Zoning reform challenges await Philadelphia

May 19

By Matt Blanchard

For PlanPhilly

The fifteenth annual Congress for the New Urbanism convened in Philadelphia on Wednesday, drawing hundreds of progressive planners and architects to a city that needs them, perhaps now more than ever.

New Urbanism is a set of beliefs at the leading edge of city planning. The movement was founded in 1993 to fight suburban sprawl and build sustainable, walk-able, human-scaled communities – new places inspired by old cities like Philadelphia.

Today, the student has become the teacher. Industrial cities struggling to rebuild seek to recover the lost art of traditional town building embodied in the New Urbanism.

Governor Rendell acknowledged as much in a Friday address to the Congress, calling upon the assembled designers to expand their mission to address three issues over which American urbanism now stumbles: education, poverty and mass transportation.

“Unless we can deal with these issues, they’re as much a roadblock to New Urbanism as anything else,” Rendell said.

Other speakers included congressman Barney Frank, and architects Robert A. M. Stern, Denise Scott-Brown, and Peter Calthrope, as well as original New Urbanists Andres Duany and Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk.

For Philadelphia, the conference timing was auspicious, as the city faces urgent design challenges. On Tuesday, voters endorsed a referendum question to overhaul the city’s zoning code. This 624-page rulebook for development has been gathering amendments since 1963. Its outdated provisions leave Philadelphia without modern planning tools. It could take years to reform.

The power of zoning, for both good and ill, dominated a well-attended panel discussion on Thursday.

Typical zoning codes actually make it harder to build the kind of places Americans treasure, explained Peter J. Park, a respected planner behind code re-writes in Milwaukee and Denver.

“Conventional zoning often expresses a fundamentally negative attitude towards the city,” Park said. It does this by enforcing a rigid separation of residential and commercial uses that should be mixed, and by mandating a suburban-style set backs and parking requirements. For half a century, Park said, zoning codes like Philadelphia’s have make good urban neighborhoods harder to build.

Gesturing toward the image of a low-slung strip mall, Park said: “Even today, it is easier to do this type of development.”

That’s why cities like Miami, Boston, and New York are abandoning 1960s-era codes in favor of new, “form-based” codes that respect the existing urban fabric. They also replace thickets of legal language with simple line drawings that quickly show developers what can be built.

As Philadelphia embarks on its code re-write, Park and others predicted a lengthy and possibly contentious public process, with vigorous involvement by stakeholders in the government, the neighborhoods and the real estate community.

Failure is not an option. Many in the New Urbanist movement look to the revitalization of cities like Philadelphia as the cure to suburban sprawl, and an essential move in the fight against global warming. To them, bringing back older cities means bringing back energy-efficient mass transit, and absorbing growth that would otherwise end up populating the urban edge, consuming farmland and forests.

These connections between zoning, planning and the fate of the planet are a constant theme for New Urbanists, whose sense of historical mission is expressed in their choice of the word “Congress” for what is essentially a trade conference.

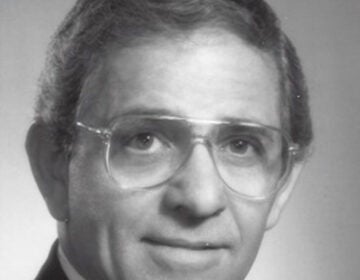

In a telling moment, Jonathan Barnett, director of Penn’s Urban Design Program, was awarded the Congress for New Urbanism’s “Athena Medal” before a crowd of hundreds in the vast plenary hall. His acceptance speech offered a short, self-effacing thanks and proceeded directly into frightening visions of America in 2050, where cities have “metastasized” into region-choking blobs of mega-sprawl.

“If intelligent people do not prevail, much of what we value about this country will be badly compromised,” he said.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.