Paying tribute to the women who helped integrate Pennsylvania’s health care system

Listen-

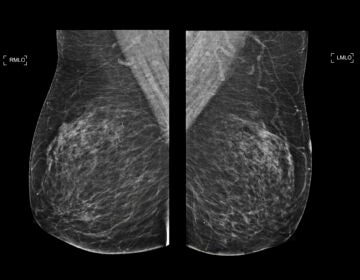

Mercy Douglass' graduating class of 1960 (Photo courtesy of Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing/http://www.pinterest.com/nursinghistory/mercy-douglass-son/)

-

Dr. Jean Whelan, assistant director of the Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing, adjusts a pin on a Mercy Douglass nursing cape at the center's exhibit on the school, which trained black nurses for a segregated health care system. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

Mercy Douglass Alumni Association President Elizabeth Williams greets a former classmate at a tea honoring graduates of the historically black nursing school. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

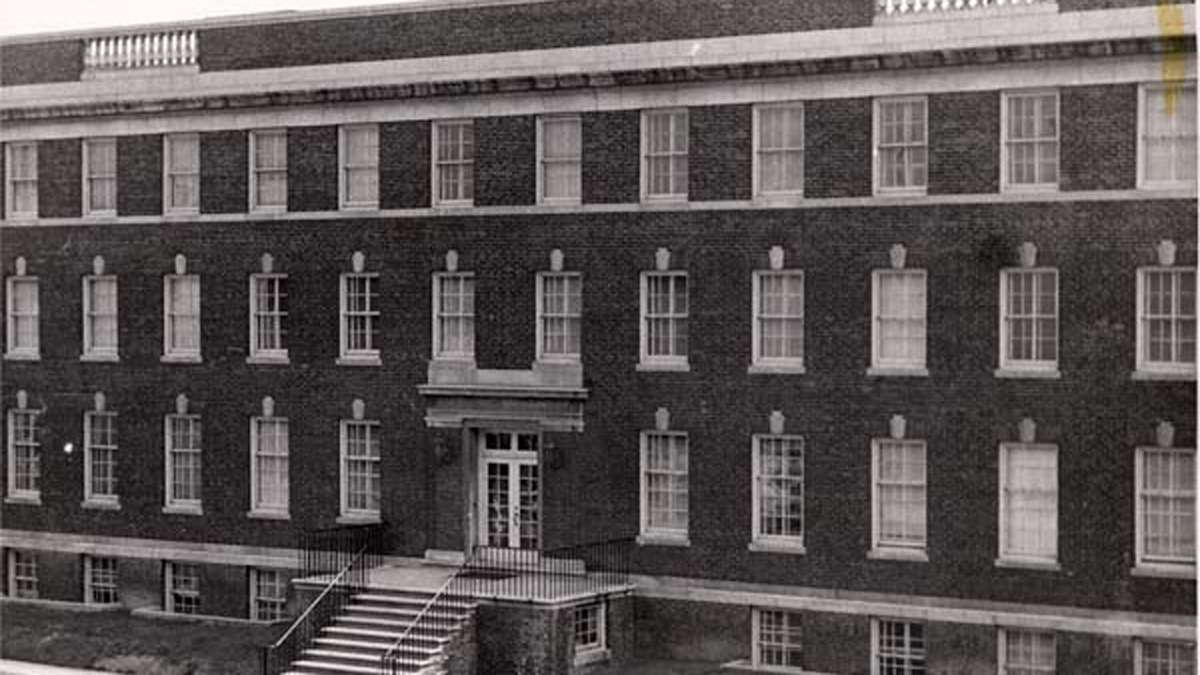

Mercy Hospital (later Mercy-Douglass) was housed in this structure from 1919-1948 and was located in West Philadelphia. A modern nine-story building replaced it in 1955. (Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing/http://www.pinterest.com/nursinghistory/mercy-douglass-son/)

-

Photographs and mementos from Mercy Douglas School of Nursing are on display at the University of Pennsylvania. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

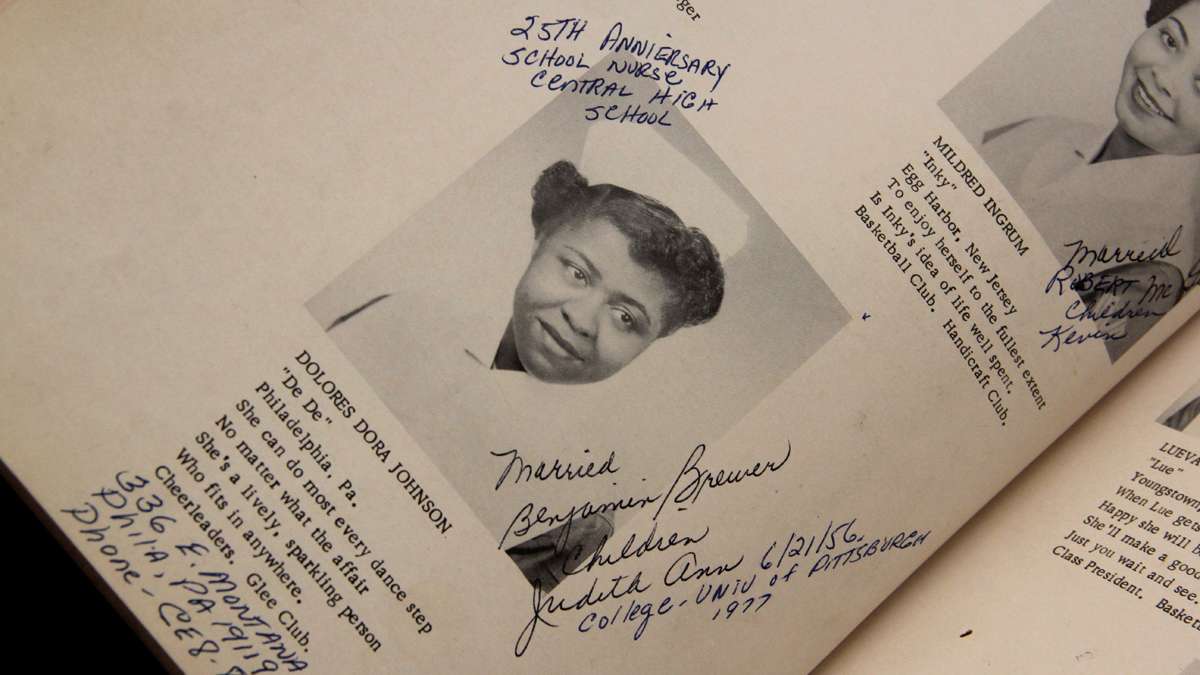

Dolores Johnson Brewer as she appears in her 1952 Mercy Douglass yearbook. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

Mercy Douglas School of Nursing alumni renew old friendships at a tea in their honor at the University of Pennsylvania. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

Dolores Johnson Brewer, Class of '52, brought her yearbook, ring, and pin from Mercy Douglass School of Nursing, to share at a tea honoring alumni of the historically black school. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

Dolores Johnson Brewer, Class of '52, wears her class ring from Mercy Douglass School of Nursing. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

-

Julie A. Fairman, director of the Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing, speaks to alumni of Mercy Douglass School of Nursing during a recent tea at the University of Pennsylvania. (Emma Lee/for NewsWorks)

Alumnae from the Mercy-Douglass School of Nursing returned to Philadelphia recently to remember their time together in the 1940s and 50s.

Delores Johnson Brewer was 18 and in the class of 1952 when she started nursing school.

“We were carefree,” said Brewer, who is 82 today. “Sometimes if you didn’t do what you were supposed to do, you’d be campus bound. We’d go up on the third floor and jump Double Dutch; you could hear it throughout the whole building.

The nursing students lived together in dorms just behind the hospital at 50th and Woodland. They stayed busy with classes, training and mandatory study hall every night until 9 p.m. Students were supposed be in by 10 p.m., but someone was always willing to break curfew to go grab a hoagie, some ice cream or a smoke.

Elizabeth Keys Williams says the House Mother was never far away.

“Mrs. Randall was a big lady,” Williams said. “She’d put her hands on her hips: ‘I smell smoke up here in this hall,’ and we’d all be scurrying like little mice.”

The women found time for fun, but Williams, who grew up in Steelton, Dauphin County, says her parents didn’t send her all the way to Philadelphia to play around.

Her father was a chauffer; her mother worked as a cook.

“She wanted something different for me,” Williams said. “I think it cost us like $450 for the three years that I went there. Believe it or not, it was a challenge for my parents to get that money together.”

Brewer considered nursing schools at Episcopal and Pennsylvania hospitals but she says those programs only made room for two black students. Their quota was filled, Brewer says, and the schools told her: ‘Try again next year.’

“It was segregation,” Brewer said. “That was the ways of the world; you just accepted it.”

In America, nearly everything was separate: Where you ate. Where you lived. Where you learned.

Black doctors founded the two hospitals that eventually merged to become Mercy-Douglass. In the 1940s and ’50s, the hospital’s school of nursing was a training ground for young women looking to launch a professional career at a time when opportunities for African Americans were very limited.

The University of Pennsylvania hosted the alumni tea, and for several years, has been gathering photos, transcripts, letters and stories from the African American women who attended Mercy-Douglass.

“The alumni really took a leap of faith in giving it to us,” said Jean Whelan, assistant director of the Barbara Bates Center for the Study of the History of Nursing at the University of Pennsylvania.

“At the time everyone here was white–in the Bates Center–and this African American group came and trusted us to take care of their collection and do it well,” she said.

Playing a key role in Pa. health care integration

Many Mercy-Douglass nurses helped integrate health care in Pennsylvania, and Whelan and her team are studying that change and trying to better understand the role of Mercy-Douglass alums in the health care landscape.

When Philadelphia hospitals first began to desegregate; those first steps were slow and halting, Whelan said.

“They would say to them ‘you are going to be the first African American nurse; are you willing to do that?’ The white nurses might have refused to work with them, there would be all sorts of negotiations about what bathrooms they would use. Would they put their coats in the white nurses’ locker rooms? Whether they could order the nurses aides–the people under them—around,” Whelan said.

“They would have to think long and hard about whether they wanted to go through what might be a very unpleasant experience.”

A difference in opportunities

Mercy-Douglass nurses began their careers years before federal law began to force change in health care.

Elizabeth Keys Williams, 82, was still in high school when she first noticed the differencs in opportunities available to her.

Williams—whose maiden name is Keys—and a white friend both wanted to be nurses.

“Her name was Marilyn,” Williams said. “The counselor who was advising our class had given her all kinds of information and different hospitals to apply to. She said, ‘Libby go. Go to Mr. So and So. Go to him, he will help you.’ I went to him. He said I wouldn’t know where to tell you to go.”

The 17-year-old tried to enroll at a Harrisburg nursing school anyway.

“I asked ’em for an application. ‘No.’ They let me know they didn’t have any black students,” Williams said.

Williams eventually made her way to Philadelphia and entered the class of 1954 at Mercy Douglass.

There, they learned to do things “the right way.” “Say, for example, you had to catheterize a woman—it was a sterile procedure–if you made one mistake, everything was stopped and you had to start all over again.”

The students also made sure they looked the part of a proper nurse. Every nursing school had its own signature nursing cap.

Other nurse caps had complicated pleats, or a bit of fluff or frill that had to be starched and ironed, but Williams said the Mercy-Douglass cap was sophisticated and no-nonsense—”just like the students.”

“Can you just imagine a white dress and your white shoes and your cap,” Williams remembered. “And here you come with your cape, it’s just flying in the wind. You felt like, oh: ‘I’ve really got it made.’ Everyone was just so proud.

The Mercy-Douglass cape was Navy with a red lining. The buttons were gold and the initials M.D.H. were embroidered with gold thread on the Mandarin collar.

Establishing a career amid discrimination

After earning her diploma, Williams left Philadelphia to work in psychiatric care. She was the first black nurse to work at Harrisburg State Hospital.

Her colleagues often showed her kindness, Williams says, but the hospital policies weren’t so fair. In the 1950s, the convention at many hospitals was that a black nurse wasn’t allowed to supervise a white nurse, no matter who had the most training or seniority.

“If you were in meetings about certain really problem patients, and I might have had the best knowledge about that, that physician is going to ask the white nurse before he talks to me,” Williams said. “The doctors–some of them, not all of them–would not recognize you. If they didn’t have to talk to you they wouldn’t.”

Even harder—maybe–was the treatment she received from aides and assistants.

“It was not only some of the whites who were discriminatory against you, it was many of the blacks,” Williams said. “They did not give me the same respect they would give the white nurse; it was disheartening.”

Delores Brewer had similar experiences when she left Mercy-Douglass to start her career.

“My first job was at Philadelphia General Hospital. I only lasted three months,” Brewer said. “They had very few black nurses at that time and the nurses that were in charge, they didn’t want to accept the fact that you were on the same level and you had the experience that many of them didn’t have. They would try to break you.”

Times changed, but those slights continued for years. Williams says her uniform wasn’t much of a cloak.

“I definitely remember this gentleman coming in and he walked up to me, and he said, ‘I’d like to speak to the nurse.’ And I said: ‘You’re speaking to the nurse.’ He said, ‘No, I want to speak to the nurse.’

“I’m standing there–white cap, uniform–and it had a pin on it that said: E. Williams R.N. Didn’t make a difference. He did not talk to me. He walked away. His loss,” said Williams.

In 1964 the Civil Rights Act began to force fair practices in the workplace. A year later the Medicare and Medicaid program pushed hospitals to accept black patients–or forgo funding from the federal government.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.