dwelling unit, suddenly these sites are overburdened with parking.”

Add a rail line, and the city may be able to reduce on-site parking requirements along the river. The garages go away, the traffic jams go away and the whole area moves one step away from Miami Beach and toward Rittenhouse Square.

A New Deal with Developers

The advantage of one public train over 20 private parking garages is emblematic of the case Steinberg hopes to make to the development community: If we all pull together, everybody wins.

“It’s in the development community’s best interest to support the kind of public investment in infrastructure that we’re proposing, because ultimately the value of their property will be increased,” Steinberg said.

Instead of packing their projects with private amenities, Steinberg hopes to entice developers to invest in the public amenities: Public parks, public river access, and lots of retail to enhance the public experience of the street.

But relying on the public realm requires a leap of faith. The riverfront today is mostly vacant land, with few guarantees that a real neighborhood with working public transit is about to appear. Steinberg will meet with developers and property owners on August 7 to make his case.

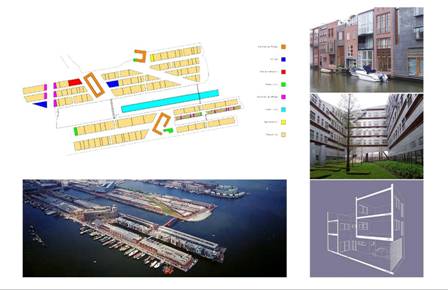

A possible point of controversy is Penn Praxis’ pier development guidelines. Right now, 35 and 40-story towers have been proposed for fairly narrow finger piers which extend into the Delaware. At Monday’s meeting, Steinberg called for a considerably less dense pier development scheme, such as the internationally-celebrated Dutch approach to building housing on piers seen below.

In the end, however, it is the city which must flex its muscle on the waterfront. It is the city, not the development community, which will ultimately slow the march to Miami Beach.

To that end, Steinberg is working with the City Planning Commission and Councilman Frank DiCicco to craft City Council legislation that will enshrine some of the PennPraxis design guidelines in law, in the form of a zoning overlay.

“What we’re seeing on the waterfront are pure economic forces at play,” he said. While developers have the right to seek the highest and best uses from their property, the city also has rights.

“The city has the authority to say, these are the rules; these are the lot sizes, this is how high the building can go, this the amount of density, this is the amount of parking,” Steinberg said. “This is all part and parcel of what a city does.”

—

Seeking to score an early victory on the river, Center City District head Paul Levy is putting together funds for a 4-mile bike trail along the Delaware River that could be open by the fall. Described as a “quick and dirty interim trail,” the route would make use of existing roads and paths, employing jersey barriers and other low-cost elements to shield pedestrians from the traffic. Levy said it would begin near Home Depot at Columbus and Tasker, extending north to Cumberland Street in Port Richmond, with the possibility of bicycle and skate rental kiosks along the length. Priced at around $300,000, the trail is more than an investment in recreation; it’s an investment in public opinion. “The more people out there using the riverfront, the more we have a constituency for public amenities on the waterfront,” Levy said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.