Temple scientists hit Gulf of Mexico to explore human-generated deep-sea acidification

Listen-

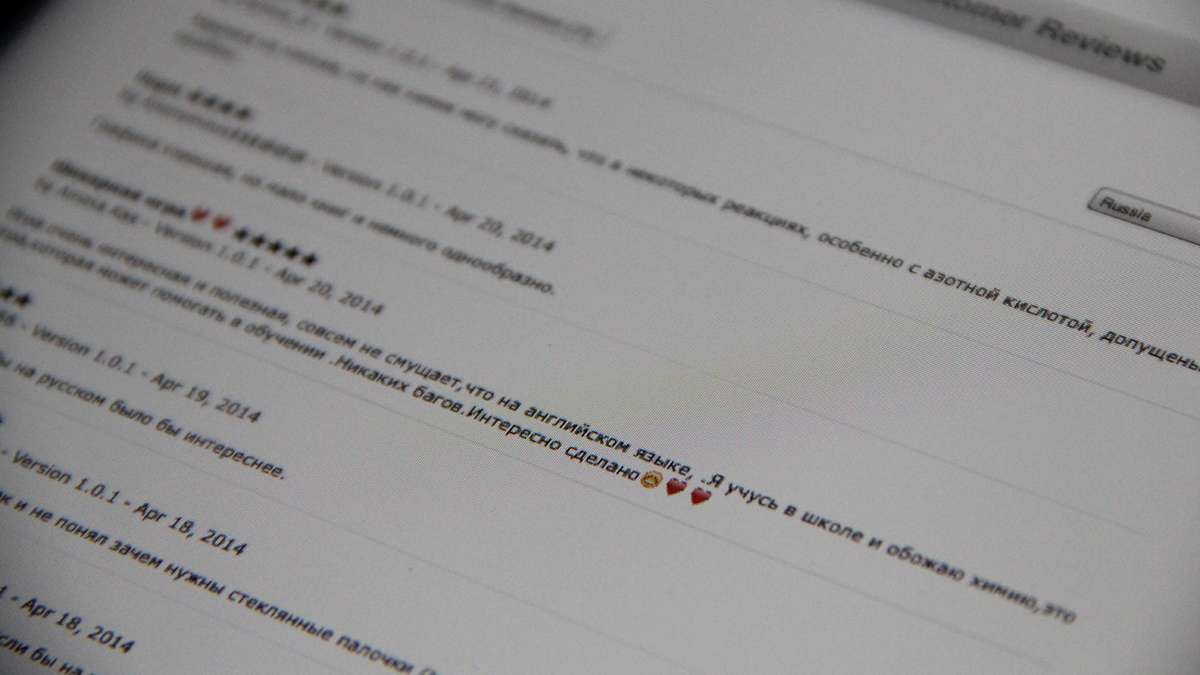

The ChemCrafter app has had unexpected success in Russia. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

ChemCrafter users can unpack chemicals similar to those used in vintage sets popular in the 1940s and '50s. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

The Chemical Heritage Foundation's Shelley Geehr headed up the app project. Designers of ChemCrafter found inspiration in the foundation's large collection of vintage chemistry sets. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

The look of the ChemCrafter app is inspired by vintage chemistry kits from the 1940s and '50s. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

-

Dr. Erik Cordes is shown climbing into the Alvin submersible in 2010. (Photo courtesy of Helen White)

-

Temple University scientists are embarking on a three-week cruise to search for clues on ocean acidification and its impact on deepwater coral reefs.

Scientists from Temple University are about to head out on a three-week research cruise into the Gulf of Mexico. Their goal? To look at how carbon dioxide is impacting organisms such as deepwater coral reefs down on the ocean floor.

The Pulse’s Maiken Scott sat down with lead researcher Erik Cordes to find out more about ocean acidification and life in the Alvin submersible. Here are excerpts from their conversation.

So tell me about this mission you’re about to embark on.

This is a voyage out to the middle of the Gulf of Mexico on the research vessel Atlantis with two submersibles — the Alvin submersible, which is one of the most famous ones in the world, and an autonomous underwater vehicle, which is a really new type of technology, called Sentry.

So what is the goal of your mission?

This is a three-year project funded by the National Science Foundation to look at the effects of ocean acidification. We are specifically looking at ocean acidification and its effects in the deep sea, which is something that’s really been understudied.

And ocean acidification is thought to be a byproduct of climate change?

Yes. About half of the CO2 that we’re dumping in the atmosphere ends up in the oceans, and what that does in the oceans is, it’s basically making soda water. As you bubble CO2 through it, it becomes an acid and lowers the pH of the seawater and this makes the seawater become corrosive to any organisms that lay down a skeleton or a shell made out of calcium carbonate. So that can be anything from oysters and clams and muscles, to the phytoplankton that form the base of the food chain, to corals and coral reefs. And that’s what we’re studying — coral reefs in the deep sea, which not a lot of people know about to begin with, and then the effects of this human-generated process of ocean acidification in the deep sea.

How deep do you go?

On this mission, we’ll be going anywhere from about 500 meters to about 1,500 meters, so as deep as about a mile. I’ve personally been about two miles down with Alvin.

So, what’s that like?

It’s an amazing experience. It’s one of the coolest things that I’ve ever done, and I actually get to do as part of my job, which is pretty remarkable. It’s exciting. The best thing is you never know what you’re gonna see when you get in the sub and every dive is unique. Every dive you get to see something that no one has ever seen before. There are very few experiences you can have where you can say that. The first time I was in Alvin, I got kind of claustrophobic. It’s only about six feet in diameter inside and there are three of you in there and they seal you in from the outside.

Describe the way down.

They seal you in on deck and then you hit the water and you’re rocking around a little bit. You can feel the waves moving. As soon as you get below the surface, all that motion goes away and it’s still and it’s quiet and you’re slowly sinking down. Everything gets darker and darker around you as you descend and as you get a couple hundred feet down, it gets almost pitch black and you know you’re leaving the surface world when that happens. It’s really a pretty magical thing. If the pilot’s not working, you get him to turn out all the lights and everything you bump into on the way down glows. It causes this bioluminescent reaction and this greenish light comes up and you can stare out the window and see all these little, tiny organisms like stars slipping past the windows. It’s really a beautiful experience.

And how do you collect samples while you’re down there?

We bring a lot of custom sampling gear with us. We equip the front of the sub with all boxes and tubes and cords. Alvin has two manipulator arms, so it can pick up our sampling gear, collect mud or pieces of coral, which is one of the primary things we’ll be doing, or water samples so we can tell the water chemistry down there and then at the end of the dive when you’ve loaded all that gear up, you come back up and then the work really begins for all the scientists on the ship.

How long do you stay down there?

It’s usually about six to eight hours so you get in the water right after 8 a.m. and you come up in the end of the afternoon around 4 p.m. or so.

And you dive every day?

Not me, personally. It’s exhausting, actually. You wouldn’t think that sitting on your butt for eight hours would be exhausting, but it really is. I’ll probably go a few times, but we try and get everyone in. The Alvin dives every day, weather permitting and other contingincies.

And you’re totally on top of each other, right?

Yeah, it’s a really small space and you’re working literally elbow to elbow. The new Alvin — which I’ve never been in — just went through a three-year overhaul process. It’s very different inside and it’s a little bit bigger — a few inches in diameter, which doesn’t sound like a lot but it’s actually a pretty big volume. There are now five viewports instead of three. You can actually get right up next to the pilot and see what they’re seeing.

What’s the shape of the Alvin? I somehow am picturing it to be round but that’s probably silly.

What you sit in is round, it’s a perfect sphere. That’s the best way to keep the pressure out. But the structure around it is kind of oblong and you have this little tail at the end with a propeller — sort of your prototypical submersible.

Is there a bathroom?

I always get this question. There is a bottle and you get two and everyone has their own and there’s a female adapter that looks something like a triangular funnel. And everyone sort of turns around and looks out the window for a minute and pretends not to be listening. Some people try to dehydrate themselves and not pee in the sub, but I really think you should just do what you do.

So what have you found so far in terms of the science. Can you say anything about what is happening on the ocean floors?

We conducted a few studies over the past few years and we were actually really surprised at our results. We found these deepwater corals — Lophelia is the name of the species — form large coral reefs just like you would see in shallow water but they’re down hundreds of meters where there’s no light and they’re totally cut off from photosynthetic productivity. They’re reliant on everything raining down from the surface. But what we found in our previous studies was that these deepwater coral reefs are surviving at lower pH values than any other reefs on Earth. What we’re going out to see if we can discover is how they’re doing that. What is it that allows them to survive under these incredibly harsh conditions that shallow water corals would die under and if we can figure out how they’re doing that, how they’re able to still calcify and lay down their skeleton and survive under this acidification, we might be able to find some key to being able to save some of the shallow water coral reefs to see if maybe some of the shallow water corals could adapt to ocean acidification and survive the way that Lophelia is surviving.

Could you also be creating sort of a baseline in terms of understanding what’s even there and how things are now so you can go back in 10 years and check on it again?

Yeah, so that was one of the big results from a few years ago. We were really surprised at what we found at how low the pH was already and that was when we really established the baseline, but that was only a few years ago. When we tried to go out and study Lophelia to begin with, we did our research and looked around at all the literature around acidification and no one knew anything. There are these global models that try to predict what will happen in the future and how climate change is affecting all these habitats and the Gulf of Mexico, as a whole, was not included in them. Which is really amazing considering all of our economic interests and the proximity to the U.S. and all of these vested interests we have, no one had done this basic research. When we got some results, we were really surprised at what we had found.

Have the levels changed again since your initial research?

That’s one of the things we’re really going to find out. If they have gone down in the last few years, we may be facing a more serious issue.

Is this your last trip? Will this complete the research cycle or how many more are there?

It never ends, I hope, as long as I’m funded. This is probably my only trip this year. I’m waiting to hear about another one but this is the only one that’s affiliated with this research project, specifically, so the stakes are high. We have to get everything done that we planned to get done on this one cruise.

Do you think people are getting the importance of this kind of research? We hear about all these different problems as they relate to climate change and sometimes it’s hard to process it all and how it all fits together.

It is hard to process. It’s hard for me to process at some times. A lot of times it’s hard to be hopeful when you’re confronted with these different problems but I really think you do have to stay hopeful, I think there are solutions. I think that’s one of the things I like about this project and what we’re going to do is we’re looking for solutions, we’re not just going to document a problem. We really are trying to find hope for saving corals in the future and that’s really what I like about it and what keeps me moving. It is hard to convey some of this to the general public and to make them understand the significance of ocean acidifation. You think ‘oh that’s not a big deal it won’t affect me’ but oyster hatcheries are having trouble in Washington, it’s going to change the communities of plankton and it’s going to affect the base of the food chain.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.