‘Am I gonna become obsolete?’ How older workers are being left behind by A.I.

More than a million U.S. workers over 60 years old lost their jobs during the pandemic. Most furloughed workers went back to work, but older adults are getting left behind.

Listen 6:30

A man who has been fired or has resigned from their company walks out carrying boxes. (Big Stock/Charnchai Saeheng)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Susannah Knox worked as a receptionist at law firms in New York City for more than 30 years. As the first point of contact for potential clients, it was her job to transfer calls, schedule appointments, and sort the mailroom. She especially loved to chit-chat with clients and get to know them better.

“I had a lot of people come into the office and the first thing they would do, they would hear my accent, and they’d want to talk about where I was from,” Knox said. “It’s personal.”

Knox immigrated from England to New York when she was 18 years old and she’s worked in customer service since then. First at a big department store, then a caviar purveyor, and most recently at a corporate law firm where she spent more than 20 years building relationships with clients.

“I was there for 21 years,” she said. “I figured I was gonna retire from that place.”

Then her office closed during the pandemic. Knox started answering calls from her home, but soon after she was furloughed. For nearly a year and a half, she waited anxiously to get called back into work until one day she got the call that her services were no longer needed. The law firm didn’t need a human to answer calls or greet clients anymore. Instead, Knox was replaced with an automated voice message that directs callers to a directory. She was devastated and felt like it was a bad business decision.

“When you call a business, you want to hear somebody’s voice. You want somebody to pick up the phone,” said Knox. Yes, an A.I. thing is very efficient, but they don’t have that warmth. It’s making me think: ‘Am I gonna become obsolete? Are employers really going to go for that?’ You almost feel worthless and useless. For them to just dump me after this, sometimes I find myself crying in the night. I’m like, ‘What did I do? Why did they do this to me?’”

Knox is just one of more than a million American workers above the age of 60 who lost their jobs during the pandemic. Most furloughed workers did eventually get called back into work, but the recall rate wasn’t the same for older adults. Many feel like they were left behind.

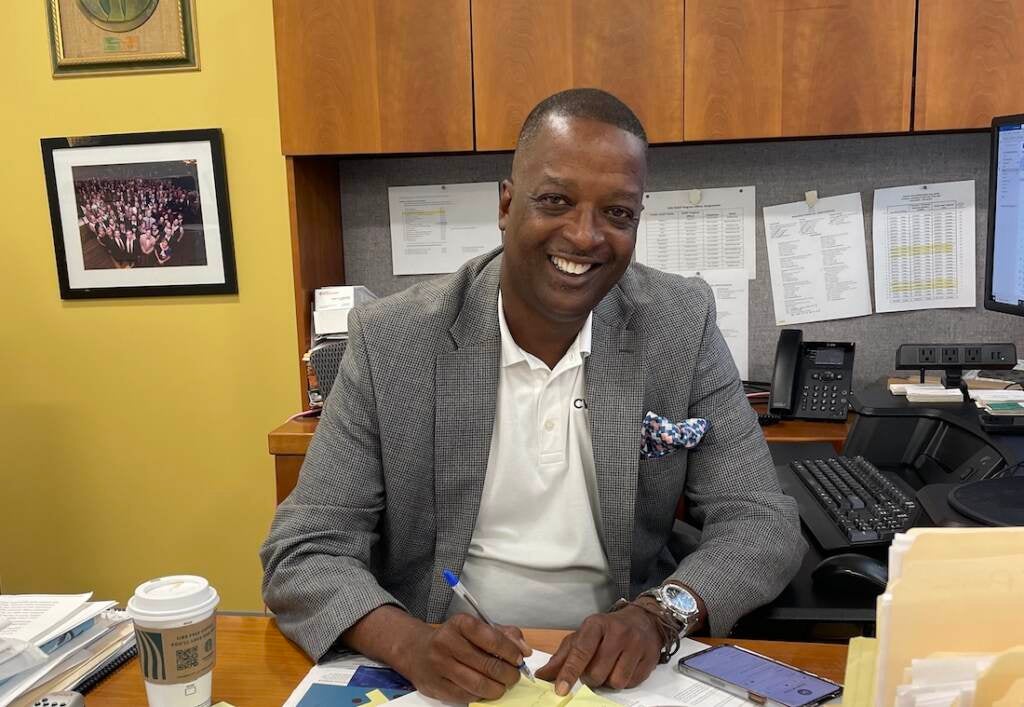

Gary Officer, president and CEO of the Center for Workforce Inclusion, has heard this story time and time again. “I think we have to accept something that many of us do not want to talk about in this country: how culture informs age discrimination.”

Subscribe to The Pulse

During the pandemic, millions of American workers voluntarily resigned from their jobs in a wave some call “The Great Resignation.”

“The Great Resignation did not occur for older Americans,” said Officer. “I referred to it as the great sifting out because many older Americans were not recalled back into their workplace. Many of them were simply let go.”

Officer says there’s a lot of reasons for this. And a major one is related to advances in automation and artificial intelligence. As the technology gets better and better, more traditional skills will become obsolete. New opportunities and jobs will be created, but Officer worries that older workers may not be ready for them.

“By the year 2024, older Americans 50 and over will become the single largest segment of the U.S. workforce,” said Officer. “We cannot ignore the largest segment of the workforce from accessing workforce development dollars that will prepare them for opportunities that our economy will be reliant on going forward.”

But to retrain older workers with digital skills, Officer says we first need to address a more fundamental inequality: internet access. In the U.S., 24 million households still don’t have internet service. More than 4 million say it’s because they can’t afford it.

“If I can’t get on the internet to participate in those online training programs then equity comes into play,” said Officer. “Barriers informed by location come into play. And so, we have to figure out how we can remove those locational barriers that prohibit opportunities. We have an obligation as a society to make sure that everybody has an equal shot at being part of the new mosaic that’s becoming our 21st century workforce.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.