Sleep habits may have helped humans branch off from other primates

Listen 5:42

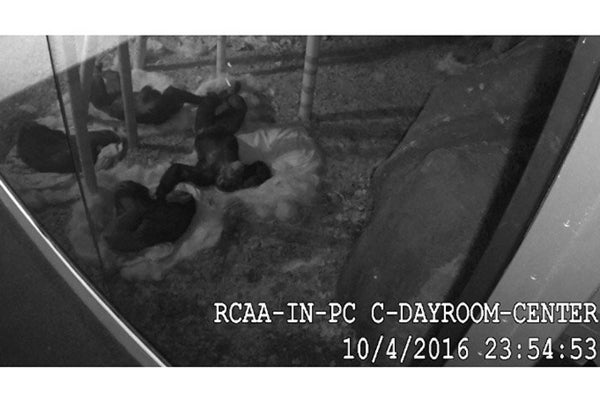

A sleeping chimp at the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago. (Photo courtesy of Lydia Hopper, Assistant Director, Lester E. Fisher Center for the Study and Conservation of Apes)

Human sleep behavior is different than that of many kinds of primates. That made researchers wonder, why did our branch of the family tree evolve differently?

From tool-making to socializing, scientists look to our primate ancestors to better understand our own human habits.

The same goes for sleep, but human sleep behavior is different than that of many kinds of primates. That made researchers wonder: Why did our branch of the family tree evolve differently? What’s the evolutionary advantage of our sleep patterns?

One place experts are seeking answers is the Lester E. Fisher Center for the Study and Conservation of Apes at the Lincoln Park Zoo in Chicago.

Visitors to the primate house, which extends from the zoo’s Regenstein Center for African Apes outdoors onto the surrounding grounds, can watch the study subjects just like researchers do.

Maureen Leahy, curator of primates for the zoo, points across the circular enclosure ringed with people watching the animals. “Right now where I’m standing, Hank, Nana, live in the enclosure across the way,” she says.

“Also in that group is an adult female named Cashew, and she is one of our most impressive nest builders,” Leahy says. “I sort of relate it to ‘Princess and the Pea,’ sort of folding in every single material that you can find into this tall, elaborate nest. It’s impressive.”

Cashew does her elaborate nest-building for the same reason we use pillows and blankets and mattresses — to be comfortable and get a better night’s rest.

“We know from some of our research here that chimps like to sleep next to their friends,” scientist Katie Cronin says as a chorus of chimpanzee vocalizations erupt behind her. She does overnight studies at the zoo to better understand primate life after dark.

That nighttime social behavior and other characteristics of primate sleep are the kinds of things experts like Cronin pick apart because they’re clues to our own evolutionary past.

Cashew, the expert nest-building chimp, is a great ape and in the same family of primates as humans.

“Of about 200 species of primates, there’s only a few great apes species,” Cronin says. “Gorillas, orangutans, chimpanzees, bonobos, and humans, and we’re the only nest makers, so something’s changed over time.”

Whatever drove that kind of change in sleep behavior may have ultimately helped make us the humans we are today.

Coming down from the trees

To try to figure out what forced those changes, it helps to think about what was going on about 1.8 million years ago.

“The advent of our genus homo. This is when humans became human, essentially,” says David Samson, an evolutionary biologist with the University of Toronto Mississauga.

At about that time, our ancestors started to look more like modern humans, which meant they were no longer built for sleeping in trees.

“At that point, by necessity, we needed to be on the ground full-time,” he says.

This is different from how other kinds of primates were sleeping then. Owl monkeys, for example, are nocturnal tree-sleepers who are only awake about seven hours out of the day.

“These are the marathon sleepers of the primate order,” Samson says.

Both the amount and the way owl monkeys sleep — often huddled in groups or hanging from trees — is in contrast with human behavior, and not exactly conducive to deep, meaningful rest.

Samson says this results in a much more fragmented sleep, wherein monkeys and lesser apes wake up frequently and don’t often achieve deeper levels of rest, like the REM states humans enter multiple times a night.

“I guess the analogy would be sleeping coach or economy and sleeping first class. I think great apes are first class sleepers,” he says. “We can sleep in reclined, relaxed positions.”

And reclined, relaxed positions help us get more out of less shuteye than anyone else in the primate kingdom.

Samson was able to demonstrate this in a study he performed involving orangutans at the Indianapolis zoo.

“I manipulated their sleep environments,” he says. “We either gave them straw or a host of different materials.”

And maybe it’s no surprise, but the orangutans that were given things like pillows, blankets, sheets, cardboard, and memory foam to make their nests got better sleep.

Samson found that, when he and his team gave the orangutans those sleeping materials to build complex nests, they actually performed better on touch screen cognitive tests.

So, according to Samson, the link between sleep and cognition is there for all great apes, including humans.

But the unique sleep behavior that helps make us human is a little more complicated than making nests to get better rest.

Sleep as an evolutionary driver

Biologists can tell just based on our size that we should be sleeping differently.

“Humans in fact should sleep around 10.3 hours out of the day,” Samson says. “But we don’t. We sleep on average about seven hours out of the day.”

That’s less than any other primate yet recorded.

“It’s an indicator that something interesting is going on with our lineage in particular,” he says.

Somewhere along the line our ancestors started to develop sleep behaviors that allowed us to get very deep sleep in shorter windows of time than other apes.

“And it’s been a prerequisite for a lot of the higher level cognition we see in these species,” Samson says.

So what were our ancestors doing almost two million years ago that was so different from other primates?

There were probably a variety of things happening that helped us achieve deeper sleep in shorter windows of time. Acclimating to sleeping on the ground was one of them.

“Bringing it all together, it was that transition from the vagaries of sleeping in trees, coming down to a more stable environment,” he says.

Sleeping in groups also allowed some people to keep watch overnight so others were protected from predators during the most vulnerable hours of deep sleep.

Samson says these behaviors set in motion not just changes to sleep behavior, but also, in some ways, the beginnings of humanity.

“You would’ve had a secure sleep site where you could get deeper sleep and then this frees up activity during the 24-hour period for more important things,” Samson says.

That includes daytime activities like hunting, socializing, making plans, and developing culture.

There’s even a theory that intense dreams that happen in REM sleep — which we get more of than any other primate — played an evolutionary role in priming us for the threats of waking life.

All of these factors could have helped us evolve our special sleep behaviors, which may have driven us to have the brains that we do — which allow us to even ponder questions like this.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.