Skepticism in medicine turns 500

Listen

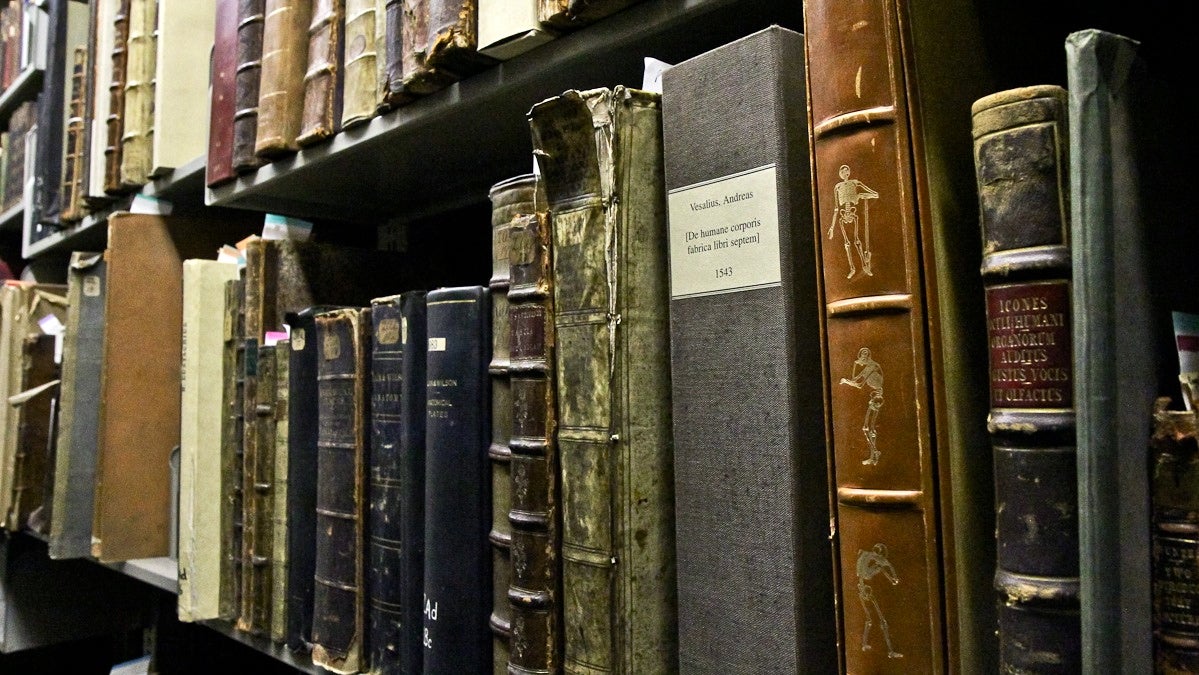

Andreas Vesalius published De Humani Corporis Fabrica in 1543. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Five centuries ago, a small Flemish man changed medicine forever.

Andreas Vesalius was born in Brussels in 1514. He was thought to have some form of dwarfism, but in his professorship in Italy at the turn of the Renaissance, he managed to shake up the very core of medicine, paving the way for how doctors today have come to understand the human body.

Oh, and he did this all before he was 30.

Oh, and he did this all before he was 30.

Instead of turning to ancient texts for insight, Vesalius looked to the body itself for wisdom, and with that, called out and corrected centuries of accepted mistakes. He noted this in a massive anatomy text, De Fabrica (translated: On the fabric of the human body), though he faced quite a bit of backlash when he published it in 1543.

Five hundred years later, museums, medical groups and even illustrators are celebrating Vesalius’ legacy at exhibits and events around the world. It’s a legacy, though, that many say extends well beyond his book and pervades much of modern medicine.

“What Vesalius does in many ways is teach us that the things we take for granted as absolutely true, in reality they may not be,” said Dr. Salvatore Mangione, director of history lectures at Thomas Jefferson University’s Sidney Kimmel Medical College.

Through establishing a hands-on, observational approach for understanding the human body, Mangione and others say Vesalius helped found modern anatomy and establish an essential part of science: skepticism.

A perfect storm

Vesalius rose to fame during an “extraordinary time,” according to Jacqui Bowman, director of education at Philadelphia’s College of Physicians.

It was a time of intellectual freedom, of the printing press. It was a time of great minds like Copernicus, who were really trying to examine the world around them (and in his case, realize that the earth revolves around the sun, and not the other way around).

All in all, it was “a perfect storm,” according to Mangione.

Vesalius came from a very well-to-do family—his father a pharmacist to Charles V—and he went to Italy, to the University of Padua to study. Italian-borne Mangione refers to it, “the Harvard of the time.” Galileo, for example, would later teach physics there. William Harvey, founder of human physiology and circulation, would also emerge from there.

A revolt in anatomy lab

Vesalius does so well that upon graduation, he immediately gets appointed chair of anatomy and surgery. And, as a young professor of medicine, he wastes no time uprooting classroom traditions and beliefs.

“I think it may be safe to refer to him as a bit of a rebel,” said Beth Lander, a librarian at Philadelphia’s College of Physicians, home to the oldest, independent medical library in the U.S and host to a new exhibit on Vesalius. “He liked to do things his own way.”

Mutter librarian Beth Lander leads the way to the Vesalius book in the museum. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Mutter librarian Beth Lander leads the way to the Vesalius book in the museum. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

The old way of doing things involved looking to books to understand the body. But those books, written a thousand years earlier by a man named Galen, were based on animal models. And during that time, 180 A.D., neither the Greeks nor Romans approved of dissecting humans. Instead, Galen likely relied on dissection dogs, cats and apes.

Around the time of Vesalius, the church was beginning to open up. A pope had studied medicine. Great artists like Leonardo and Rafael received permission to dissect humans for their paintings.

“It was not something that you could really brag about, but you could do it,” said Mangione.

Vesalius, however, takes dissection to a whole new level, using his wealthy connections to bring in lots and lots of cadavers for examination in the lab (specifically, he was granted permission to use the bodies of criminals).

Vesalius, however, takes dissection to a whole new level, using his wealthy connections to bring in lots and lots of cadavers for examination in the lab (specifically, he was granted permission to use the bodies of criminals).

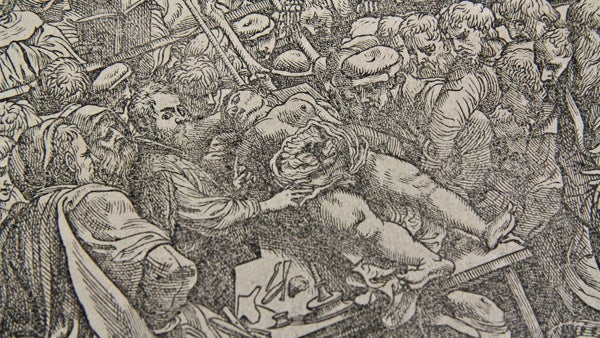

But when Vesalius does this, he ignores all of the dissection protocols at that time—students were supposed to watch as a designated dissector led the process. A lector, meanwhile, would read explanations about what was happening. Vesalius instead encouraged students to participate, in many ways creating the foundation for a class that’s nowadays considered a rite of passage into medicine: first year anatomy lab.

“Andreas Vesalius was really the original hands-on learner guy,” said Bowman. “He wanted everybody to learn by observation.”

The groundbreaking text

In looking directly to the body instead of following the Renaissance tradition of assuming information in books was correct, Vesalius found hundreds of mistakes made by Galen, ranging from the depiction of the mandible to the liver.

“Then once you prove that somebody untouchable like galen is wrong, then the whole thing collapses,” said Mangione.

While he never challenges clinical practices and the Galenic theories that dictated treatments at that time, Vesalius published these findings in 1543 in a massive 600-plus page book called “De Fabrica” or On the Fabric of the Human Body.

“It literally means ‘factory,'” said Mangione. “But I think what he was talking about is the machine. The human machine.”

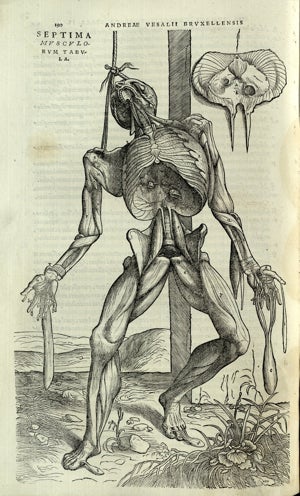

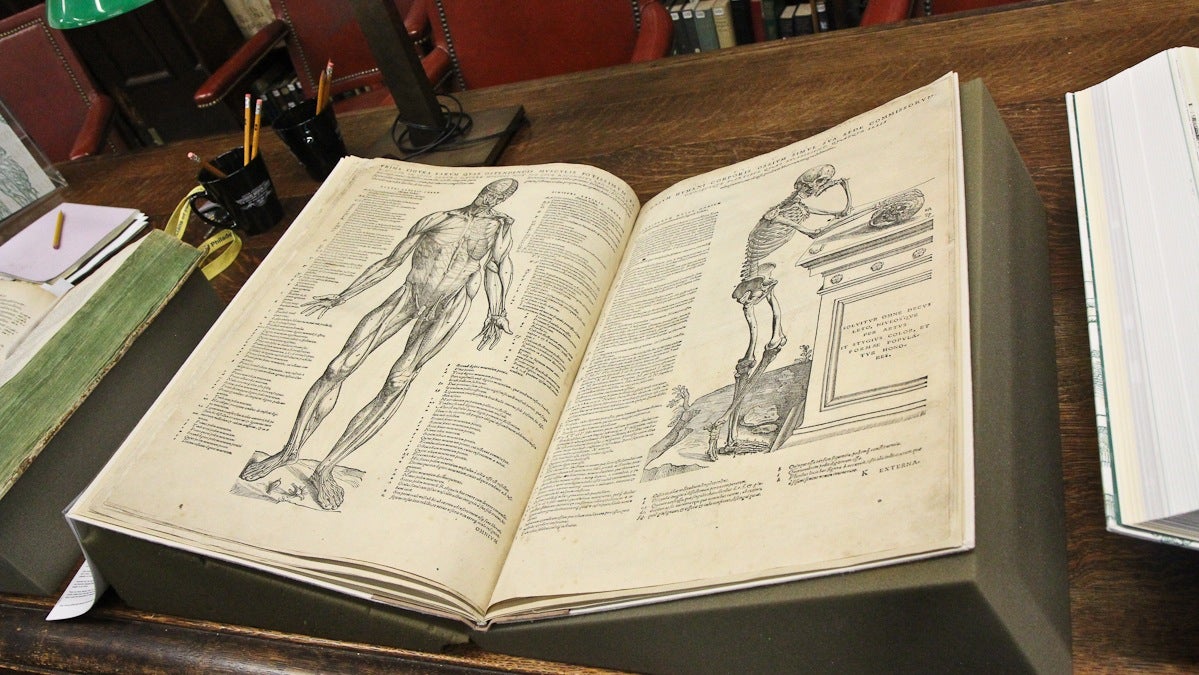

The book contains seven sections, with each one peeling back another layer of the body. Vesalius wrote comprehensive descriptions of the body’s physical structures in Latin.

During the dissections, however, he also had an artist at his side. He turns to woodcarvers in nearby Venice, “the best in the field,” to make woodblocks out of pear wood.

As a result, accompanying his detailed texts are 270 stunning woodcut illustrations of the human body.

“It’s amazingly beautiful,” said Mangione. “The boundaries between art and science blur.”

To Bowman, the pictures capture something else, something truly human.

“There’s a respect for the subject and a wonder, a kind of really seeing how the human body is such an extraordinary, beautiful thing,” said Bowman. “I think [that respect] is sometimes lost these days in medical activities.”

Bodies are often poised in human ways in De Fabrica. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Bodies are often poised in human ways in De Fabrica. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

The bodies are often poised in very human ways. Bowman immediately points to an illustration of a skeleton posed like Rodin’s iconic sculpture “The Thinker”: “This one, he really looks like he’s thinking, wondering what is this skull I’ve got my hand on?”

The bodies are also set against quaint Italian backdrops, of the rolling hills and rivers of Padua.

“It’s like a beautiful landscape, and you just happen to have a man almost, like, signaling to a friend. He just doesn’t have any skin.” Bowman said. “You know, the buttox have been flayed out.”

A struggle to see

In his book, Vesalius makes it a point to document through text and illustration how Galen incorrectly depicted the human body.

And throughout the book, Vesalius mentioned the ancient Horace phrase “nullius addictus iurare in verba magistri,” or “given to swearing by the words of no master,” no fewer than six times, according to Northwestern professor Daniel Garrison, who recently co-authored a new English translation of De Fabrica.

But as defiant and scientifically accurate as the text was for that time, it’s not perfect. Vesalius made some big mistakes, including ones that might be considered obvious, like the entire female reproductive system. He also drew some body parts that Galen had noted, body parts that didn’t exist.

But Mangione says breaking out of a mold of what others had been trained to accept and see for hundreds of years wasn’t easy to do. Vesalius himself recognized his shortcomings, making corrections with each reprint.

“There’s a beautiful quote by Vesalius. At the beginning, Vesalius was buying it, even though he couldn’t see it, what Galen was writing,” said Mangione. “And he actually talks about this network of vessels…at the base of the brain. It was the foundation of the Galenic theories. And he says ‘I couldn’t really see it, but I still put it in the books, at the beginning in my writings. Because it had to be there.'”

Eventually through really observing what he saw, Vesalius began making the switch. And it’s actually in that process, that struggle even, that Mangione, Garrison and others says rests Vesalius’ biggest contribution to science: challenging dogma.

The title page illustration depicts Andreas Vesalius uprooting the old way of conducting an anatomy lesson. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

The title page illustration depicts Andreas Vesalius uprooting the old way of conducting an anatomy lesson. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

“He’s the first to say, ‘The emperor has no clothes,'” said Mangione, who often refers to Vesalius as medicine’s first iconoclast.

He drives home “the all-important message of skepticism that was to become a central, defining tenet of the Scientific Revolution in the subsequent century,” said Garrison.

It’s an a notion that would help lay the foundation for the scientific method.

Mangione says he thinks about this legacy a lot as he teaches physical diagnosis to new students. What, he asks them, are they being taught to see? But, he asks them, what are they really observing?

“We tell medical students that the magic word in science is bullshit,” said Mangione. “I mean, you really have to challenge anything that comes before, and you have to demonstrate that indeed it is accurate.”

The backlash

Vesalius’ actions didn’t come without a price.

The medical establishment did not embrace what he did. Mangione said the response was likely compounded by Vesalius’ brash, arrogant personality.

Mangione points to one particularly emotional attack from Vesalius’ former professor, who said, “I implore his Imperial Majesty to punish severely as he deserves, this monster born and bred in his own house. This worst example of ignorance, ingratitude, arrogance and impiety. To suppress him, so that he may not poison the rest of Europe with his pestilential breath.”

Vesalius supposedly burns his notes in frustration and drops out of academia shortly thereafter, moving away to work as a physician for the King.

Later for circumstances unknown, according to Garrison, he goes on a pilgrimage to the Holy Land, something the church could force upon a person.

Vesalius didn’t survive the trip back. He likely died of scurvy or starvation after a shipwreck in 1564.

The celebration…500 years later

Vesalius may have been forgotten during his day, but this past year has marked an “annus mirabilus” (or “year of miracles”) for Vesalius on the quincentennial of his birth, says Garrison. Philadelphia’s College of Physicians is one of dozens of places around the world honoring Vesalius at special events and exhibits this year and next.

Mutter librarian Beth Lander (left) and Jacqui Bowman, director of Education and Public Initiatives, page through the museum’s rare copy of De Humani Corporis Fabrica. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

Mutter librarian Beth Lander (left) and Jacqui Bowman, director of Education and Public Initiatives, page through the museum’s rare copy of De Humani Corporis Fabrica. (Kimberly Paynter/WHYY)

“You never get to celebrate a 500th birthday, hardly ever, so I figured we have to do something,” said Bowman.

The college has put out their own, 1543 copy of the Fabrica at its Mutter Museum as part of a history of anatomy exhibit.

“It is one of the things that when I first started working here, I took it [the Fabrica] off the shelf in silence,” said Lander, the librarian at the College of Physicians. “I opened it and kind of bowed before it because, as a librarian and as a book freak, it is just an extraordinary thing to behold.”

In classic Mutter style, the museum is also doing other things like recreating Vesalius’ dissection table.

Bowman and others say Vesalius might not have received much acknowledgment when he was alive, so she and others are trying to make his 500th birthday a big deal.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.