This week in science history, dialing across the Atlantic

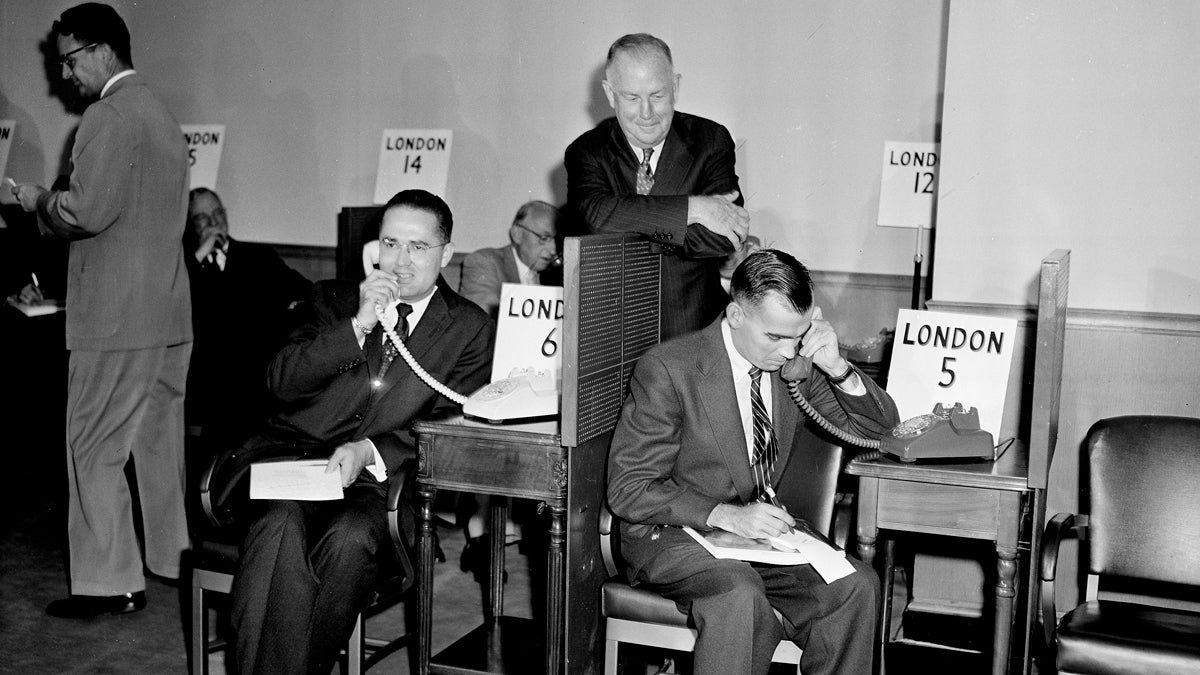

News reporters talk to London as the new 42-million-dollar transatlantic telephone cable is officially opened in New York City

“May I have your attention please? I think it would be desirable now if you would all pick up your handsets and be prepared for the conversations.”

With that polite introduction, Dr. Douglas Bowie, president and general manager of the Canadian Overseas Telecommunication Corporation, launched a new era in the history of human communication this week in 1956.

For the first time ever, people on opposite sides of the Atlantic Ocean would speak to each other directly by telephone.

Electrical communication between North America and Europe was nothing new in the 1950s. A century earlier, retired paper manufacturer Cyrus Field had overseen the construction of the first transatlantic telegraph cable. Technical problems plagued that initial link, but by the end of the 1860s, nearly instantaneous communication had been established across the Atlantic. Additional cables followed, and soon thousands of miles of copper wire crisscrossed the world’s oceans—the backbone of the first global communications network.

These cables were well-suited for telegraphy but not the human voice. AT&T’s engineers learned early on that telephone signals weakened as they traveled through a wire. Vacuum tubes—devices resembling lightbulbs that could amplify electrical signals—enabled the company to overcome this difficulty and construct a transcontinental phone line by 1915.

As telephone service became more popular, some imagined extending phone lines across the ocean. Unfortunately, vacuum tube-based repeaters were fragile, and replacing them would be nearly impossible once a cable was lowered on to the ocean floor. Rather than deal with these issues, people turned to an alternative technology to transmit the human voice: radio. Wireless stations were cheaper than cables but remained vulnerable to eavesdropping or nasty weather.

On both sides of the Atlantic, interest in an undersea telephone cable grew.

Finally in the early 1950s, AT&T allied with the British Post Office and the Canadian Overseas Telecommunication Corporation to turn those dreams into a reality. The planned Transatlantic Telephone cable (TAT-1) stretched over nearly 2,000 nautical miles from Newfoundland to Scotland. The key to its design was an improved repeater, developed by engineers at Bell Labs, AT&T’s research division. Each of the cable’s fifty-one repeaters contained three highly reliable vacuum tubes nestled within several layers of insulation, intended to protect them from corrosion or external damage for at least twenty years.

During the summers of 1955 and 1956, AT&T worked with its partners in Canada and Great Britain to lay the TAT-1 cable. The operation proceeded smoothly, and on September 25, 1956, the transatlantic telephone line was officially opened when AT&T chairman Cleo Craig called Charles Hill, the postmaster general of Great Britain. Hill was pleased to report to Craig and FCC chairman George McConnaughey that “you sound as if you’re speaking from somewhere here in London.”

TAT-1 provided enough bandwidth for thirty-six telephone conversations. It paved the way for the modern fiber optic cables that underlay modern Internet and remained in operation from 1956 to 1978, two years longer than its intended life span.

Benjamin Gross is a science historian and research fellow at the Chemical Heritage Foundation. This post is part of his weekly web series for The Pulse, which takes us back in time to celebrate important moments in science history.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.