Lightning storms, oil rig interference and other research challenges below the Gulf of Mexico

Listen

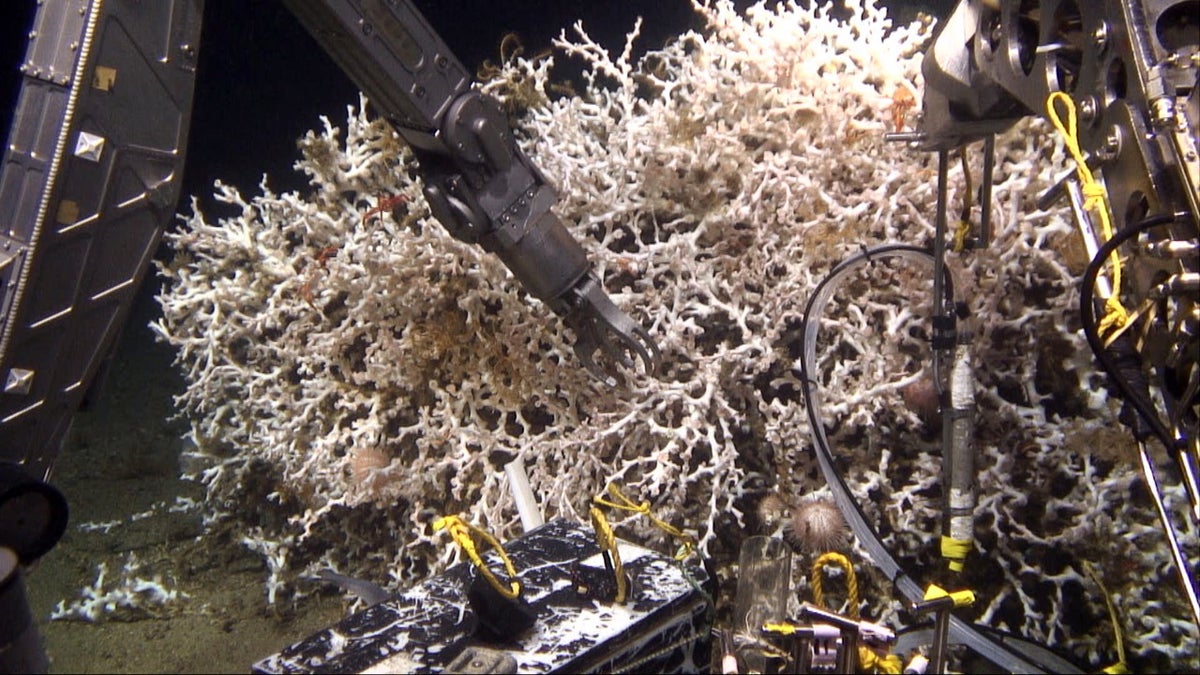

Samples of deep sea corals are taken by Temple researchers below the Gulf of Mexico. (Photo courtesy of Ivan Hurzeler

We check back in with Temple University’s Erik Cordes after a three-week, ocean acidification research trip.

A few weeks ago, Pulse host Maiken Scott spoke with Dr. Erik Cordes, associate professor of biology at Temple University, while he was aboard the submersible Alvin in the Gulf of Mexico. He was with a team of researchers collecting coral samples to study the effects of ocean acidification on the deep sea.

The team returned on May 17 with an abundance of samples to study in the lab. They’ll now look at the genetics of these deep sea corals over the next few weeks to see if they have genes or different mechanisms that allow them to survive under the adverse conditions of ocean acidification.

Cordes says the trip was largely a success, but the team ran into their fair share of complications along the way.

The first being weather related issues, which resulted in what Cordes recalls as one of the most amazing thunderstorms he’s ever seen.

“We were trying to recover an autonomous vehicle that we were using and it has a strobe light at the top,” said Cordes. “This was pre-dawn, about five in the morning and it was difficult to see the strobe light. Lightning was so frequent that we couldn’t tell the flashing light of the AUV from the flashing lights in the sky. It was really incredible.”

One other minor challenge was getting acquainted with the newly rebuilt submersible, Alvin.

But perhaps the most frustrating obstacle for the crew was what they noticed on day one of the trip.

“We pulled up to the largest coral reef in the Northern Gulf of Mexico and there was a brand new drilling ship less than a mile from the reef, sitting right where we wanted to go,” said Cordes.

The researchers were told they couldn’t get within a mile of the drilling ship.

“So they can get within 2,000 feet of the edge of my coral reef but my ship can’t get within a mile of them, which effectively puts a few thousand feet of coral reef off-limits to research, because they are drilling for oil right next to this reef,” Cordes said.

This wasn’t the only drilling ship the team encountered on the trip. Cordes says there were a few others in the areas they were planning to research.

“I was really astounded,” he said. “This was the most energy company activity I’ve ever seen out there. It seems to have really increased.”

Despite the few hiccups along the way, the the team was able to gather plenty of samples from the deep sea to continue monitoring ocean acidification.

“We collected a lot of corals and transported them alive back to the lab at Temple University and we’ll be going through some experiments over the next weeks and months to determine their threshold for survival under these ocean acidification scenarios,” said Cordes.

We’ll check back in with Cordes once his team’s ocean acidification research is complete.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.