To understand the Vietnam War, you’d have had to live through it

The Vietnam War impacted much more than its name implies. For people like my parents, we don’t talk about it. Like the American public, we’ve just accepted what’s been said.

Listen 4:50

(Wikimedia Commons)

This story is part of a WHYY series examining how the United States, four decades later, is still processing the Vietnam War. To learn more about the topic, watch Ken Burns and Lynn Novicks’ 10-part documentary “The Vietnam War.” WHYY members will have extended on-demand access to the series via WHYY Passport through the end of 2017.

—

There have been mixed emotions for me watching Ken Burns’ “The Vietnam War.” There are parts where I sit with my arms folded, muttering to myself how much I already know, wondering why we are 40 years late in executing this.

The series is 10 episodes long, I imagine, to cover the vast perspectives of the many, many people involved, and in part because of how little the American audience knows — a theme repeated throughout.

I learned a lot, too, and I appreciate that much of it comes from interviews with not only Americans but also the Vietnamese — former soldiers of both the North and South armies, the Viet Minh, province chiefs, sons and daughters of government officials. Some names don’t even have a corresponding title, just where they’re from. These are regular people, and they are retelling their own history. It’s a rather welcome change from the dry matter-of-fact talking points of scholars, because studying wars and living through them are completely different narratives. Throughout it, I anticipate and wait for moments that mention Laos, the neighboring country where my parents are from, but also find it painful to watch these stories of people who look like them too.

The Vietnam War impacted so much more than its title implies. To put it into perspective, we Americans call it the Vietnam War, however, in Vietnam, it’s the “American War.” For people like my parents, who are refugees, also fighting their own civil war, also suffering from a history of French colonialism, Japanese occupation, and U.S. flip-flopping diplomacy — it’s not called anything. We don’t talk about it. Even now. Just like the American public, we’ve just accepted what’s been said.

During the early years of my childhood I had always believed my parents emigrated, dreaming of a new life, choosing the United States as their new home. Little did I know about the “choices” refugees get to make. Having to choose between living under a Communist regime or a royalist ruler. Having to leave the only home they’d ever known or remain to face two other dangerous options: suspecting soldiers or the unexploded bombs scattered by American planes. Having me, their first-born child, in a refugee camp in a country not of their origin, or one with an uncertain future. Having to go elsewhere not knowing what freedoms would exist for them or accept being citizens of the very country that made them refugees in the first place. Having to listen to a history that’s excluded them entirely or risk being called ungrateful for daring to challenge the government that took them in.

It’s been over for 40 years. What do we get to talk about then?

To quote one of the commentators in the documentary, Bao Ninh, a veteran of the North Vietnamese Army, “It’s been 40 years. Even the Vietnamese veterans, we avoid talking about the war. People sing about victory, about liberation. They’re wrong. Who won and who lost is not a question. In war, no one wins or loses. There is only destruction. Only those who have never fought like to argue about who won and who lost.”

With that I’d add that to really understand a war you’d have to have lived through it all — or perhaps I should I say, survived it. The events that escalate up to a full-blown war always include human casualties. It’s an essential part. If you can say you witnessed peace turn into fighting and chaos, and managed to stay alive until the very end, then you are certainly the most qualified to speak on it. But I doubt that anyone who has seen that much wants to relive it.

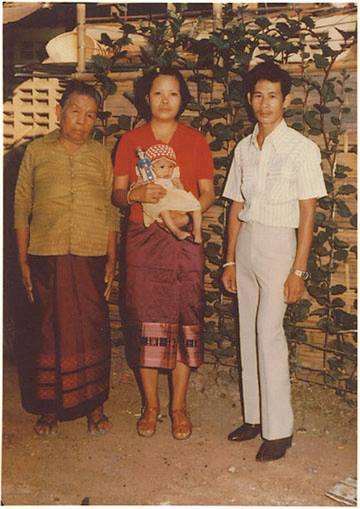

That’s not to say you weren’t impacted by the war if you weren’t inside of it. I was born after the wars ended in 1975, but because my mom gave birth in a refugee camp, the process of gaining my American identity is rooted in my green card status. While my entire upbringing has been American, I have never see pictures of my parents’ youth — just a couple black-and-white photos of them holding chalkboards stating their family name, camp location, and year. Their silence about their life before the United States only ignites my curiosity about how we got here and why the history lessons about Vietnam did not include the surrounding Laos or Cambodia.

There are soldiers who fought for the side of America yet are not officially recognized as veterans, and subsequently will not get veterans’ benefits. Watching these men get caught in such an impossible scenario, I often find myself rooting for all refugees, regardless of where they come from, because I know America has played a part in it.

It also leaves me conflicted as I look at the racist neighbors we had growing up in South Philly. What had we fought for? And I try to empathize. Maybe they had a brother, father, husband, or uncle who served in Vietnam who died or returned home missing parts of their body, or came back a different person. While the end of Vietnam War media coverage talked about loss, regret, and failed diplomacy, those families perhaps were trying to salvage some kind of brave memory for their fallen soldier, and the only way they knew how was by resenting my existence, hating that I got to live with my freedom in their America.

I know people grieve in different ways, but that psychological projection is the form I hate the most — driving the false narrative that I, my family, and the approximately 130,000 Southeast Asians resettled as refugees in the U.S., we were all saved by American soldiers. We know that’s not true. The unsuspecting villagers, many of them children, whose lives and limbs are still claimed by the unexploded bombs that contaminate 30 percent of Laos, know that’s not true. The American soldiers who flew those planes from 1964 to 1973, in over 580,000 bombing missions, know that’s not true.

The Rambo-esque movies that depict jungle Asians as savages, and American white men as saviors, are fiction. I’m not saying that there weren’t any soldiers who went into it believing they were righteously fighting for the freedoms of others, but the United States was doing a little more than helping out. And yes, popular movies show the breakdown of the American psyche, but again, these films center mainly around U.S. soldiers. I wonder what movies or tv shows the other American kids I grew up with remember about the war, if they were even allowed to watch them.

I remember a film shown in school, “The Girl Who Spelled Freedom,” based on the real-life story of a Khmer refugee family sponsored in Tennessee whose daughter goes to win the spelling bee. I had always felt a kinship with that film, mostly because I had become that girl in my own school to ace spelling quizzes and grammar tests, my grades practically beating out all my classmates in the subject of English, despite having constantly been asked outside of school if I spoke the language. I also wonder, with all that’s available to us now in the Internet Age: Has the average American seen “Nerakhoon: The Betrayal,” or “Don’t Think I’ve Forgotten”?

If not for Hollywood spin, will our stories ever get attention? Angelina Jolie’s got a 15-year marketing campaign, which all started when she adopted her first son, Maddox, from a Cambodian orphanage. Few of us are lucky to have our stories get that kind of advertisement. After 40 years, does America still care? For those of us watching this documentary now simultaneously, why are we doing it? Perhaps to get acknowledgement, a little shout out in such a long saga of American history.

It is this psychology my parents have gotten used to. Let them say what they want. What matters is that you are alive. But for me, being alive is what allows for us to make sure that the stories that get told about us are told by us. And when it comes to war, despite how many are fighting or affected, it really only has two sides: before and after.

—

Catzie Vilayphonh is an award-winning spoken-word poet, writer and performance artist. She is the creative director of Laos in the House, a project that promotes storytelling in the Lao-American refugee community, and is a founding member of the group Yellow Rage who were featured on HBO’s Def Poetry Jam. Through her work, Catzie provides an awareness not often heard, drawing from personal narrative. She has worked on various artistic projects with partners such as Mural Arts Philadelphia, Asian Arts Initiative, Smithsonian APIA Center, The Moth, Philadelphia Assembled and Legacies of War.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.