Lots of disagreement remains about when to start mammography

Listen

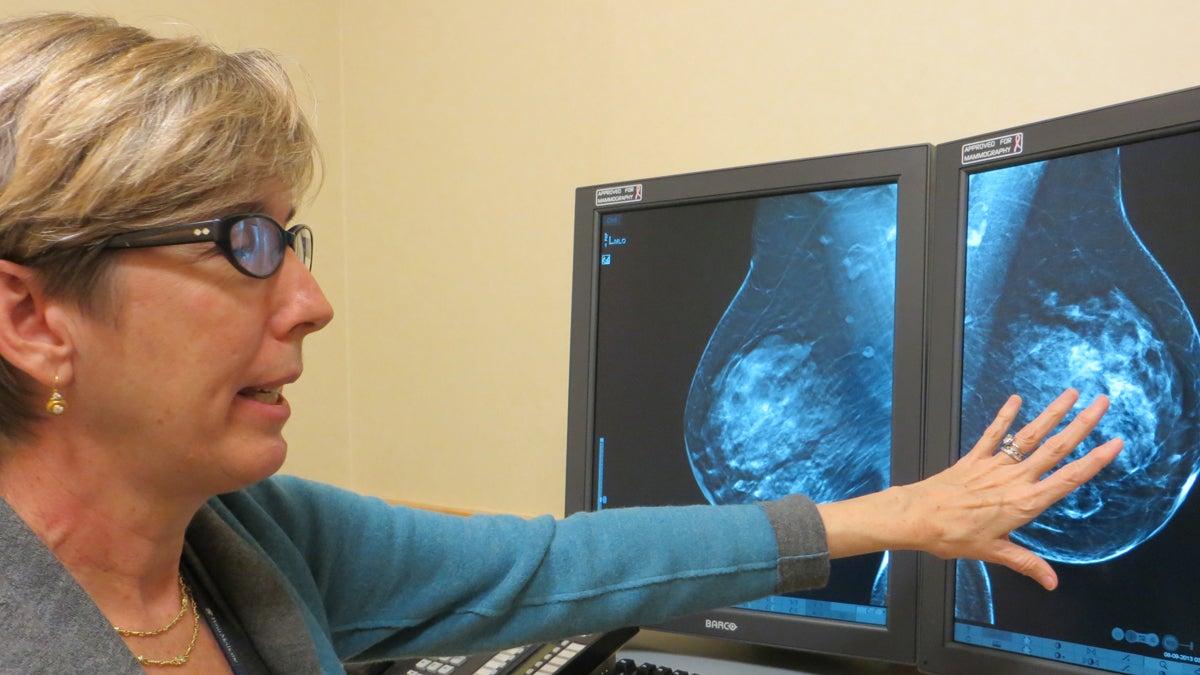

Radiologist Emily Conant

Four years after an uproar over revamped mammography guidelines, women’s breast screening choices remain complex.

Back in 2009, when an independent ― but federally funded ― panel of medical experts issued new recommendations on mammography screening, the change set off a kerfuffle in the medical community. In the media ― a firestorm.

Then what happened? Four years later, what are women doing? What advice is actually sticking?

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force advice to most women was to push back the start-date for regular mammograms from age 40 to age 50, and the prevention experts recommended follow-up scans every two years, rather than every year.

Radiologist Emily Conant, head of breast imaging at Penn Medicine, says the taskforce did a poor job communicating the pros and cons of the screening test in 2009, resulting in mass confusion.

“The flip flopping …” Conant said. “‘Get a mammogram, don’t get a mammogram.’ We looked silly. It’s such a mixed message, it’s all about how you slice and dice the data.”

Many medical groups disagreed — loudly ― with the taskforce guidelines. The American Cancer Society, for instance, maintained its advice that women with average risk should have annual mammograms starting at age 40.

Addressing the harms

Mammography — like any medical procedure ― can have downsides. Prevention experts on the taskforce said their recommendation acknowledges that for younger women especially, the benefits of mammography may be smaller ― and the potential harms greater.

“I think the recommendations really emphasized the harms of screening,” Conant said. “Too many additional images, too many callbacks for screening and biopsies.”

“Certainly we don’t want to do unnecessary biopsies — those are psychologically traumatic, physically traumatic — no one wants a needle in their breast,” Conant said. “But all of those are sort of put in the same bucket. Most of us feel that’s not appropriate; there are different levels of harms.”

The taskforce advice to women under age 50 was to make an individual decision about when to start getting mammograms after having a conversation with a doctor or nurse. That’s nuanced advice, but Conant says many women only saw the stark headlines.

“Someone tells you … top of the fold of the New York Times: ‘Maybe don’t get it.’ It’s like yeah … I’m not going to go,” Conant said.

It can take years for a new recommendation to trickle down to doctors and patients.

What impact did the guidelines have?

Since 2009, national data show very little change in the number of women getting mammograms. But across the Philadelphia region ― at PennMedcine and Fox Chase Cancer Center ― radiologists have noticed a decline in the years after the prevention panel released its advice.

“It corresponded with the economic downturn, so it’s hard to know just how much of a role those guidelines actually played,” said Kathryn Evers, chief of breast imaging at Fox Chase Cancer Center.

She says mammography is the best tool we have for the vast majority of women.

“I have my mammogram every year, so I obviously believe in it. I think it would kind of be hard for me to do my job if I didn’t,” said Evers, who is a radiologist.

Still, Evers says these days — post 2009 ― no one’s selling mammography as a perfect tool.

“I think if we hyped it a little bit less, maybe we’d look at the facts a little bit more.”

Health researcher and physician Steven Woloshin says the 2009 fallout over mammography guidelines has helped change the tenor of the debate about all cancer screening.

In the past, advocacy, patient groups and public health officials often used a “harder sell.”

“For example, there was a famous advertisement from the American Cancer Society, which said … if you are a woman and haven’t had your mammogram, you need more than your breast examined ― implying that you were crazy,” said Woloshin, with Dartmouth’s Institute of Health Policy and Clinical Practice.

Woloshin helps patients, policy makers and journalists understand the uncertainties of different medical interventions. He says, today, if a woman opts to get her mammogram less often, she’s less likely to hear that she’s ‘bad’ or ‘irresponsible.’

“Those ideas have softened a little, and I think there’s more room for debate, a little more room for skepticism,” Woloshin said. “People are a little more open to the idea that screening can have benefits and it also can have harms.”

For mammography, those harms include “over diagnosis.” Among doctors, that term means finding a cancer that may never grow large ― or spread enough ― to cause true problems.

“And in fact if the person hadn’t been screened, and the abnormality had never been discovered, the person would have lived their entire life without knowing about it and would have died from something else,” Woloshin said.

Right now, medicine’s not very good at distinguishing less aggressive tumors — from the “really uglies,” said radiologist Emily Conant.

Yet, breast screening is getting better, Conant says, and that’s another change since 2009.

Today, every woman who goes to Penn Medicine for screening gets digital breast tomosynthesis — or a 3D mammogram. A traditional mammogram is an x-ray of the breast. Three-dimensional mammography uses a technology similar to CT scans, or computed tomography.

3D mammography comes with its own set of risks and benefits to consider, but Conant says using an older technology to check complex, dense breast tissue can be like that game Where’s Waldo? By contrast, she said 3D scans from state-of-the-art mammography are especially good at finding invasive tumors.

“They’re the killer type cancers that can get out into the breast, lymph nodes and really cause havoc,” Conant said.

Back in 2009, 3D mammography was still very new. Conant says the U.S. Preventive Services Taskforce largely did not consider 3D technology in its evaluation of how well mammography works.

“I think they used the wrong data,” Conant said. “I think they can do better.”

Four years later, the taskforce is taking another look. A new review of the evidence is underway this year.

In the meantime, here’s a recap. While the prevention taskforce suggests most women — with average breast cancer risk ― begin routine mammograms at age 50, many medical groups say: Start at 40.

For younger women — especially — nearly everyone says before you make a decision sit down with a professional and talk about your personal health history, values and family risk.

A final note — on what’s changed, and what hasn’t: Under the Affordable Care Act, most insurance plans and Medicare must cover annual mammograms for women beginning at age 40.

Laura Benshoff contributed to this report.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.