Transparency about fracking chemicals remains elusive

Listen

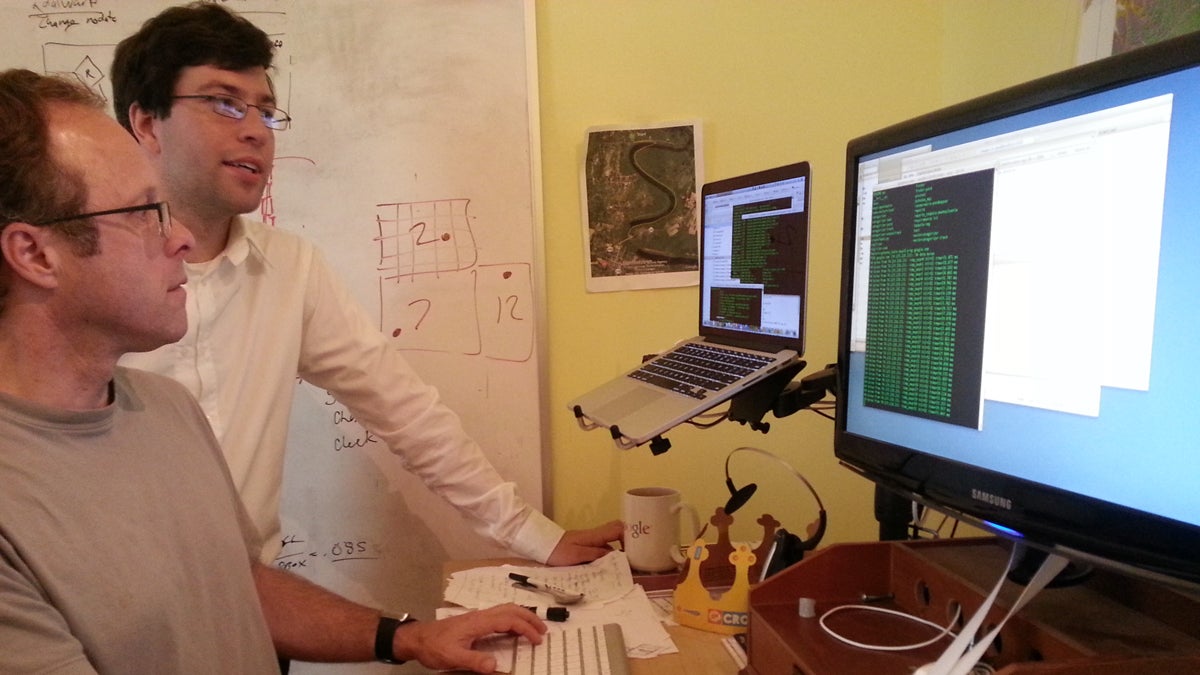

Paul Woods

Some groups are taking issue with how one website, aimed at providing public disclosure on fracking chemicals, is making that data available.

The website FracFocus.org was built to give the public answers to a burning question about the shale boom: what exactly were companies pumping down tens of thousands of wells to release oil and gas?

Today, FracFocus has records for more than 77,000 wells. Pennsylvania is one of 14 states requiring operators to use the website as part of their chemical disclosure laws, according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

However, transparency about those chemicals remains elusive.

“We were just trying to do some good”

FracFocus is run by the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission and the Groundwater Protection Council, both based in Oklahoma City. The IOGCC is a multi-state government agency and the GWPC is a nonprofit group of state regulators who oversee water quality and oil and gas development. Pennsylvania is a member of both organizations.

“We were just trying to do some good,” says GWPC Associate Director Dan Yates, “Get some data out there on something we felt the public was hungry for.”

With funding from industry trade groups, FracFocus launched in April 2011 as an optional disclosure tool. More than 200 operators voluntarily uploaded their fracking fluid recipes for each well – with the exception of those ingredients companies deemed “trade secrets.”

One year later, the voluntary disclosure site started to become a required regulatory tool in several states, including Pennsylvania.

Yates says the goal was to provide a well-by-well service.

“We really wanted to focus in on individual people who lived and worked near a well, what they needed to know about that well,” he says.

That’s a problem, according to David Manthos with the group SkyTruth.

He says information about tens of thousands of wells is technically available to the public on FracFocus, “but in such an obscure, obtuse way that it’s impossible to look at it in aggregate.”

Big data on drilling locked away

SkyTruth is a nonprofit that uses publicly available data and satellite images to monitor the impacts of industry on the environment – all from a tiny office in Shepherdstown, West Virginia.

When the SkyTruth team learned about FracFocus, Manthos says they were excited to find a new data set on shale development. The reports included information about the volume of water, sand and chemicals companies used to frack, as well as the location, height and depth of each well.

However, the data wasn’t so easy to get.

Drillers post their lists of chemicals as individual PDF documents for each well they frack. PDFs are not “machine-readable.” In other words, computers can’t understand the documents, so it’s harder to tell machines to pull the data out and organize the information as a table or a spreadsheet. (An Excel spreadsheet is one example of a “machine-readable” document.)

Click here to see what a FracFocus report looks like.

At the time, FracFocus had records for more than 30,000 wells.

To mine all that data, SkyTruth would have to open one PDF at a time and then copy and paste all the information about each ingredient into a spreadsheet.

Manthos says it was a daunting task.

“We calculated about 6 years’ worth of labor and just at minimum wage, would have been something on the order of $90,000 just to manually do this whole thing,” he says.

Paul Woods, SkyTruth’s self-described “big data wrangler,” spent about three months coming up with a better solution. He designed a bot – a software program that could do all the work for them.

Every night, the bot scraped the site for all the available PDF documents and compiled the information into a searchable database. SkyTruth published that database online for the public in 2012.

“We were overwhelmed by the response of people contacting us, asking questions about the data set, downloading it and then the subsequent reports and publications that used that data set to say very interesting things,” Woods says.

For instance, researchers at the Argonne National Laboratory near Chicago used the data to look at how much water goes into producing natural gas and using it as a transportation fuel.

The Smithsonian used it to make an interactive map of shale gas wells across the country. Even a consulting firm that does data analysis for the industry tapped into SkyTruth’s database.

But one night last June, the bot hit a roadblock.

The first thing Woods noticed was that there was no new data coming in from FracFocus. He ran some tests and was discouraged by what he found.

“There was a little error message that was coming out saying, ‘Hey, you’re sending too many requests. You’re being blocked for 24 hours,'” he says. “Then, they block you for 48 hours and then they block you forever.”

The GWPC had set up a system to block automated programs like SkyTruth’s bot. Yates says it was “out of concern about overloading our system resources.”

FracFocus under new scrutiny

The new blocking program was part of an overhaul of FracFocus launched on June 1, 2013. “FracFocus 2.0” included new search tools and more flexibility on the back end of the site so companies could tailor their reports to meet different states’ disclosure requirements.

“We didn’t want automated searches overloading the system and blocking or slowing down individual public access,” Yates says, noting that the site was meant for residents and landowners, not groups like SkyTruth looking for big data on drilling.

To get companies to voluntarily disclose what’s in their fracking fluid, the GWPC and IOGCC had to agree it would only serve up the information one well at a time. The industry didn’t want FracFocus to be a wholesale repository of data.

“That agreement is still in place,” Yates says. “We think that’s more than likely going to change, but we’re not actively seeking that out.”

FracFocus has come under new scrutiny as the U.S. Bureau of Land Management considers whether to use it as a disclosure tool for fracking on federal and Indian lands.

The BLM recently finished combing through more than one million public comments on the draft rule. Spokeswoman Bev Winston says the agency is in the process of writing the final regulation and it is not clear whether the website will play a role.

“Like it or not, FracFocus is now one of the most comprehensive, if not the most comprehensive source of information about the chemicals being used in unconventional oil and gas development,” says Kate Konschnik, director of the Environmental Policy Initiative at Harvard Law School.

In a 2013 report, Konschnik gave FracFocus a failing grade as a disclosure tool. She found that the data were often inaccurate or incomplete, and that companies were making “trade secret” claims for chemicals at one well site while fully disclosing the same chemicals at another.

“Not maybe as robust a tool as one would hope if something is regulated or required by state law,” she says.

In March, a task force convened by the U.S. Secretary of Energy’s Advisory Board recommended that the site’s administrators beef up quality control and allow the public better access to the data in aggregate or wholesale form. The task force also recommended federal funding for these improvements.

Morgan Wagner, a spokeswoman for Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection says the agency “is in support of the Advisory Board’s recommendations.”

Konschnik says the groups running the site are under more pressure to make changes, but are juggling multiple interests – the industry, the states and now, the federal government.

Yates admits FracFocus could be improved and says the administrators are already working to fix some of the site’s limitations, but it will be up to the industry and the states to decide whether to release the full data set to the public.

“We certainly have capability to make that happen,” he says. “The technical know-how exists.”

“If we didn’t build it, there wouldn’t be a FracFocus. Though it has some limitations, it’s better than not existing at all.”

“They haven’t really accomplished public disclosure”

What became of SkyTruth’s efforts to get the data?

It’s been just over a year since the bot was blocked from the site. Woods says the group is stalled.

In the spring, SkyTruth teamed up with another environmental nonprofit called FracTracker, based in Pittsburgh, to try to work things out with the site’s administrators. So far, they have not reached an agreement.

Yates says the blocking system is no longer needed and will eventually be removed. However, he could not say when that will happen.

FracFocus is still a unique source of information about a technology that is changing communities and the global energy economy.

But data miners are frustrated that the big information inside FracFocus has been purposefully made so small.

Samantha Malone with FracTracker puts it this way:

“Imagine trying to understand your financial spending throughout the year by taking photos of all of your receipts of anything you ever purchased the entire year,” she says. “You would need to look at each one, one at a time and even then you still couldn’t see the big picture.”

Without big data, Woods says, even individual homeowners can’t see the big picture of how the shale boom is impacting them or their communities.

“The kind of people who can answer those questions for you are people like us,” he says. “And if we can’t get the data because they only want to give it to individual homeowners about their individual wells, then they haven’t really accomplished public disclosure.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.