The power of failure, and other lessons from a 400-year-old ‘book of secrets’

ListenCould grinding sand help build better scientists?

A group of Columbia University students is keeping a close watch on a bright red liquid swirling in a pot. They keep checking the temperature through masks and protective goggles. Eventually, they declare the liquid to be ready, and dip thin branches into the mixture, creating what looks very similar to pieces of coral.

They have replicated a recipe from a 16th century “book of secrets” a how-to manual from the Renaissance period, which describes art and craft methods that were popular during that time.

“One must first make the branches from wood or take a fantastical thorn branch, then melt a pound of the best possible clear pine resin and add one ounce of finely ground vermilion together with walnut oil,” reads the translated recipe for the imitation coral.

Such books became popular during this time because of a growing interest in increased productivity, and refining of processes.

In photos, the manuscript they have been using all semester looks like something right out of The Da Vinci Code. One hundred and 70 pages are filled with curvy handwriting in faded ink, interspersed with illustrations – sometimes mid sentence – containing as many mysteries as it does clues. Mystery number one is who wrote the manuscript.

“We don’t know,” said Joel Klein, a fellow with the Chemical Heritage Foundation, and a post-doc on the “Making and Knowing” project at Columbia University – which this class is part of. “So that’s one of the things we’re interested in; who wrote it, why were they writing it, where were they writing it. We think it was probably written near Toulouse, but apart from that, we don’t have many clues.”

The original is housed in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris, and is known as Ms. Fr. 640. As part of the Making and Knowing project, PhD students have been meeting at Columbia University every summer to transcribe its original French, and continue to translate it into English.

Making lute varnish and casting grapes from sugar

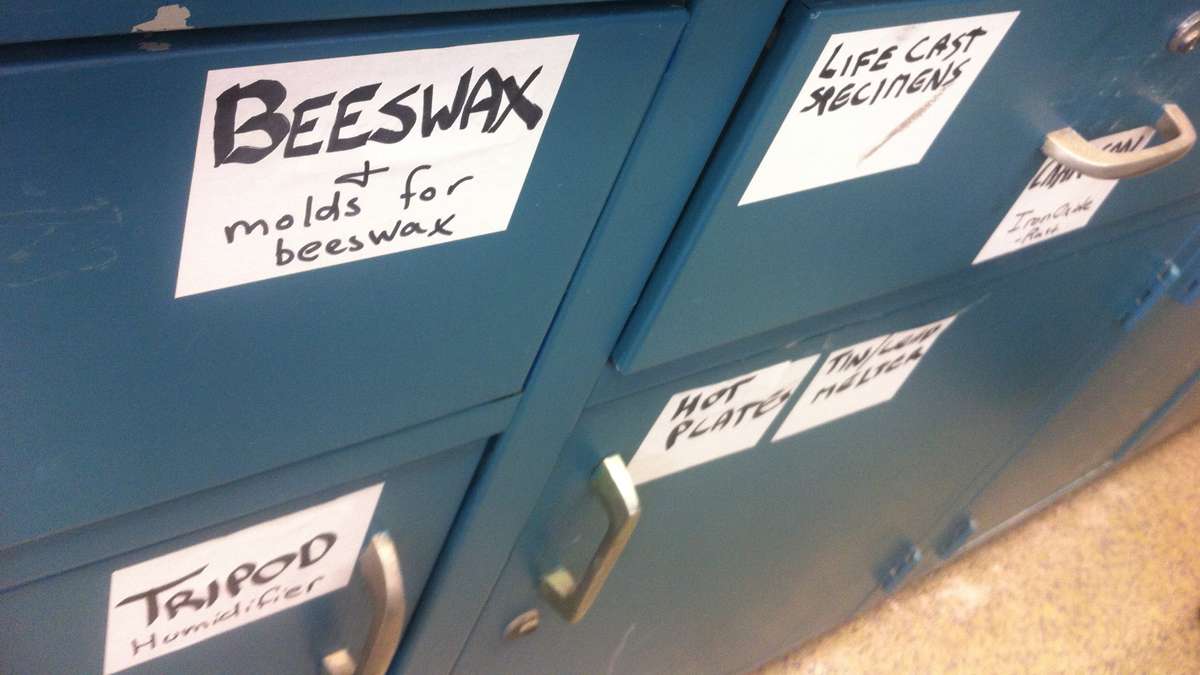

The manuscript contains hundreds of different how-to instructions, everything from casting pilgrim medals to making hourglass sand. Student Caroline Marris has been struggling to re-create a varnish for lutes. “We had two base ingredients: turpentine and lavender spike oil,” she explained. “They were very smelly so nobody in the lab was very happy with us. We mixed them with ground amber, an exotic material for us.”

For the coloring, they added dragon’s blood resin which is red and comes from rattan palm trees, and turmeric powder for yellow hues.

Marris had been applying the varnishes she created to a slab of Spruce wood, but wasn’t satisfied with the results. “If they were layered many times it would be a decent yellow color, but the red didn’t come out at all,” she explained to another student. “We’d have to work a lot harder so that we’d have a strong enough red and a strong enough red powder in the mix.”

At another corner of the lab bench, students Celia Durkin and Sofia Gans were examining a pretty sad looking bunch of grapes, cast from melted sugar. According to the manuscript, they were supposed to cook the sugar until it formed threads when shaking, but they didn’t quite understand what that meant.

“We ended up missing the threads, because we were looking for something other than what it was,” said Gans. “We saw the threads but they didn’t happen when you shake it. It’s when you lift it, so it was very subjective,” added Durkin.

Words will only tell you so much

This limitation of the written word as a tool for transmitting knowledge is one of the important lessons of the class, explained Pamela Smith, a historian of science at Columbia University who heads the Making and Knowing project.

“Think of a cookbook, you can’t put every single action into a cookbook,” she said. “If somebody doesn’t know how to cook at all, it would be very hard to describe to them in the detail needed, that’s a problem of experiential knowledge; you just can’t put everything into writing.”

The need for learning by doing was one of the main motivations for Smith to start this project. She caught the bug of hands-on work in the workshop of a silversmith where she tried to learn a specific process of casting metal objects.

“As a historian of science, of the material world, I was for the first time, actually engaged with materials, instead of books and science,” she recalled. “It was an incredible experience, and I thought this is something that has to be conveyed to my students.”

Students are often puzzled by the lack of exact measurements in the instructions – the author uses ratios and qualitative descriptions of what things should look like.

“It should be thick as mustard, or as thin as the starch that women use for laundry, that is one of the descriptions in the manuscript,” said Smith. “These denotations of consistency are much more useful than measurements of non-standard materials.”

When things go wrong and it’s more than alright

Every student in the lab has experienced a series of failures from pale lute varnish to wooden box molds that caught on fire, and then there was the silver incident.

“We were so excited to pour silver and when we finally did, the silver just exploded everywhere,” recalled Joel Klein. “Our molds were too wet, and this was an important learning experience for us, because the manuscript was pretty clear that we needed to dry our molds more than what we did.”

But Pamela Smith says that failure – especially for students who have so far tried very hard to avoid making mistakes – is a really important part of the experience.

“Failure and then continued experimentation is just part of the process of coming to understand, and that has been occluded and forgotten in our testing culture.”

“Our scientific manuscripts don’t say ‘it took us nine times, to get the liquid phase of the high-performance liquid chromatography machine working,'” agreed Bethany Brookshire, a science writer and educator for Science News and Society for Science and the Public. “Hands on is the only way you’ll get the experience, how hard it is to do things and reproduce them,” Brookshire added.

Pamela Smith says this approach of learning through failure is also visible in the pages of the manuscript. “He couldn’t stop experimenting, he then wrote down all kinds of different ways of doing things in the margins.”

And, it’s also one of the connections between this manuscript and today’s scientific process. “This period in which craftspeople are writing down their processes is also the period where what we know as modern science today is emerging,” explained Smith. “It’s emerging from several different sources, but one is the craft workshop, craft knowledge, the power of productivity, and the power of collective work in the workshop.”

The students are writing scientific papers on their experiments – including their failures, and all of their work is being collected to annotate the original manuscript. Eventually, everything will be available online for other historians , scientists and students to peruse.

And as one of the participants put it – the manuscript and the project stimulate more and more questions – and it inspires students to keep searching for the perfect mold for casting, and the most beautiful varnish for a lute.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.