Why ‘stillness’ is crucial for your brain during this pandemic

The idea that you should be optimizing your quarantine time is everywhere. But resisting productivity culture and letting yourself be bored is essential to your well-being.

Listen 13:15

Resisting productivity culture and letting yourself be bored can do a lot for your cognitive health. (Chinnapong/Big Stock Photo)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you get your podcasts.

A lot of messages are being thrown at us during this pandemic. One of them is this idea that we should all be optimizing our time in quarantine, that we should seize the opportunity to be productive.

Social media posts taunt us: “Write that business plan you’ve been meaning to.” “Did you know Shakespeare wrote King Lear during quarantine?” “If you don’t come out of quarantine with a new skill, you didn’t ever lack time… you lacked discipline.”

If you don’t come out of this quarantine with either:

— Jeremy Haynes (@TheJeremyHaynes) April 2, 2020

1.) a new skill

2.) starting what you’ve been putting off like a new business

3.) more knowledge

You didn’t ever lack the time, you lacked the discipline

Ouch.

A round of reactions follow: Stop trying to be productive. It’s enough just to get by. Staying inside and doing nothing right now is plenty.

If this pandemic is a golden opportunity for you to write the next King Lear, congratulations! But lots of us are just trying to get through the day without the added pressure of having to be creatively productive :) https://t.co/Wny6ZOx6ZK

— Michelle Ruiz (@michelleruiz) April 9, 2020

It can feel like a constant push-and-pull. One minute our brains tell us, “relax, it’s fine to do less.” The next, it’s “get off the couch and get to work.”

But a growing body of research suggests that doing nothing, even letting ourselves be occasionally bored, is crucial for our cognitive health. The question is, have we forgotten how?

Pushed to the limit

Lisa Pradhan, 28, is an artist and community organizer living in Oakland, California. Being “productive” and finding meaning through work have always been important to her.

“I really internalized at a young age that I needed to do the most,” she said. “And I think I really set up a series of ways of relating to work and productivity and self-worth where I was really pushing myself to the limit.”

In high school, Pradhan was one of those kids on the AP/honors track, and there was a certain culture to that.

“It’s a career-building channel,” she said. “And I think by being part of that, I really surrounded myself with kids who were pushing themselves really, really, really, really hard.”

In her junior year, the stress caught up with her. She had to take time off school. “Because I just started getting super sick and no one knew why. I just started having all this pain,” she said. “At the time, it felt like my body was falling apart.”

But Pradhan came back, and pushed herself even harder in college, taking seven or eight classes a semester, while working multiple jobs and volunteering, yet “still feeling this feeling of, ‘I’m not doing enough,’” she said.

After college, Pradhan worked a full-time job by day. By night, she worked on her own art and joined efforts to build up arts spaces for Asian Pacific Islanders and queer folks of color in the Bay Area. She’d go to community meetings, apply for grants, or work on a project for a show until late. Sometimes, she’d forget to eat.

Not only was this “always-on” lifestyle taking a toll on Pradhan’s body, it was also emotionally and psychologically draining. “When you’re stressed out all the time, it’s really hard to show up in the world the way you want to,” she said.

But Pradhan didn’t know how to stop, or what to change. Then, in 2017, two major incidents happened back-to-back. A stranger assaulted Pradhan and a friend while yelling slurs at them. Pradhan asked to take some time off from work, and a few days later was laid off from her job. She doesn’t think her request for time off was related to the layoff, but the timing stung. It was a breaking point.

“I sorta just reached this point where I was, like, these systems that are in place aren’t necessarily going to look out for me or my well-being. And so I have to do that,” she said. “Like, you know what? I’ve been doing all these different things in my life, and it hasn’t brought me happiness. It hasn’t brought me joy. It has just made me feel really tired all the time.”

Pradhan made the decision to take the next year off, live off unemployment and savings, and learn how to be still.

“I just gave myself permission to not do anything for a while,” she said. “To just focus on having energy, and focus on mending myself.”

Doing nothing deliciously

A lot of us go, go, go, go until we can’t. Experts say this impulse to always be doing something may be especially strong for younger generations — starting with millennials, who grew up in a hypercompetitive culture of scheduled extracurriculars and college prep, not to mention lots of screen time. Every moment of the day had to be filled with activity.

Now, as working adults, the effects of hustle culture are starting to catch up to many of them. Some have given these effects a name: “millennial burnout.”

“This has, for years, long been a hobby horse of mine,” said Tim Herrera, editor of Smarter Living, a section in The New York Times that gives tips for how to live a better and more fulfilling life. Herrera is a big proponent of doing nothing.

“I feel, like so many other millennials, just kind of, it’s been ingrained in us that we need to subscribe to hustle culture, and always need to be maximizing productivity, and always be monetizing our hobbies, and everything should be for the purpose of career advancement,” he said.

“I think it’s poisonous and really destructive to our own happiness and our sense of identity,” he said. “And on a more practical level, it’s destructive to our overall productivity.”

Smarter Living has published a lot on this topic over the years. According to Herrera, there’s always some backlash to these articles.

“You know, it seems like a very American idea to look down on people who take breaks,” he said. “Culturally, we are trained to see idle time as almost a character flaw.”

But Herrera is steadfast in his belief that we need more idle time in our lives.

“The research and scientific evidence is perfectly clear, very unambiguous,” he said. “We know this is how to be more productive. And you can read any book on productivity, talk to any experts. Taking time for idleness and to daydream, these are tips that everybody who knows what they’re talking about sings the praises of, because we know that they work.”

One of those experts is a psychologist named Doreen Dodgen-Magee. She thinks our obsession with productivity has made us averse to boredom. Researchers have even found that people would rather be electrically shocked than sit alone with their thoughts.

Now, with everyone carrying mini-computers in their pockets, people have more ways to fill up every moment of stillness, Dodgen-Magee said. She worries many of us can’t even wait in line a few minutes without pulling out our phones to respond to emails, or level up on a game.

That’s a problem, because it seems our brains actually need to be bored every now and then.

“The prefrontal cortex, which is the part of the brain that is responsible for things like attuned communication and starting and stopping behaviors, self-reflection and self-knowing awareness, is a part of the brain that really is stimulated to create robust wiring in the absence of other stimulation,” Dodgen-Magee said.

Meaning the brain requires some level of boredom for neurons in the prefrontal cortex to fire and create new connections.

The prefrontal cortex plays an important role in emotional regulation. It helps us have what Dodgen-Magee calls an internal locus of control: “the ability to soothe ourselves and come back to center, rather than always needing to be stimulated or held by things outside of us,” she said.

It makes sense: Being bored lets us learn how to be content without distraction. Once you know what that feels like, it’s easier to return to it. The calm within yourself becomes like a muscle you can use when things aren’t going as well.

“So it just helps us develop these really beautifully important psychological traits of grit and resilience like nothing else does,” Dodgen-Magee said. On the flip side, when we’re cognitively taxed all the time, we have trouble regulating our emotions. We’re faster to anger, and less able to weather frustration.

Researchers have also found that the ability to tolerate boredom is correlated with creativity.

“There is the idea that when we allow ourselves to be idle, it increases the likelihood that we will become uncomfortable enough that we will get creative with our surroundings, or even just creative within ourselves, to find ways of having meaningful experiences,” Dodgen-Magee said.

When she talks about idleness, she doesn’t mean taking a break from work to scroll Instagram, she said. She means resist filling the moment. Let your mind drift aimlessly.

“Just sitting and looking out of a window, or sitting on one’s porch and watching as the day goes by,” she said. “The Dutch call this niksen, which means ‘doing nothing deliciously.’”

The myth of productivity?

But niksen feels unproductive, right? It might even make you feel anxious, or guilty. Why is that? Or, conversely, why do we care so deeply about being busy and productive — all the time?

Silvia Bellezza has a hypothesis. She’s a professor of marketing at Columbia University’s business school, and she studies status symbols. She became interested in our obsession with being busy because of a contradiction she noticed.

In her field, the classic idea is that leisure time is a status symbol. An American economist named Thorstein Veblen wrote about that in the late 1800s.

“He talks about the idea that the extremely wealthy people are the ones who can afford not to work,” Bellezza said. “So he specifically says that ‘conspicuous abstention from labor’ becomes a manifestation of the fact that you’re particularly wealthy.”

But all around her, Bellezza saw pretty much the opposite.

“People are bragging all the time about working nonstop, not going on leisure, even when you’re supposed to be on holiday, bragging about the fact that you’re working,” she said.

Bellezza thought: Today, being busy is the status symbol. She tested this out, a bunch of different ways, to see if it was really true.

For example, she created fake Facebook profiles. One profile would be filled with posts about working nonstop, being super busy. The other would have posts about having tons of free time. Then she asked study participants to rate the profiles: Do you think this person is wealthy? How would you rank their social status?

“What we find recurrently is that there is this significant difference,” Bellezza said, “such that the person who’s working all the time is seen as higher status than the person who’s engaging in leisure.”

But that was only true for participants in the United States. When Bellezza did a similar experiment with Italians, she found the opposite.

“For the Italians, as soon as they see the person who’s not working, they immediately think the person is well-off. That’s why they’re not working,” she said.

Bellezza then looked into why participants in different countries felt the way they did. And it came down to perceived social mobility — aka the American Dream.

“In countries like the U.S., in which people really think that through hard work, you can make it to the top of society, we find that in those countries being busy at work and being a workaholic is typically seen very positively,” she said.

So what has changed in the United States since when leisure was seen as the mark of wealth? According to Bellezza, it’s the shift toward a knowledge-intensive economy, one in which workers are encouraged to constantly build and invest in their own capital, by going to the best schools, paying for specialized degrees, and overworking.

“The idea is that there is a market for human capital,” she said. “The extent to which we are busy at work, this implies that we’re very in demand. And scarce. If you see a person that’s driving an expensive car, you may think of them as particularly wealthy because what they own is scarce. When you’re bragging about being busy and overworked, the scarce resource is really your brain.”

Malcolm Harris is a Philadelphia-based journalist and author of a book called “Kids These Days: Human Capital and the Making of Millennials.” In the book, he argues that this restructuring of labor is precisely what constitutes the millennial experience.

“Millennials know that we need to make ourselves useful for employers. It’s not a question of just going and picking up a job. It’s ‘how do you become career ready?’ And we internalize these injunctions,” he said.

For instance, Harris said, instead of paying to train you, companies today expect employees to train themselves.

“The result has been we have the most educated cohort in American history, right? However, that hasn’t led to the good jobs that were promised,” he said.

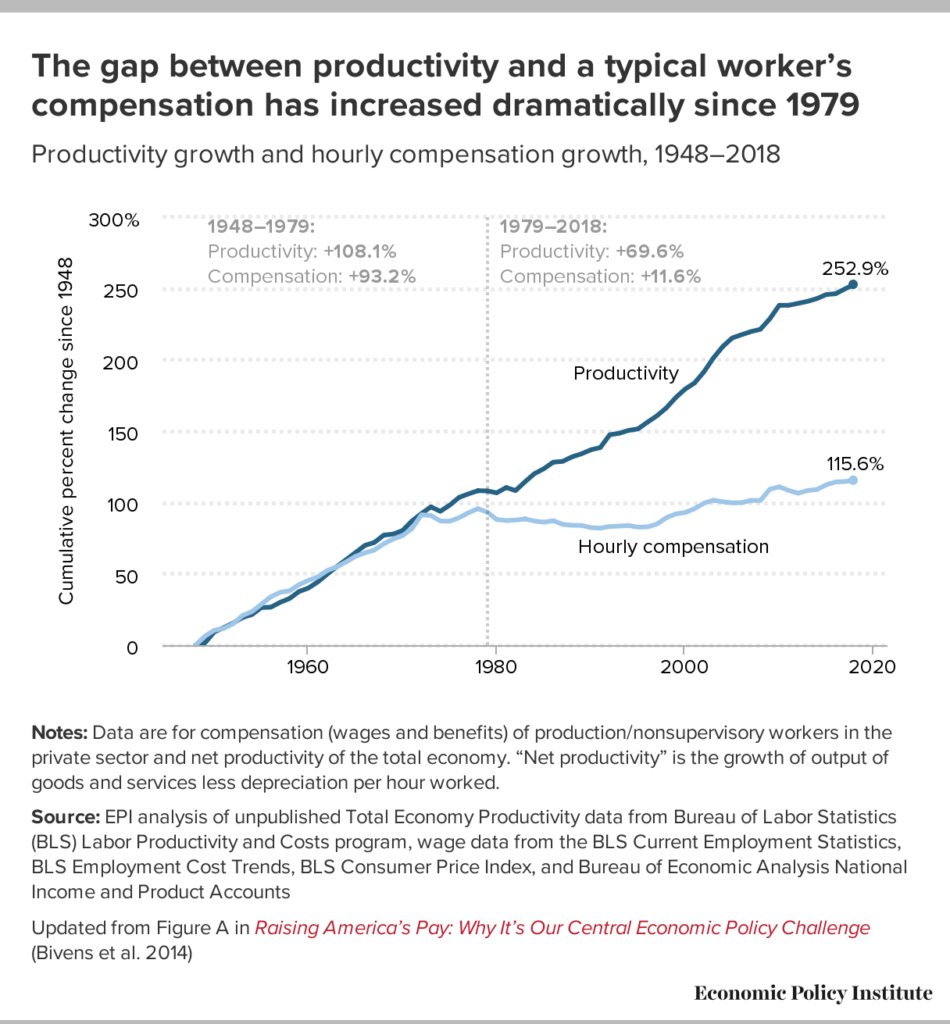

To explain why, Harris pointed to something called the productivity-pay gap. Around the 1980s, when millennials start being born, you begin to see a widening gulf between labor and compensation.

“People stopped getting paid more for their work,” Harris said, “and at the same time they continue to become more productive. And this divergence grows and grows and grows and grows. And it’s kept growing over the past few decades.”

All this feeds into hustle culture, according to Harris. Workers have to compete more for wages, so they push themselves harder. They take on more educational debt, which requires them to work more.

“It builds on itself. And it keeps building,” he said.

All the while, the American Dream, the thing that causes us to scorn laziness and prize industriousness — “sometimes that’s true, and mostly we know it’s not very true,” Harris said.

Today, many economists and sociologists say, the circumstances into which you are born are more decisive of life outcomes than how hard you work. That’s why Harris thinks, ultimately, the solution to productivity culture is not an individual one.

“It’s only by thinking about these questions collectively that we can start to come up with answers that might be appropriate to the question itself. Which is, how do we solve this as a social question, not how do I solve this as a person?” he said.

Doreen Dodgen-Magee, the psychologist, agreed with Harris.

“The grind-and-hustle mindset is really fed by a capitalistic culture that is based on the thriving of certain parts of our populace and the oppression of others,” she said. “And the folks who are doing the majority of the grinding and hustling are given less and less opportunities for things like rest, for things like prioritizing self-care.”

But Dodgen-Magee also thinks it’s worth it for people to work in little moments of mental rest whenever they can. She believes it all helps.

“We tend to think about things in a very strong all-or-nothing way,” she said. “And that’s where I’m trying to break in to say it can be a little more gray. If we have very, very stressful work environments, then learning the practice of taking even three minutes to do some things like breathing and to let my mind kind of wander, even those tiny moments can go a long way toward soothing the self.”

Dodgen-Magee recognizes there’s an irony to the “work less, you’ll get more done” argument. She worries it reinforces the very productivity mindset she’s trying to fight. For instance, she said, think of the trends toward quantifying leisure: Now, the simple act of going on a walk can become all about tracking your step count.

Jordan Etkin, a professor of marketing at Duke University’s Fuqua School of Business, calls this “productive leisure.” And there are consequences to leisure getting hijacked by productivity, she said.

In her research, she’s found that even simple acts of monitoring — like, asking people to check off shapes that they’ve filled in in a coloring book — can counteract the replenishing effects they would have gotten from coloring aimlessly.

If we’re coloring with no other task at hand, we free our minds from having to focus, according to Etkin.

“Maybe we’re thinking about what color to use. Maybe we’re thinking about the shapes. Maybe we’re just sort of thinking about our day and ruminating on some upcoming plans,” she said. The point is, “that’s very restorative for our brains.”

That’s why Dodgen-Magee said unwinding has to be its own reward. Do nothing for the sake of doing nothing.

‘You’re doing enough’

As Lisa Pradhan in Oakland forced herself to take a break, after having been laid off, she felt herself slowly adjusting.

“I did feel a deep sense of clarity in my life,” she said. “I think there’s a lot of things that we can fixate on in this world. When I really sat with it — and had time to think through, ‘Why am I choosing to do X thing?’ — and to actually have the space to hold that, and to not feel too overwhelmed to take on those questions, I found that I did make different choices about what matters and what doesn’t matter.”

Some days, what mattered was honoring her need to unplug or be lazy. “OK, I’m not gonna have my phone on for today,” she said. “And I’m just going to do whatever I feel like doing, and if what I feel like doing is just hanging out in my bed all day, then that’s what I need right now.”

Other days, it was creating art, without needing the end result to be perfect. “And I ended up being incredibly productive when that wasn’t my goal per se,” she said.

Eventually, Pradhan got a new full-time job, working for an environmental justice nonprofit. She’s gotten better at noticing when she’s overextended — like when she has back or stomach pain, or if she can’t fathom reading a book at night — and she’s careful not to take on too much, at work and in the rest of life.

“I kind of pause every now and then, and I’m just like, ‘You’re doing enough, Lisa. You’re doing more than enough. You’re doing great,’” Pradhan said. “I really remind myself that I am enough. As I am in this world, that is enough.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.

![CoronavirusPandemic_1024x512[1]](https://whyy.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/CoronavirusPandemic_1024x5121-300x150.jpg)