More deadly than HIV: Hepatitis C, a silent killer

Listen

Navin Vij found out that he had Hepatitis C after living with it for 26 years. (Paige Pfleger/WHYY)

Navin Vij was delivered by C-section on June 22, 1983. At 27 weeks, he was a micro-preemie, staying in the intensive care unit for a couple months. Eventually, he was released and grew into a healthy kid.

Throughout his childhood, his mom would repeat a phrase to him, sometimes in Hindi but always with a warm smile, that stayed with him — everything happens for a reason. And the challenge in good and bad is to figure out why.

Fast forward to 2009, Vij is 26 years old, and on track to becoming a doctor.

During his first year, he was doing a blood draw in the intensive care unit, and accidentally got stuck by a needle.

Health providers dread this because it can be serious. But Vij didn’t think much of it. Still, he stopped by employee health services and had his blood and the patient’s blood checked. Then he went back to his daily routine.

A few days later, health services contacted him. It was a phone call that totally changed his life.

“They told me I had Hepatitis C,” Navin says. “I just remember my world stopping. I remember the air being sucked out of the room. I remember just standing in this hallway at work sort of feeling dumbfounded, feeling like I was having a moment of deja vu that would never go away.”

At the time, what Navin knew of Hepatitis C was this — it was one of the causes of liver disease, it was the leading cause of liver transplants in the United States. More worrisome, though, was that Vij had seen people in the intensive care unit who were dying from complications from Hep C, cirrhosis and liver damage.

“I had seen people in that situation, and I put myself in that bed,” Vij says. “And it scared me.”

The first phone call he made was to his mom. She told him not to worry, that they would figure it out and everything would be okay.

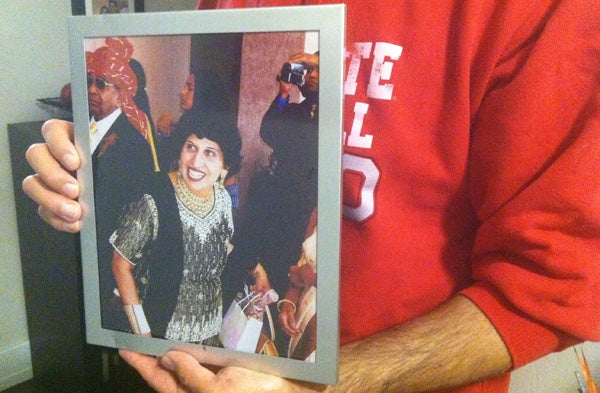

Navin holds a photo of his mother. (Elana Gordon/WHYY)

“And after getting off the phone with my mom, that phrase came back to me: ‘Everything happens for a reason. The challenge in good and bad is to figure out why,'” Vij says.

In search for the why, Vij set out on a mission to understand how he even got the disease. Hep C is spread through blood to blood contact, often through sharing needles. But it turns out, the patient from the blood draw didn’t have Hep C.

So Vij started delving deeper into his past. Which was when he realized that in 1983, when he was born, the nation’s blood supply wasn’t being screened for Hepatitis C. Which is when he made a realization — he had been living with Hep C for about 26 years.

Hep C is sneaky. It’s not like a cold where you immediately recognize it through symptoms like a cough or soar throat. It often remains silent for decades, until it’s already damaged the liver. An estimated 3 million people in the U.S. have it, and the number of associated deaths have surpassed that of HIV infections. But most people don’t even know they have it.

When Vij found out he did, he wanted to keep quiet about it. He didn’t feel comfortable talking about it.

He told his girlfriend, now wife, Abbey, who’s a nurse. They were surprised how even in their well-educated medical circle there was misinformation and stigma.

“I remember she came home one day and she talked about how she was taking care of a patient who had Hepatitis C in the intensive care unit,” Vij says. Abbie had touched the bedrail without gloves on, and one of her superiors scolded her for it, saying that Hep C was that infectious.

“I thought at the time, ‘I’ve been a lot closer to it than this!'” she says.

Hepatitis C has no vaccine, and only a small portion of those infected naturally clear the virus. The main option has long been a drug combination that includes regular injecions for six months. Vij started treatment, but stayed in residency. It was tough, he says.

He was dehydrated. He had chronic flu symptons. He was depressed. And these treatments available at the time weren’t even guaranteed to work. There was a 20 to 40 percent chance that they wouldn’t. But, during this time when he started treatment, something else happened — his mom was going through her own treatment. She had developed head and neck cancer and was having a recurrence. She fell into a coma and died a few months later. And shortly after that, he found out that his treatment had worked. He was cured of Hep C.

“It was just a bittersweet moment,” Vij says.

He thinks about how she would have reacted, what she would have said. No doubt, she’d have that smile, he says.

“She’d be like, ‘Look, see? You got through this, it’s not the end of this, this happened for a reason, this has changed your life, but the point is not just how it changed your life but what will you do with it to help change the lives of other people?'”

Today, Navin has been working to amplify the voices of what’s long been a silent disease, through advocacy with the group Caring Ambassadors and through research as a Robert Wood Johnson Clinical Scholar in Philadelphia. But he’s troubled that as much as treatment has dramatically improved since he went through it, that won’t mean anything if people aren’t screened, if the disease remains a secret even to those who have it.

“I was lucky to get that needle stick and find out my diagnoses,” he says. “I was lucky to have support to get through treatment, and I was lucky to be cured. And when I went back to medicine, when I thought about patients I was taking care of, when I thought about Hepatitis C, I want other people to feel lucky.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.