Seeing Chester in watercolors

A photographer is rethinking his approach to documenting the city.

At Keystone Crossroads’ forums, we ask community members to do a free association exercise. We call out the name of a city, and ask them what words come to mind.

When we ask about Philadelphia, residents of other cities say words like, “Rocky,” “medical schools,” and “cheese steaks.” For Lancaster, they say “Amish,” “farms,” and “rural.”

And then we mention Chester. That’s when we hear words like “crime,” “failing schools,” “high drug use,” “dangerous,” and “poor.” (A few people also say “soccer” because of the city’s stadium.)

The people who call Chester dangerous aren’t wrong. in 2014, the city’s per-capita murder rate (the number of murders per 100,000 residents) was 88. For comparison, Detroit’s was about 43. Philadelphia’s was 16. New York’s was about 4.

But life in Chester is a lot more complex than that. And the way outsiders see Chester, or any city, isn’t necessarily how its residents see themselves.

Seven years in Chester

Justin Maxon learned this the hard way. He’s a photographer who has been documenting Chester since 2008.

Maxon first became interested in the community when he was an intern at The Associated Press in Philadelphia. His editor sent him to cover a fire in the city.

Maxon took a photograph of one of the distraught relatives of the victims.

The experience highlighted how journalists sometimes parachute into communities and capitalize on people’s grief.

“My photograph of a young Black women was in print the next morning in the Philadelphia Metro: half the page above the fold,” he wrote recently, reflecting on the experience. “I was proud; a young white man in his first college internship, with The Associated Press.”

He thought journalism was a public service, no matter what the topic.

“Eventually, I began to see the ignorance and contagious nature of my [mis] perceptions,” he says.

He met a family that day, and he started visiting them every week to learn more about their lives. Over several years, he met one family after another, snapping thousands of photos of them.

He gave those photos a pictorialist perspective. That’s an approach that emphasizes artistic expression over reality.

Maxon’s photos are black-and-white, and blurry, with hyperbolic features. They’re haunting. Almost otherworldly.

Over the last few years, these photos have been published in high-profile magazines like Mother Jones, and the blogs of Time magazine and The New Yorker. And organizations like the the Aaron Siskind Foundation and the Magnum Foundation have awarded Maxon funding to continue his work.

The only problem? Residents find the photos kind of creepy.

Maxon learned this after he started carrying around a book of his photos. He would stop people on the street in Chester, introduce himself, and show them his work.

Community members told him the photos were gloomy. Or gothic. He recently showed the book to a police officer who called it “spooky.”

In other words, the residents didn’t recognize their community in his photos. They didn’t feel like the photos represented them and their lives, Maxon says.

Maxon started to realize that his work, though well-intentioned, might be misrepresenting the community.

Race is an important factor here. Maxon is white, and his subjects are black. And in his photos, he tries to highlight important issues in the black community, including negative interactions with the police, unsolved murders, and rampant violence.

But the photos are so stark and surreal that they make it difficult for outsiders to relate to the people depicted, Maxon says. “I felt like my work was contributing to the creation of ‘the other,'” he says.

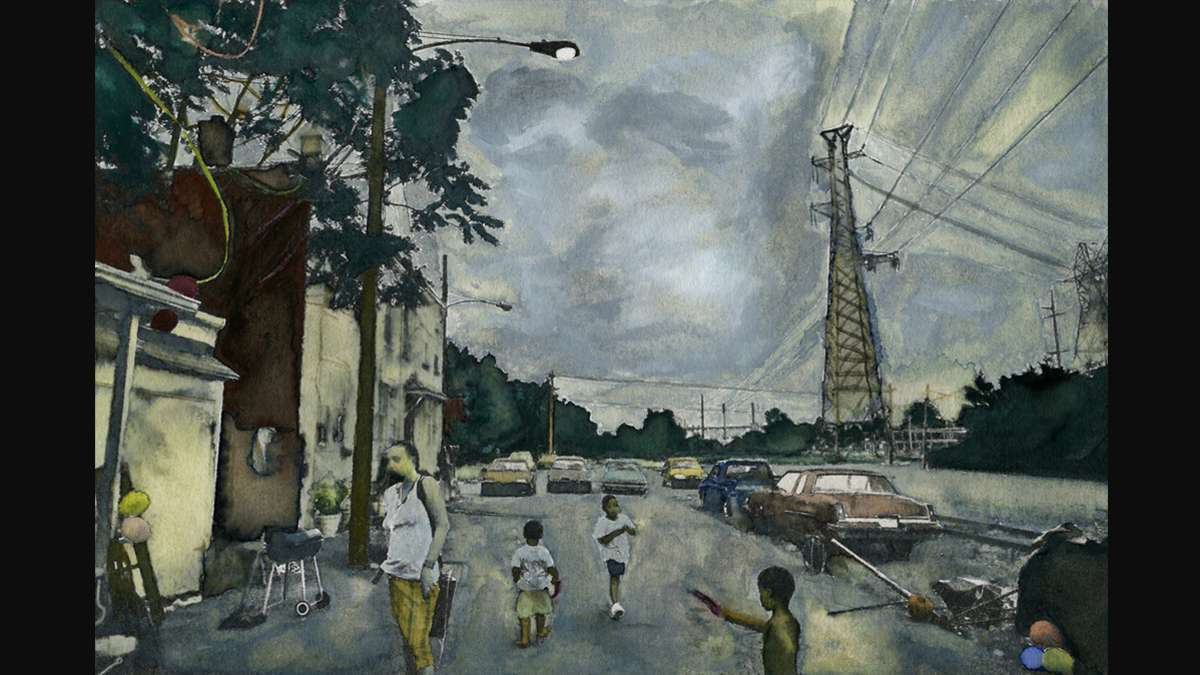

So Maxon decided to bring color back into his work. He has started painting his black and white images with watercolors. That’s something of a throwback, actually. Watercolors were used before film was invented to heighten realism and create images that were more relatable, he says.

You can see the before and after photos above.

Chester’s reality

Maxon has become close to many of the families he’s photographed. And he says the people who live in Chester face serious problems. The city’s public high school has a high dropout rate, for instance.

The rampant violence also leaves some residents traumatized. At one community meeting Maxon attended, a couple said they were so afraid of gunfire and stray bullets that they were sleeping in the basement of their home.

But the point is, the people who live in Chester are…people. They’re not otherworldly beings. Depicting them in a way that separates “them” from “us” makes it harder for people in other cities to relate to their stories.

And maybe even worse, it could make the people who live in Chester see themselves in that same, stark, hopeless light, Maxon says.

And so he’s painting the people of Chester in color. Because he wants others to see the full complexity of their lives.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.