Not your father’s Band-Aid: The quest for smarter bandages

Listen

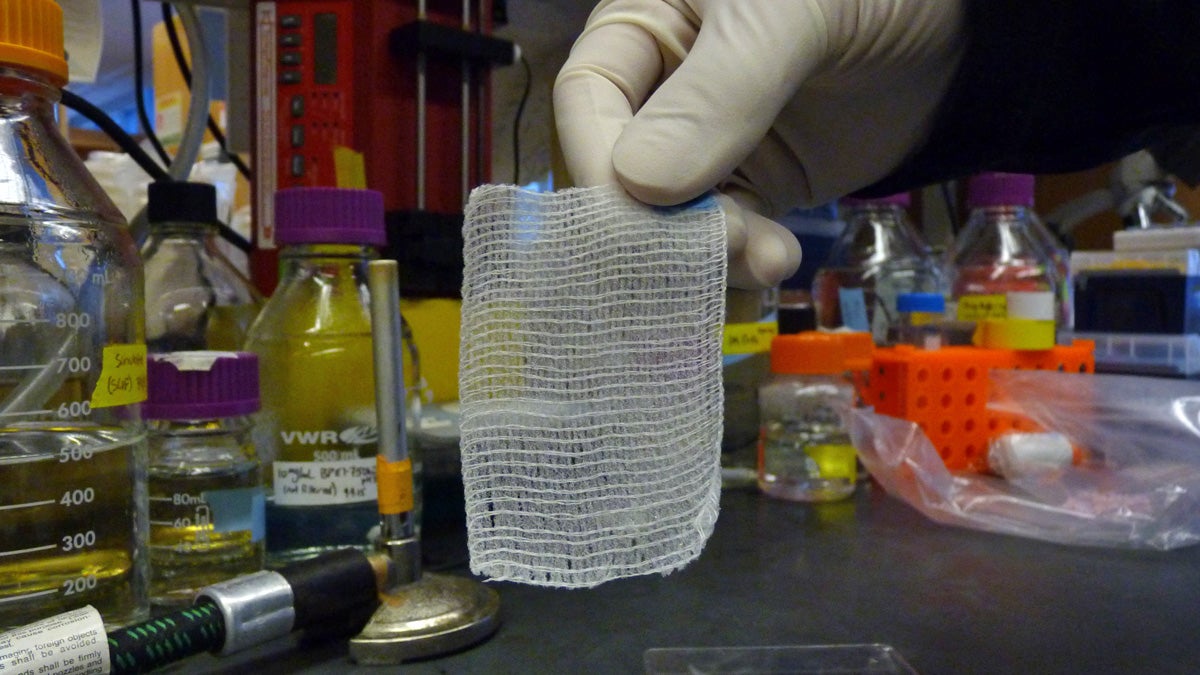

This piece of gauze is part of an on-going mission for smarter bandages. (Todd Bookman/WHYY)

Nanotechnology is producing an all-in-one first aid kit.

For the past 95 years, Band-Aids have been the go-to treatment for paper cuts, scrapes and skinned knees. Over 100 billion of them have been stuck on small injuries, warding off infection and reducing healing time.

But bigger and more complicated wounds, like those suffered by soldiers, need a better solution. That’s led researchers in high-tech laboratories around the globe on the quest for smarter bandages.

At Harvard Medical School, post-doctoral fellow Bryan Hsu has spent time looking into ways to embed a range of drugs directly into gauze, engineering it so they release at predetermined dosages.

“So the treated bandage looks just like a regular cotton gauze,” he says, holding up a few inches of the white, transparent prototype material.

“It is fairly flexible, a little bit stiffer because it has this thin polymer coating on it. But very lightweight, and very stable.”

The polymer coating is made up of layers of nanofibers, which get sprayed onto the gauze using an ultra-fine mist. They contain a special series of amino acids, one of the building blocks of the human body.

“Nanofibers are based off of something that is observed in nature. They are synthetically made, but completely biodegradable, and non-toxic,” he says.

Bryan Hsu, a post-doctoral student at Harvard Medical School, in the lab. (Todd Bookman/WHYY)

The nanofibers, which were developed at MIT by Dr. Shuguang Zhang, remain on the gauze until coming into contact with a wound. The presence of liquid–in this case, blood–causes them to release. The fibers then act as a coagulant, speeding up the clotting process.

And all of this happens on a nanoscale. Each individual nanofiber is 10,000 times thinner than a strand of human hair. To give a better sense of what’s happening, Hsu pulls up images on his computer screen.

“You can see they look like spaghetti that’s entangled. Entangled spaghetti,” he says with a smile.

The strands of nanofibers snarl the flowing blood cells, which look like meatballs, slowing blood loss.

In animal testing, the nanofiber-coated gauze stopped blood flow from a wound in two minutes, compared to five minutes for traditional gauze.

Hsu and colleagues are working on bandages that, along with the coagulant, can also seep out an antibacterial drug, such as vancomycin, plus a painkiller. That type of all-in-one bandage could stabilize soldiers who endure a bullet or shrapnel injury until they reach a hospital.

One problem says Hsu, who used to work at MIT’s Hammond Lab, is getting the various medicines to release at the correct rate.

“Each type of drug is different, their chemical structure is different, their properties are different, and their stability is different,” he says. “So making something that can release a drug with the release profile, or the timing that you want, can be challenging.”

Other laboratories are taking smart bandages in different directions. At UC Berkeley, researchers are using sensors to detect bed sores before they break through the skin’s surface. Another early-stage device monitors oxygen and temperature inside a wound, alerting doctors to potential infection.

“A lot of people are trying to do similar things, all looking at it with different strategies,” says Hsu. “Some are really, really good compared to the rest, but that is from a research and academic perspective.”

From an industrial perspective, cost, manufacturing ease and availability of patents could determine what products make it to market.

Add to that the complex regulatory process surrounding these types of devices, and it could be years before anything reaches store shelves.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.