Using a balloon, a fishnet and a camera to calculate crowds

Listen

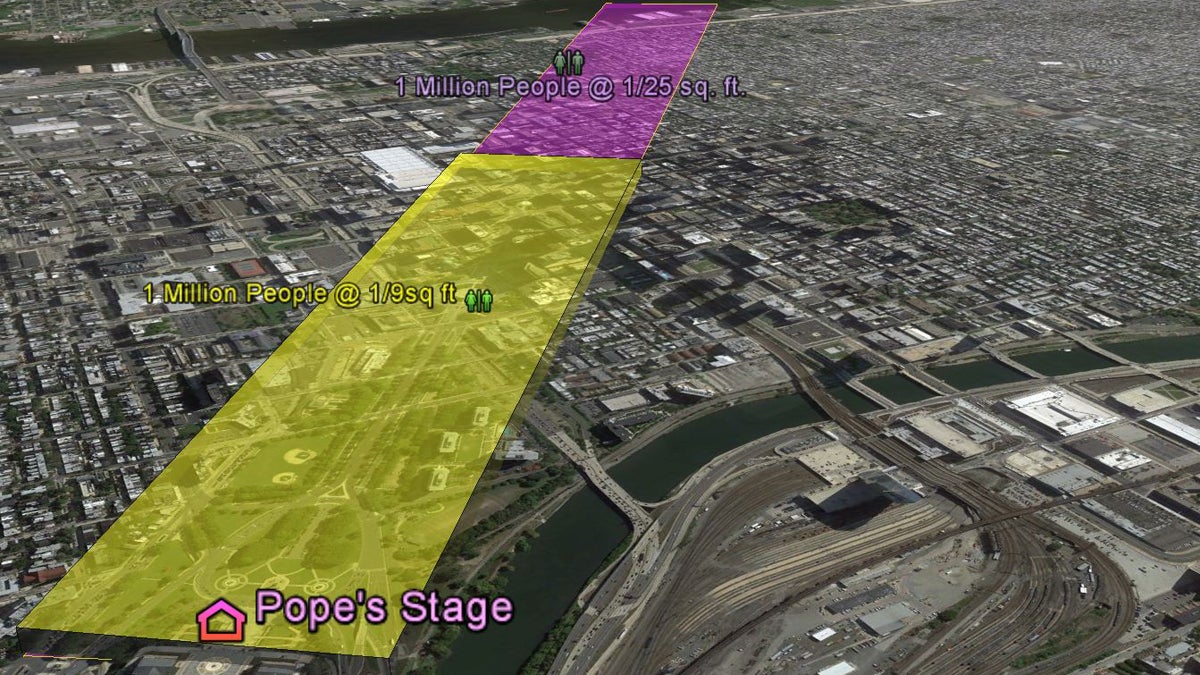

(Visualization Image by www.AirPhotosLIVE.com)

Will they come? Or rather, how many? The number of papal pilgrims who come to see the pontiff in Philadelphia next weekend is one of the biggest remaining unknowns about a visit that has been years in the making.

First, pilgrims were warned by city officials of long walks and lines to see the Pope. Then, amid fears that these warnings were scaring visitors away, they were told it wouldn’t be so bad.

Crowd-counting techniques have long left room for debate after large events are over, and though technological advancements have driven the field forward, it looks like the papal mass on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway is likely to be surveyed in a more old-fashioned way.

Estimating crowds can be a controversial business

Estimating how many people attend a political rally, demonstration or other large-scale event has long been tricky. The organizers or promoters of events who usually make estimates often have a stake in how large or small that number is, as turn-out is often used as a proxy for support for a political candidate or cause.

Perhaps the best-known crowd-counting controversy was the Million Man March, organized in Washington, D.C. by the Nation of Islam in 1995.

The National Park Service estimated 400,000 marchers were on and around the national mall for the event. The Nation of Islam thought it was between one and a half and two million, and threatened to sue over what it’s leader Louis Farrakhan saw as a low-ball count fueled by racism.

Boston University researchers eventually placed the crowd at 837,000, with a 20 percent margin of error, and the National Park Service eventually stopped making official estimates.

Using a grid

The importance and extreme subjectivity of crowd counting was something Herbert Jacobs, the grandfather of modern crowd-counting, understood well.

Jacobs was a newspaper reporter from Wisconsin who went on to teach journalism at the University of California Berkeley in the 1960s.

“He got interested in the estimation of crowds, because at the time there were demonstrations nearly every day, [against the Vietnam War, for civil rights, for free speech],” said Robert Sanders, a writer in the news office at the University of California, Berkley.

The newspapers were publishing crowd estimates that Jacobs thought might be over-inflated, so he looked for a technique to improve these estimates. He noticed that the site of these demonstrations, Berkeley’s Sproul Plaza, was neatly divided by lines in the stone paving.

“It had a grid pattern, and he thought, ‘Well if I could get an estimate of how many people [fit] in one of these squares, and multiply by the number of squares, I might be able to get a good estimate of the crowd size,'” Sanders said.

Jacobs got the exact dimensions of the squares in the plaza grid from blueprints, then counted how many people fit into each square to develop an average square foot figure per person.

“He would calculate the size of the space they were gathered in, divide by the square foot per person, and come up with a good crowd estimate,” Sanders said.

The fundamental idea behind crowd-counting has remained unchanged ever since. But as technology has gotten better, with aerial photography, 3D computer modeling and remote sensing technology, a desire for more precise measurements has grown.

The new science of crowd counting

Curt Westergard is one of those on the quest for precision. His Falls Church, Virginia, company Digital Design and Imaging Service (DDIS), which specializes in aerial photography and surveying, got into the game of crowd counting in a rather unexpected way.

“Somebody called us from Ireland, and was trying to set a world record of clog dancing in Galway,” Westergard said.

Westergard’s company didn’t end up counting those cloggers, but the request did spark his interest in the science of crowd sizes.

DDIS went on to estimate attendance at high-profile events including dueling 2010 Glenn Beck and Stephen Colbert rallies for CBS News. He now uses a combination of 3D modeling and 360-degree aerial photography to estimate large crowds, mostly on the National Mall.

DDIS starts any new job by surveying the event location to make a computer model of the area. Westergard describes his method not as laying a grid over a flat surface, like the traditional method, but digitally laying a fishnet on top of a 3D model to capture topography.

“We try to drape the fishnet over the landscape,” Westergard said.

For events on the National Mall in Washington, D.C., for example, Westergard takes into account a hill that the Washington Monument stands on.

“One square (there) might actually be embracing a downhill part where there’s going to be more people,” Westergard said.

Westergard’s team also scouts areas where people tend to pack together. Popular spots are behind windbreaks in the winter or under the shade in the summer, near stages and TV screens, and on low walls or embankments that offer natural seating. People tend to avoid areas where their view would be obstructed.

During Pope Francis’s upcoming mass on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway in Philadelphia, Westergard expects people to cluster near TV screens and on a set of baseball diamonds near the parkway that provide wide open space and a view.

Once this kind of ground reconnaissance is done, Westergard and his team take a series of high-resolution photos from a three-camera array lofted on an tethered aerostat balloon. The balloon is launched from a mobile trailer that serves as HQ and mission control during events.

Unlike those who estimate crowds from TV footage of still images shot from helicopters, Westergard and his lead photographer Ryan Shuler can capture and count people gathered under trees or other cover by taking pictures with their balloon at low elevations, 10 and 20 feet below ground.

Then, they lift the balloon higher, taking 360-degree photos at intervals hundreds of feet above the crowd.

When shooting is done, Shuler pinpoints the image that captured the crowd at its highest density and overlays the fishnet grid. Then, he calculates how many squares are packed to different densities: from what he calls “mob density” at three to four square feet per person, “roughly front to back and shoulder to shoulder,” to medium density, about one person per nine square feet, and low density, one person per 25 square feet.

Shuler then counts the number of squares in the photo with each of those densities and uses that to estimate attendance, refining the basic grid estimating technique Herbert Jacobs devised in the 1960s.

No Stephen Colbert treatment for the Pope

There is one major downside to using this newer, snazzier technology: flights above large events have to be approved, and for the Pope’s visit, security has been extraordinarily tight.

“The FAA [Federal Aviation Administration] has very clearly said absolutely nothing will be in the air,” Westergard said.

So instead of estimating the crowd on the day of the event, Westergard will be watching it on TV like the rest of us. He did make a graphic ahead of the event, showing how far a million spectators would stretch down the Benjamin Franklin Parkway.

“Our main goal on that is to really just say, what would a million people in Philadelphia look like?” Westergard said, “and in that way you stop the speculation that you had with the Million Man March.”

At one person per nine square feet, Westergard said a million spectators would cover a swath of downtown Philadelphia four football fields wide and nineteen football fields long, from the Philadelphia Art Museum to about City Hall.

ESM Productions, which will be running sound and TV feeds of the papal mass, expect “north of 300,000” people will fit on the Parkway between the Philadelphia Art Museum and City Hall. They say anyone in that area will be able to hear the mass and see it live or on a Jumbotron.

Unlike the Million Man March back in 1995, the papal mass will have a large ticketed area and a viewing area behind a security checkpoint, which should make estimating the crowd size somewhat easier.

ESM said they will have an exact count of how many people entered the ticketed area closest to the stage, from the Art Museum to 20th Street.

A spokeswoman for the City of Philadelphia said spectators who enter the fenced perimeter surrounding the parkway will be counted for crowd-control purposes, and the City will release an official crowd estimate after the event.

It’s not clear if, or how, those outside the security perimeter will be included in that estimate.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.