The grandmother and the bomb builder: How one woman’s search for the truth forged an unlikely bond

For 30 years, Kathy Sanders has sought answers about the terrorist attack that killed her grandsons. She hopes a new piece of evidence will bring her closer to the truth.

Listen 26:14

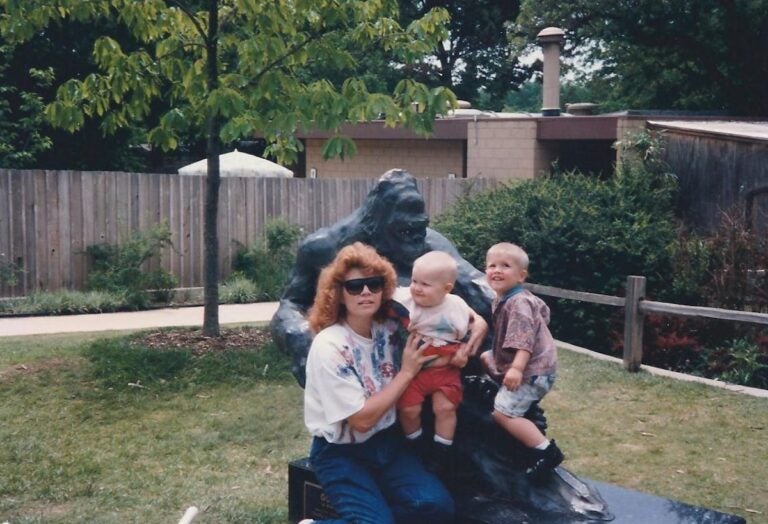

Kathy Sanders lost her two grandsons, Colton (middle) and Chase (right), in the Oklahoma City Bombing terrorist attack. (Courtesy of Kathy Sanders)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Find our full episode on proof here.

On April 19, 1995, Kathy Sanders woke up and walked over to the room where her grandsons Chase, 3, and Colton, 2, slept to wake them up with a song.

Greeting the two boys in the morning was her favorite part of the day.

“ And when I did, I was startled. They weren’t in their beds, they weren’t in there.” Sanders said.

She tried the next room over, where Sanders’ daughter Edye Smith slept, and breathed a sigh of relief.

The boys were snuggled up with their mom.

“When I flipped on the light, I sang, ‘Good morning to you. Good morning to you. We’re all in our places with sunshiny faces. What a nice way to start a new Wednesday!’ And the little boys began to giggle. And Edye and I begin to get the boys ready for school.” Sanders said. “And that’s where they spent the last night of their lives.”

The boys attended daycare at the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City, just a few blocks from where Kathy and Edye both worked downtown.

They dropped off Chase and Colton. Then, at 9:02 a.m., Sanders heard a thunderous roar.

“It was unlike anything I’d ever heard in my life. I knew something bad had happened.”

She rushed downstairs to her daughter’s office.

“Everyone inside her office was lined up, looking out the windows, trying to figure out what happened,” she said.

The mother and daughter sprinted down to the main lobby.

“When we walked out the revolving doors of our building it was like we entered the Twilight Zone. There were big sheets of plate glass falling down all around us. There wasn’t a car moving in the street.”

They saw smoke rising three blocks away in the direction where they had just dropped off Chase and Colton.

“And I said, ‘Edye, the babies!’ She took off running with me on her heels.”

They arrived at the south side of the federal building to the sound of three more explosions.

But the building itself looked normal. Intact.

Subscribe to The Pulse

“We saw more clouds of black billowing smoke. And we ran around to the north side of the building. When we got to the north side, it was the cars in the parking lot blowing up. And then we turned and we looked at the north side of the building. And where the daycare once was, was nothing but a pancaked pile of rubble,” Sanders said.

“My daughter fell to her knees and she began to weep, ‘my babies, my babies.’ And I knew it was the first time in my daughter’s life that she had a problem her mother wasn’t gonna be able to fix.”

Sanders and her daughter spent the rest of the morning as hundreds of other families did — waiting for news.

And it came relatively quickly. The worst news. Chase and Colton were dead.

“ I guess we were some of the lucky ones ’cause we knew that day the fate of our children,” said Sanders. “Some people had to wait days.”

The mother and daughter drove home that night with two empty car seats behind them — their lives changed forever.

“We get home and we don’t know what to do,” said Sanders. “We turn on the TV to continue watching the coverage and they do a closeup view of a little blue sandal that I’d put on Chase just that morning. And I realized, oh my God, his, the shoes were literally blown off his feet. One of the fathers of a surviving child, he’s there by the hospital bed with his boy. And he said,’you know, we just prayed and asked God for a little boy to hold, and God answered our prayer. Isn’t this great?’ Well, for us, that was like a kick in the gut.”

Sanders knew she’d say the same thing if her grandsons had survived. But they did not.

And that made her and her husband ask the kind of questions she thought she’d never have to ask — about God and the nature of good and evil.

But soon, other questions emerged — about the government, the investigation, and what had really transpired on that horrific day.

Those questions started a few days after the bombing, when she organized a dinner at her home for the other families who had lost children at the daycare.

One of the moms mentioned seeing bomb squads downtown in the morning.

The other families didn’t believe her. It just didn’t make sense. How did she know for sure it was the bomb squad?

“She said they had big blue letters on their jackets,” Sanders said. “And my husband was incredulous.”

The next day, her husband, Glenn Wilburn, went to the fire department to ask the chief what he knew about it all.

Was the county’s bomb squad team downtown in the hours leading up to the bombing?

Absolutely not, the fire chief told her husband, said Sanders.

But it wasn’t just that mother who believed she saw something.

Months later, an ABC News investigation found several others had individually reported seeing bomb squad teams before the attack that morning.

Soon the fire chief back tracked.

He admitted the county’s bomb squad truck was downtown that day after all for routine training, but someone had used the truck to make unsanctioned stops for coffee and other errands.

It was an embarrassing coincidence.

“We didn’t know what to believe,” said Sanders.

Because, while some witnesses had seen that truck, that still didn’t explain many of the other bomb squad sightings.

Some reported seeing what looked like armed officers searching bushes near the federal courthouse and bomb sniffing dogs.

Investigative journalist Andrew Gumbel, and his co-author Roger Charles, dug through thousands of pages of records and government reports on the bombing for his book, “Oklahoma City: What the Investigation Missed–and Why It Still Matters.”

Gumbel knows how tricky memory can be — especially for those asked to recall scenes from what would become a giant media event.

But he discovered there might have been something to those sightings.

He found other bomb squad units were also in Oklahoma City that morning.

There was a team from the state, as well as one from the U.S. military sent in all the way from New Mexico.

“I’ve never got to the bottom of why they were sent. I’ve never got to the bottom of what they did, if anything, and at what point they were told to go home,” said Gumbel.

Gumbel confirmed previous reports in the days leading up to the attack that federal agencies and local authorities had exchanged vague warnings that something was up.

“It is not clear if it was a generalized warning against federal courthouses, or if it was a specific warning about Oklahoma City,” said Gumbel. “A lot of those warnings circulate all the time, so it’s important not to put too much stock in that kind of evidence necessarily.”

In the early days after the bombing, Kathy Sanders and her family knew none of this yet.

But they did know some of the details coming out about the perpetrators.

By then, authorities already had Timothy McVeigh in custody.

The skinny 26-year-old anti-government extremist and white supremacist had been pulled over shortly after the bombing.

His getaway car was missing a license plate. On the passenger seat was a manifesto.

Authorities said the bombing itself was not captured by any security cameras that morning.

But McVeigh’s description also roughly fit that of John Doe #1 — one of two men who the FBI said rented a Ryder moving truck under an assumed name from a body shop in Kansas days earlier.

Investigators traced the serial number of the truck’s axle found in the rubble.

Two days later, an accomplice, Terry Nichols, had turned himself in.

Nichols lived in Kansas and was an old army buddy of McVeigh’s.

He had helped load the Ryder truck with two tons of ammonium nitrate and fuel to build the bomb.

But Nichols looked nothing like the other person agents were looking for: John Doe #2 — an olive-skinned man with long hair and a distinct hat first seen with McVeigh at the body shop.

Two dozen witnesses said they saw a man matching that same description with McVeigh in Oklahoma City on the morning of the bombing.

Others described a small caravan of vehicles that appeared to assist McVeigh downtown that morning.

So the hunt for this mysterious accomplice, and anyone else who might have been involved, continued.

It soon became the largest manhunt in American history. But it did not last long.

“In a matter of weeks, [the FBI came out] and said, ‘you know what? We made a mistake. There is no John Doe #2.’” said Sanders.

She was stunned. Could over 20 people all be wrong?

According to investigators, the answer was yes.

The FBI insisted John Doe #2 did not exist and those witnesses were mistaken.

Investigators said the body shop employees who had originally described this figure to the forensic sketch artist had confused this figure with a local customer.

Authorities stated Timothy McVeigh and Terry Nichols were the only people who caused this bombing.

Journalist Andrew Gumbel says prosecutors insisted the case was just that simple — that it had to be.

Prosecutors told Gumbel that they could not fail to secure a conviction, citing pressure from President Bill Clinton and U.S. Attorney General Janet Reno in what was the worst terrorist attack on U.S. soil to date.

“At a certain point in the investigation, they had not been lucky in finding other suspects beyond McVeigh and Nichols, and they decided as a matter of courtroom strategy to focus on them exclusively and to characterize McVeigh in particular as a lone mastermind,” said Gumbel.

That meant no loose ends. No mysterious unexplained John Does.

“You had this very strong narrative from the federal government, but also from state officials, that McVeigh and [Terry Nichols] were the only two significant players.”

Jaded by the bomb squad saga, Kathy Sanders and her husband watched prosecutors lay out this narrative in real time at Terry Nichols’ federal trial in 1997.

They never doubted whether Terry Nichols was guilty.

Still, they listened as his defense attorney poked holes in the idea that he alone collaborated with McVeigh.

“We learned about the Dreamland Motel where McVeigh stayed the week before the bombing. He drove the bomb truck with the bomb in it from the front, from the Dreamland Motel to Oklahoma City and blew up the building,” said Sanders. “Well, while he was at the hotel, there were people seen coming and going from his room.”

People investigators once again said did not exist, despite what multiple witnesses told them—the motel owner, a chinese food delivery man, and other guests.

These seemed like important leads that Kathy and her husband thought were easier to simply dismiss than disprove.

“That was problematic for us. Then we learned that the FBI had gotten good latent fingerprints from McVeigh’s [getaway] car after he was arrested, and from the Dreamland Motel, [and from the Ryder truck rental agency],” said Sanders.

An FBI fingerprint specialist testified that there were 1,034 latent fingerprints from these scenes that did not match the FBI’s list of suspects.

But none were ever run through the FBI’s vast computer database for other potential matches.

“The defense attorneys were like, ‘Well, why in the world wouldn’t you?’ And he very sheepishly said, ‘Well, it wouldn’t be cost effective.’” said Sanders.

“Now as I’m watching all this happen, my heart is so broken. I’m dying, but I’m watching my husband’s anger. He’s mad at God for not saving our children. He’s mad at McVeigh for blowing up the building, and he’s mad at the federal government because he doesn’t believe he’s been given the truth.”

Why was the FBI letting so many leads go? So many other potential suspects who were implicated?

She said she asked one of the lead agents who sat next to her in court.

“He patted me on the shoulder and he said, ‘don’t worry, Kathy. We don’t want to give the defense teams any ammunition to point the finger anywhere else. We wanna get these two convicted and then we’re gonna go after the others.’ And they never, they never went after the others,” said Sanders.

Before the trial ended, less than two years after the bombing, her husband Glenn Wilburn died of pancreatic cancer.

“ I learned from watching Glenn that harboring bitterness and anger and hatred in your heart, it’s like drinking poison and expecting the enemy to die,” she said.

Now, Sanders sat alone in the courtroom, searching for the answers her husband would never know, and her heart started to break for someone else: Terry Nichols’ mother.

“ I realized she’s the forgotten victim,” she said. “What a horrible thing that her son got so messed up in. And it wasn’t long after I befriended her, we began to … eat lunch together, and we sat together in the courtroom. And Terry Nichols, the bomber, became my friend, Joyce’s son.”

She never forgot that Joyce’s son was a terrorist, who helped build the bomb that killed her grandsons. But she started to see him differently.

Not as a monster, but as a person who did something monstrous.

If others had helped him pull it off, they should at least be treated like he was.

A third man, Michael Fortier, eventually admitted to knowing about the plot.

He was not John Doe #2.

But he struck a deal with the feds, testified against Nichols and McVeigh in exchange for only 12 years of prison time and his eventual disappearance into the federal witness protection program.

Nichols was found guilty on one count of conspiracy and eight counts of involuntary manslaughter.

Unlike Timothy McVeigh, he was spared the death penalty and sentenced to life without parole.

“The jury forewoman got on TV and she said, we know Nichols is guilty, but we don’t know how guilty,” Sanders said.

Kathy still had questions too. She returned home from the trial and received a letter.

It was from Terry Nichols.

“And I thought, ‘Lord, I’m not looking for a pen pal, and if I was, it wouldn’t be the Oklahoma City bomber.’” she said.

“And then I thought, well, who’s gonna know more about the bombing than the bomber? So I was willing to dance with the devil to get to the truth. So, I began to write to Terry.”

He asked for her number. He said he wanted to speak with her.

“I gave him my phone number and we began to talk on the phone,” she said. “He was soft spoken, you would never think that the man would’ve done something so horrific. And probably had he never met Timothy McVeigh, he wouldn’t have done anything.”

In 2004, Nichols was jailed close to where Sanders lived, awaiting a new trial on state charges — a final shot for the people of Oklahoma to sentence him to death.

Sanders started to visit him.

“Did I forgive Terry Nichols? Yes, I have,” she said. “Do I think he should be punished? Yes, I do. Forgiveness and punishment are two different things, but I have a friendship with him.”

Nichols didn’t want to die.

He told Sanders that once his trial was over and the death penalty was not hanging over his head, he would tell her everything he knew about the plot.

And soon that day seemed like it had finally come.

Nichols was found guilty on all of the state charges. But the jury could not come to a unanimous decision on the death penalty.

The rest of his life would be spent at a federal maximum security prison in Colorado, where he agreed to let Sanders interview him for a segment that would air on CBS’s 60 minutes.

He trusted her more than any journalist.

The segment would air as a follow up to the show’s interview with Timothy McVeigh five years before.

Then Sanders got a letter from the warden. Her media request to meet with Terry Nichols was denied.

The warden said it “could pose a risk to the internal security of [the prison] and to the staff, inmates, and members of the public.”

“Now, Florence, Colorado is the prison that houses the worst criminals in America,” she said. “How could I possibly be a threat to them or to the guards or to the staff?”

She was eventually taken off his call list, too.

Ever since, the two correspond through letters that are screened by prison officials — unsure whether their full correspondence really gets through.

But Sanders’ search for answers has continued.

She wants to know if there were others who helped McVeigh and Nichols pull off the bombing and what role undercover federal agents may have played in tipping off the bombing a little too late.

“I felt like I, my husband, and [my grandchildren] deserved the truth,” she said. “So I’ve continued the investigation over all of these years. I’ve been to the Aryan Nations. I learned that Timothy McVay was through there and they helped shape his hateful ideas. And that’s a really scary place to go.”

She has collected her own statements, asked her own questions and keeps her own archive.

She’s also written a book about her journey: “Shadows of Conspiracy: The Untold Story of the Oklahoma City Bombing.”

But she still helps journalists when they come calling, like Andrew Gumbel who started to write his book on the bombings in 2001.

“When I came along in 2001, she’d been at it for six years and was able to introduce me to a number of people. That was my starting point,” said Gumbel.

It was a starting point that eventually led Gumbel and his co-author to access the full discovery file that the government had handed over to Terry Nichols’ defense team at trial.

No journalist had ever seen it before. And the file posed more questions than it answered.

Including one extremely confounding question — something Timothy McVeigh’s lawyer made a lot of noise about during his trial.

Not those witness statements or a lack of security camera footage.

But a physical piece of evidence called P-71.

“What happened was that about a month after the bombing, there was a federal agent who found this extra leg in the rubble,” said Gumbel.

It was a left leg with a military boot attached to it.

“And in those days, there was no systematic DNA screening of body parts because it took a long time. And so the forensic experts had to pick and choose what DNA [to test]. So there was no immediate answer to who the leg belonged to,” he said.

It soon became apparent that the leg belonged to a 21-year-old Air Force cadet who was killed in the attack. She had stopped into the federal building to get a social security card for her baby.

“Lakeisha Levy, who in the meantime had been buried in her hometown in New Orleans,” he said.

Her body was exhumed.

“And they confirmed, first of all, that the leg in the rubble belonged to her, but she had been buried with a different left leg,” he said. “So, then the question was, who did that belong to?”

During Timothy McVeigh’s trial, his defense lawyer argued the leg suggested the presence of another bomber. Maybe this was all that remained of John Doe #2.

Prosecutors said it likely belonged to one of eight victims buried without a leg.

Gumbel’s sources within the FBI told him they were confident about this theory, and even narrowed their search down to a single victim.

But the only thing that would settle the dispute was a DNA profile—a sample that could either be matched to a victim or singled out as some unknown suspect.

Decades later, however, in 2015, a spokesperson from the medical examiner’s office told a local news outlet that it actually did obtain a DNA profile from that leg after all.

The spokesperson said the profile was never provided to defense teams, and that it did not match any of the victims it was tested against.

This extra leg has bothered Kathy Sanders since she first found out about it during the trials.

“ Because they don’t know who it is,” she said. “It could be a bomber, we don’t know.”

Then Terry Nichols told her it was crucial.

“If you really want to get to the bottom of the OKC bombing,” he wrote to Kathy in one letter, “then do a genealogy test on that leg.”

Nichols suggested using modern science to crack the case: forensic genetic genealogy.

It was the same technique that led to the apprehension of the Golden State Killer in 2018 — using public DNA databases built from consumer ancestry testing kits to identify a suspect’s relatives based on their DNA profile.

From there, it’s just about focusing in on an individual suspect, like shrinking a haystack to find a needle.

So Sanders recently called up the medical examiner’s office and filed a request for a copy of that DNA profile.

“Why couldn’t we have run those through a database? You know, if you’ve got the science and aren’t allowed to use it, then you’re just up a creek,” Sanders said.

The office said it could not provide her with the sample, citing a law that requires requests only from “interested parties”.

Someone like a defendant in the case.

Someone like Kathy’s unlikely ally: Terry Nichols.

“I’m in the process of working with an attorney and I’m taking some new steps that I can’t talk about right now,” she said. “But I’m not giving up. It’s been 30 years. And I’m gonna find out who that leg belonged to.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.