Lessons from Vancouver: U.S. cities consider supervised injection facilities

Vancouver is home to North America’s first, public supervised injection facility — and an explosion of spin-offs designed to prevent overdose deaths.

Listen 35:14

Inside Insite, North America’s first public supervised injection facility, located in Vancouver. (Elana Gordon/WHYY)

In 2016, opioid related deaths surpassed 40,000 in the United States, more than double the toll from six years prior. Deaths continue to climb.

Yet an opioid overdose does not have to be fatal.

When such drugs overwhelm the brain’s receptors — slowing down and stopping vital functions like breathing — that can all be reversed if someone is there to respond. It’s why the United States’ chief medical doctor recently urged more and more Americans to carry the overdose reversing medication, naloxone. If administered soon enough, naloxone removes a drug’s fatal grip and can bring someone back to life.

But people who use illegal drugs often use in hiding, in unsafe situations — and alone.

If a bad hit happens in a dark alley, an abandoned building, a solitary room, or the woodsy brush out of view of others, help may arrive too late.

The stark reality has prompted desperate cities from San Francisco to Philadelphia, from New York to Seattle, to consider something that’s never been sanctioned in the United States — opening a supervised injection facility.

Supervised injection facilities are places where people can bring in illicit drugs and inject them without fear of harassment and under medical supervision, in case of an overdose. Proponents say such spaces help people use in safer ways. And, they argue that those sites are often connected to recovery services where drug users can get help when they are ready.

In public health, this type of approach falls under the umbrella of harm reduction.

It’s a philosophy that shifts the emphasis from stopping drug use completely to lessening the harms of drug use — anything from using clean needles to prevent HIV or caring for an abscess before the infection worsens.

But around the world, more than 100 facilities are in operation, primarily in Europe. But supervised injection is a contentious idea in the United States.

Recent proposals have fueled confusion, fear and pushback. Injection sites are technically illegal under federal drug laws, with government leaders in states like Pennsylvania reluctant to back the idea. Tensions have boiled over at community meetings like one in Philadelphia in April.

“I feel like we’re telling people to just stay on drugs, keep ruining your life!” said Joelle Anderson, who is in recovery.

“We don’t need one of these sites in my neighborhood,” said resident Gilberto Gonzalez to a resounding applause. He worries a facility would adversely affect the area and the safety of his son, especially going to and from school.

“They also need to protect the community. They need to protect my son.”

Looking to Vancouver

Vancouver is home to North America’s oldest injection site. In the thick of that city’s big drug scene is Insite, the continent’s first sanctioned site open to the public.

Several years and millions of supervised injections later, Insite has become inundated with questions and visits from curious U.S. city leaders now mulling a similar approach.

“San Francisco has been up here en mass,” said Darwin Fisher, Insite’s program coordinator. “New York sent up some representatives from the police department, the mayor of Ithaca came up.”

Philadelphia officials passed through last November.

Chinazo Cunningham, chief of general medicine at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, visited in May.

“We need to be open to all potential options,” said Cunningham, who is involved in evaluating New York City’s plan to open four sites later this year.

Inside Insite

Insite is located in the center of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside, home to a decades-old outdoor drug market. The neighborhood also contains lots of homelessness, social services, and many single-room occupancy hotels.

The main avenue is wide but can be hard to walk through in certain parts that are thick with people, people’s things, and things people are selling … everything from DVDs to golf clubs, to the shirts off people’s backs.

Vancouver is a port city with mild winters, so this street activity is just a stone’s throw from the water and a beautiful mountain view. Cranes and new condominiums tower from above.

“It’s funny, the poorest postal code in Canada — the moniker the Downtown Eastside often takes — literally overlaps the most expensive neighborhood in Vancouver,” said Travis Lupick, a local journalist who wrote a book about the history of supervised injection in Vancouver. “This neighborhood, it’s being crunched into a tighter and tighter space.”

The neighborhood’s main businesses shuttered decades ago, making way for poverty and pain of all kinds.

“I myself, I was clean for 10 years, and then I buried my dad and I just kind of fell down from there. I’ve just been down here ever since.” said Benji, who only shared his first name, because of his concern about illicit drug use.

He’s a regular at Insite.

“I think they’re great, there’d be a lot more people dead without them,” he said.

Insite is a dark green building that can be easy to miss, with its name printed in white on the window. No big sign.

Before opening at 9 a.m. one morning this spring, two people who run the place huddle over a man slumped against the building.

The two check his hands, his pulse, and ask questions. The man is able to respond.

“So we checked that fella for an overdose event, just cause his posture was concerning,” said Tim Gauthier, Insite’s clinic coordinator.

Unprompted, the man asked him about detox.

“That’s very typical, that’s usually how those things play out,” Gauthier said.

Short term beds and longer term recovery services are located right upstairs in an affiliated center called Onsite. That’s part of the crux of this place, he says, having treatment and health care readily available.

Darwin Fisher, Insite’s program coordinator, says the other key to the place is being right in the thick of where people are using drugs.

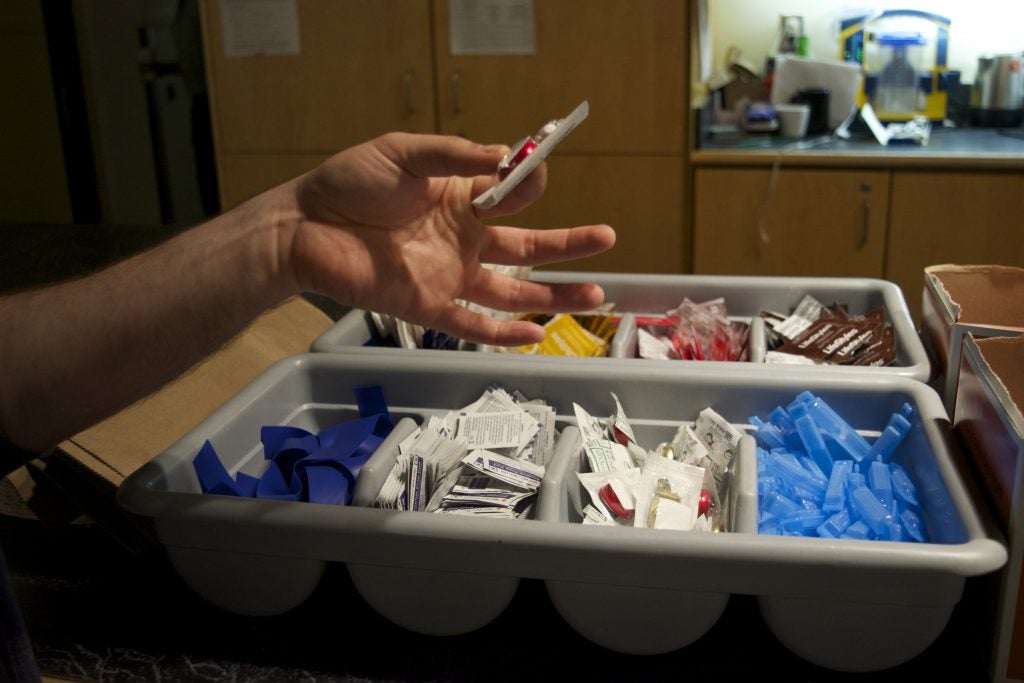

“After about two, three million visits it’s mildly shopworn but not by any means grody,” Fisher said, walking around the front waiting room area. It’s an open space with a few chairs, a counter, harm reduction supplies, and a sink. Next to it is a sign encouraging people to drink water.

“Accessing things as basic as running water is really important part of this,” Fisher said.

How Insite works

The region’s main health agency, Vancouver Coastal Health, oversees Insite in partnership with a local housing non profit, the Portland Hotel Society. People may come in multiple times a day to inject drugs.

In addition to a safe, clean place to get high, users come to avoid getting sick from withdrawal.

People share a small amount of information when they sign in, like what kind of drug they’re using. They can even get their drugs tested to confirm what’s in it.

People also give a code name — Peaches, Mischief, or Misfit, for example.

That anonymity and minimal paperwork is all by design, says Fisher. The less bureaucratic the better. The point is to make people comfortable, so they want to come inside. That way everyone can focus on developing relationships.

“That’s part of what this place and space is about,” he said. “It’s not just about keeping people alive — that’s the primary goal — it’s about making a space where drug users are allowed to feel like people.”

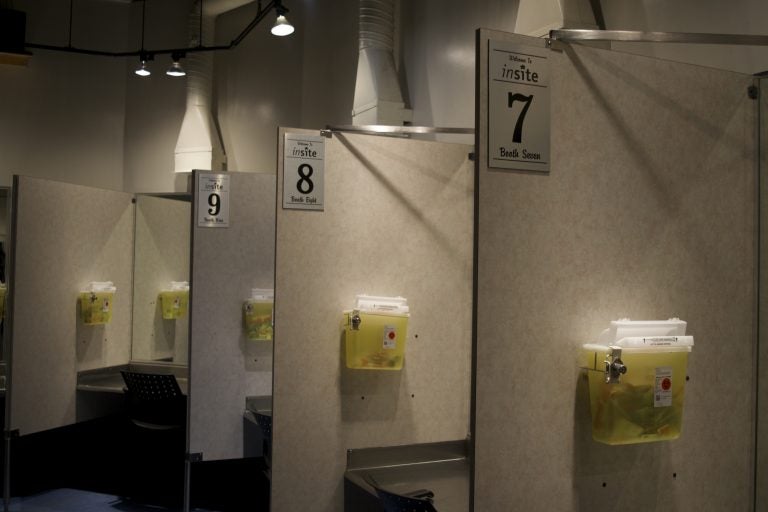

Beyond the front waiting area is the main room, the inner sanctum for supervised injection. It’s a big space, resembling a hair salon, with 13 cubbies against the wall. People get called back one by one as booths open up.

“It’s kind of a mirrored cubicle with high walls and spotlighting over top of each booth,” Gauthier said, walking around the room before it opens. “The rest of the room is fairly dim lit, except the staff stations.”

There’s no time limit for the booths.

“People may need time to use safely for various reasons,” Fisher said. “We’re also mindful that this is a respite from the street and at times it might be difficult for people to leave the only situation that feels vaguely safe for them in a day.”

In the middle is a long table where people can get clean injection supplies like sterile water and needles.

Next to the main injection space is a private room for health visits and wound care. Next to that is the “chill out lounge,” an open area where people can go after they inject. There’s couches, tables, coffee and juice. Peers — people who use drugs themselves — work there. Other staff and counselors are on hand too. Fisher says this is often where conversations about the other needs — housing, mental health — come up.

Once Insite opens, music playing out of speakers and a low hum of conversation fills the room. People settle into individual booths, unpacking the drugs they’ve brought, doing their thing, prepping and injecting them.

It’s a ritual that happens hundreds of times a day at Insite. Injection can take 5 minutes or as long as 25 minutes.

Staffers help.

“When somebody’s struggling with their injection, like we can see they’re getting frustrated, agitated, poking or stabbing away at themselves, it’s our responsibility to see if we can help make that safer for them, to find a safer vein,” said Gauthier, who’s a nurse.

Staff won’t poke anyone’s skin or push drugs in, but they will suggest better spots and offer injection advice to reduce infection risks. Other staffers, meanwhile, stand back to keep an eye on what’s going on. Like lifeguards, they’re looking out for anyone who might be in trouble.

“It’s like an out of body experience,” recalled Rhea Jane, a regular at Insite who says she has overdosed inside.

“There were times in my past where I did want to overdose but I certainly didn’t go to Insite to do it. If you want to die you don’t go where no one’s died,” said Daniel Beaverstock.

Gauthier says unless someone is experiencing other health problems, he rarely has to call for paramedics.

“No one’s ever died here or in any other supervised consumption site worldwide,” he said.

When a drug user overdoses, staffers offer a quick, choreographed response.

He and others are well versed in responding to people who become unresponsive.

“We go over to booth right away try to stimulate them with voice first,” Gauthier said.

“And then before touching anybody, which is respective to people’s trauma history — we don’t want to touch without getting consent first — so we’ll try to bang on a table or chair.”

From there, the responder applies firm pressure to the shoulders, and then gently tips someone back on the floor. Rescue breaths are next. Someone brings out the oxygen tank and naloxone.

The goal, Gauthier says, is to be as gentle as possible.

“We want the person to stay with people who care about them and are going to watch them,” he said. “We respond with kindness.”

The research

When the Canadian government approved the opening of Insite as a pilot, exempting it from federal drug laws, it mandated rigorous evaluation.

At that time, researchers at the B.C. Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS had already been following hundreds of active drug users in Vancouver.

That experience meant researchers had a baseline group to study, once Insite opened.

When the Canadian government approved the opening of Insite as a pilot, that move exempted the program from federal drug laws. Canada also mandated rigorous evaluation.

Researchers had an advantage going in: they had already been following hundreds of active drug users in Vancouver. That gave them a baseline group to study once Insite opened. They also relied on information from the coroner’s office and government health care databases.

M-J Milloy with the British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, says the benefits of supervised injection in Vancouver became clear to him and others leading the evaluations.

They found a decline in rates of fatal overdoses around the facility and dozens of deaths averted annually. People were less likely to share needles, Milloy says. And drug users were more likely to enter a detox program and enroll in longer term recovery services.

“That might seem odd to people. You know, you give someone a safer, cleaner, warmer drier place to inject and they end up going into addiction treatment,” Milloy said. “I think what this shows is that what Insite provides for people who are using drugs is — for many people for the first time in their drug using careers — a place which is an official healthcare setting which is not judgmental, which does not stigmatize them for their drug use, and which accepts that they are people first and foremost.”

Based on drug trends and interviews with people using Insite, Milloy found no signs of a so called “honey pot effect” after Insite opened, meaning it didn’t increase or encourage drug use.

“It’s a place where they can access healthcare, and where their exposure to an increasingly toxic drug supply can be managed and mitigated in an effective sense,” he said.

After 15 years, Insite has gained widespread support in the region. But as Darwin Fisher, Insite’s program coordinator recalls, says it was not an easy sell.

“It was a struggle to get this place set up,” he said. “It was the struggle of years and lives to get this going.”

Years of drug user activism

Insite was designed and pushed into reality by the people who’ve used the space.

“Vancouver’s embrace of harm reduction was entirely led by activists and by this community, the Downtown Eastside,” said journalist Travis Lupick. “It was an entire decade of concerted efforts and activism that really brought the government kicking and screaming at the end.”

That story begins back in the 1990s. Vancouver was in the midst of an overdose and HIV crisis.

“We had people in the community center, around the community center, overdosing in bathrooms and all over the neighborhood. Ambulances were appearing,” said Donald MacPherson, who at the time was working at Downtown Eastside’s main community center.

Overdose deaths shot up from a couple dozen to more than 350 a year in the province, partly from a more potent supply of heroin.

“And we were doing memorial services in the community center every two weeks, you know, cause this community had been so hard hit,” MacPherson said.

Ann Livingston, who has lived in the neighborhood for decades, remembers the neglect, the trauma, the loss.

“It was like a sinking ship, people were terrified,” she said.

Users held vigils and rallies.

“These guys would get up there and go, ‘my friends are dying!’”

Livingston was one of the major forces behind organizing a drug user union. They first met in a nearby park, then landed their own space, where they even ran an illegal injection site that police would often close down.

As deaths continued, pain turned to passion.

“If you’re part of something that’s progressing, people aren’t so depressed,” she said. “If it’s constant deaths and no matter what you do and you’re powerless. That’s when you get really intense trauma.”

People like Bryan Alleyne, who was an active drug user, started taking the lead.

“Well in the beginning we had to do a lot of marching,” Alleyne said. “We had to go to many, many meetings.”

Alleyne has been working at Insite as a peer since it opened 15 years ago.

Before that he’d become active in the drug users union. Union members took over city hall meetings, demanding more attention and support, for basics including medical care.

He and other drug users would tell their stories to anyone and everyone who’d listen: city officials, police, neighborhood groups, and addiction specialists. They wanted an alternative to shooting up in alleys, with dirty water and used needles. They also wanted a space where they could safely inject, free from harassment.

Leaders of a non-profit housing group called The Portland Hotel Society, where many people who used drugs lived, also headed that push, and the campaign to educate surrounding communities.

“Chinatown didn’t want this, Gastown this didn’t want this, Strathcoma didn’t want this,” said Alleyne. “And these are all areas next to us, right here, right there.”

Albert Fok remembers the intense pushback.

“The overall concern is the neighborhood being the way it is, is [a supervised injection site would] be attracting undesirable people, attracting undesirable activities, and bringing down a plethora of social issues,” he said.

For more than two decades, Fok’s family has run a traditional herbal medicine shop. He became a leader in Chinatown business associations. Fok says in this community in particular, many people view drugs as a criminal act. Sanctioning use, whatever the public health implication, was unacceptable.

While drug users lobbied for a place of their own, opponents organized protests, too.

Meanwhile, police were extremely wary.

“I thought that supervised consumption sites would act like a magnet to draw people in, almost like a tourist destination,” said Bill Spearn, a longtime member of the Vancouver police department. “Where they would come to Vancouver to specifically use drugs.”

This concern, often referred to as the honey pot effect, turned out not to be true. Interviews and surveys with people at Insite about their history of drug use showed no signs of the honey pot effect. The place wasn’t encouraging use or drawing more people in to the neighborhood than would otherwise be there.

By the early 2000s, Donald MacPherson, from the community center, had moved into a position at city hall. He was tasked with drafting drug and addiction policies for the mayor. He and others worked from the inside to convince leaders to try the approach.

“I just paraded experts in front of the mayor,” MacPherson said. “The mayor, he was a very blue pinstriped-wearing right of center, Mayor Philip Owen.”

They mayor would listen, and spend time in the Downtown Eastside, listening to people affected by the drug crisis.

“He became interested and started to advocate for change, cause he didn’t know what to do,” said MacPherson.

The opening of a supervised injection site became a defining political issue. MacPherson says it wasn’t just a Downtown Eastside problem anymore. Families from all over were suffering from the loss of loved ones. Mothers from other neighborhoods got involved.

Pressure mounted. Activists with the Portland Hotel Society even built a supervised injection site, modeled off a hair salon, on East Hastings street and challenged the city to run it.

In 2003,Vancouver moved forward and opened Insite as a pilot with federal health funding.

Fok, the nearby business leader, says what came after Insite opened was hard to ignore.

“There is clearly a reduction of people shooting up in the back alleys. That’s not to say there isn’t any now, there will always be a few but, but the number has dropped substantially. We don’t see as many discarded syringes as they used to be,” he said.

“This is a welcoming sight. You don’t see people hiding behind your car in a back alley shooting up.”

Spearn, now an inspector with the police force, recalled that outdoor disturbances seemed to go down. Before Insite, in the 90s, he’d spend entire days going from overdose to overdose. It wore on him. Then, that changed.

“I started putting this puzzle together and, you know, I think you mellow as you get older, too. And you’re able to look at things easier,” he said. “And it was just, it made sense to me that the reason that the number of overdoses that I was attending are, or my members were attending, had dropped significantly, was because of Insite.”

But political tension continued. Insite faced major legal battles to secure its place, ones that went all the way to the supreme court. But in 2011 Insite won in a unanimous decision. By that point, there were years of research backing the idea. The court essentially ruled that closing the facility would undermine people’s health and safety, and so eight years after opening, Insite was there to stay, no longer facing a federal legal threat of closure.

Fentanyl’s influence

The opening of Insite was major. But around 2015, when fentanyl and other more powerful synthetics hit the streets, Insite couldn’t hold back the flood.

Fentanyl upped the stakes and changed the game. It’s a potent opioid that delivers a powerful high, and it made its way into the illicit drug supply. In a narrative playing out in cities across North America, seasoned drug users and younger ones alike started overdosing at unprecedented levels.

“There’s all this good stuff happening, there’s great people working, and yet there’s so many people dying,” said MacPherson, who now heads the Canadian Drug Policy Coalition. “It’s like the worst ever.”

By the end of 2016, the death count for all of British Columbia rose to nearly 1000, more than double the overdose peak of the 90s. Then it tripled. Tim Gauthier, head nurse at Insite, recalls the tsunami that hit one day in December 2016: staff responded to more than two dozen overdoses in just one day, compared to its average of two or three.

Insite was basically the only game in town for supervised injection, aside from a much smaller place inside a health center for people for HIV. The regulatory and approval process had made it difficult for additional places to open.

And so while Insite itself was super busy, it was limited. It oversaw just a tiny portion of all the drug use in the neighborhood.

“I’ve lost so many people I care about,” Tina Shaw said.

Shaw says she had a big cocaine addiction for years. When the overdoses started mounting, she wanted to do something, to get involved.

“We weren’t going to stand by and let people keep dying,” she said.

Once again, pain turned to passion.

“That’s when we took it into our own hands,” Shaw said. “We put tents in the alleys.”

Supervised injection outside Insite

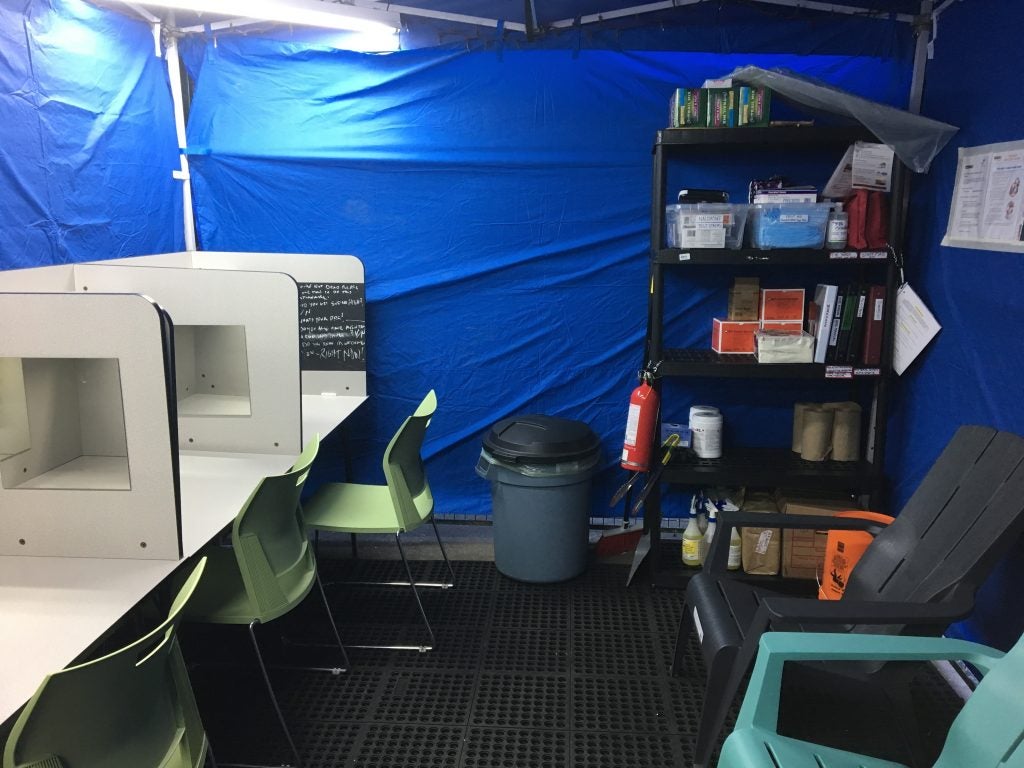

She and other activists, including Ann Livingston, setup medic tents in the thick of where lots of people were overdosing in the Downtown Eastside. They’d volunteer, standing watch over people injecting with their naloxone and breathing masks at the ready.

The tents were illegal, but health officials did not shut them down. Instead leaders visited and decided to fund them, the supplies and the staff.

“Previously people were dying, and so you put a trailer there and all of a sudden people are living and their bodies on not on the ground. So who’s gonna complain about that?” said Mark Lysyshyn, chief medical officer for Vancouver Coastal Health, essentially the county health department that also oversees Insite.

And so some of those the tents got real roofs and moved indoors. Social workers are also either on site or easily available through affiliated non profit agencies.

Shaw is a petite redhead with a large presence. She walks toward the one overdose prevention site she’s been most active in lately, but can’t get from point a to b without stopping someone she knows, or someone stopping her.

“Hey you ok?” she said, poking a man sitting against a wall on the sidewalk. He responds with a yes.

“Just wanted to make sure you weren’t overdosing, sorry to wake you up!”

She arrives at the Molson Overdose Prevention Site. The entrance is in an alley about a block from Insite.

“As crazy as it gets, it’s family,” Shaw said. “It’s kind of like a home.”

But unlike Insite, nurses don’t run this place. Peers do.

“We’re also in active use, most of us, and there’s something there that exists between us, that’s why we’re peers,” said Daniel Beaverstock.

Beaverstock is 42 and originally from a small village in Ontario. He works the check-in counter on a recent afternoon, asking people for a code name and what type of drug they’re using. When a table opens, he directs them to the main room. Like everyone else who staffs the place, he’s trained to respond to overdoses.

Beaverstock has had a lot of close calls himself.

“I said if there’s a way I can give back, just ask and I’ll do it,” he said.

When Beaverstock is not on the clock, he may also inject here. And that’s fine, according to the rules. Peers generally take four hour shifts. The basic rules are do what you need to do to avoid going into withdrawal, typically shooting up every four hours or so. If anyone seems too high to do their job, like they’re nodding off, they get sent home for the day.

The main injection room of the Molson site is wide, with eight rectangular metal tables, spaciously set up along the walls. It’s a lot more low key compared to Insite.

People can share booths, and even help one another inject. The main ‘no no’s’ are no money exchanges, so dealers don’t set up inside; no physical threats or hitting, though no one is ever barred for life; and no uncapped needles, to avoid accidental sticks.

“I’m just going through a really rough time right now,” said Stephanie Peterson, sitting at booth three. She says a dear friend died last night. “If we didn’t come here, there’d be so many more deaths, so many more deaths.”

Peterson lights a match to cook up her drugs.

Colin, another peer who didn’t want to use his full name because of his active use, moves around the room on a clear mission, constantly restocking supplies and cleaning tables when people are done. He says for years his addiction isolated him, making his world small. Then he says this place hired him.

“So I think this job is helping give me more purpose in my life again, so my life’s getting better,” he said.

Nearby, a man injects in his neck. At one point, another person’s pet rat gets loose in the chill out area. It’s a cluster of chairs in the back next to a vending machine. It can at times seem a bit erratic in and around here, with people having good days and bad. Other staff move toward a man in booth seven. He’s older, tall and slender, and known to overdose. A peer supervisor standing nearby says they put an oximeter on his finger. It’s a little device that checks heart rate and oxygen levels.

“If it’s below 90, we like to put a mask on him or give air or remind him to breath,” Kevin Thompson said.

Moments later, Peterson walks over to the man. She puts her arm on his shoulder. They’re mourning a mutual loss.

An explosion of new sites

No one’s ever died in any of these more informal overdose prevention sites, according to Vancouver Coastal Health. The regional health authority basically leveraged a special emergency declaration to greenlight and fund the more informal sites. It doesn’t technically protect people from arrest, but local police are on board.

Bill Spearn, now an inspector with Vancouver police department’s organized crime section, says the department views the sites as a health care service to prevent overdose deaths. It’s not a law enforcement issue, he says.

The federal government has also created an avenue for these overdose prevention sites to apply for an exemption from federal drug laws, and eased the process for formal supervised sites, similar to Insite, to open. One of the more informal sites has since achieved that designation.

“We’re having this emergency, but because these overdose prevention sites are sort of community run and can be implemented quickly, you can establish them exactly where they’re needed,” said Lysyshyn.

Outreach workers are at the ready around these places, to help connect people with addiction services. The sites have taken different forms. One place now has an outdoors space, with a big fan in it where people can smoke drugs.

“We call it the smoking and poking room cause you can smoke and you can poke,” said Jodie, also known as Wheels around here, who’s working the check in.

As of mid June, 46 overdose prevention sites are up and running in British Columbia, according to the Ministry of Mental Health and Addiction. Lots of sites have also moved inside homeless shelters and apartment buildings, where people would otherwise use in their rooms and potentially overdose alone.

There’s an overdose prevention site just for women, and another geared toward First Nations people.

The first site outside the Downtown Eastside in Vancouver opened in May, in a semi outdoor tent next to a main hospital.

Meanwhile, downtown business leaders requested a site to prevent overdoses in the bathrooms and alleyways of their shops.

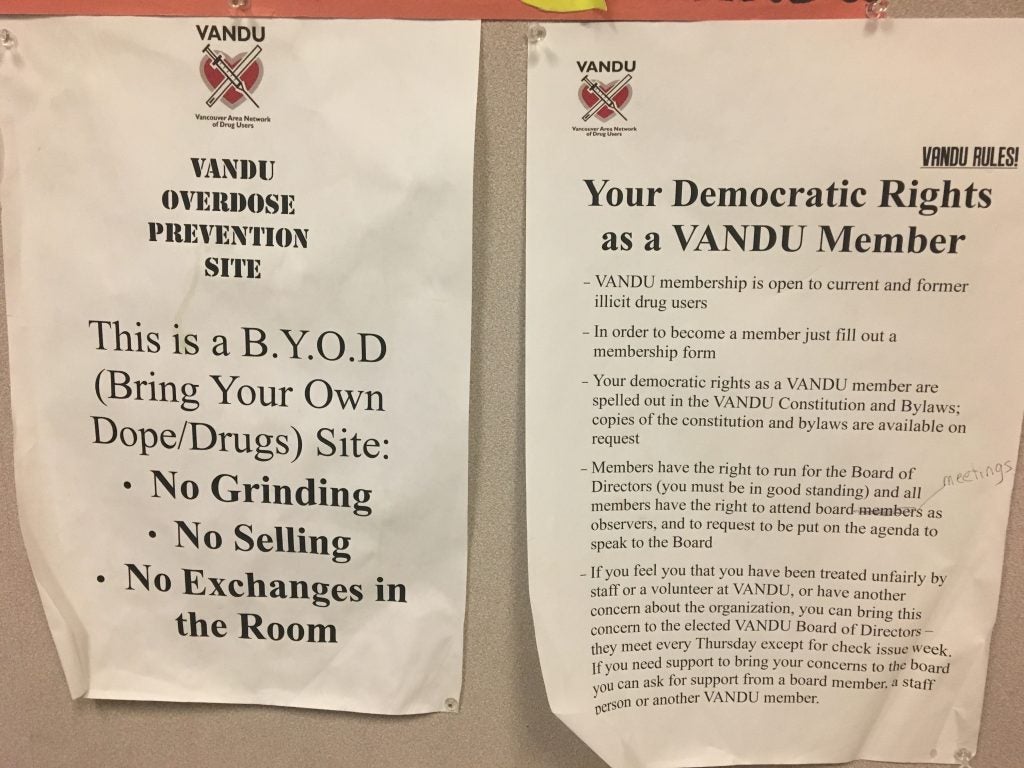

Back on East Hastings street, Trish prefers a smaller site that’s completely run by peers in the back of the Vancouver Area Network of Drug Users’ main headquarters.

She is staying in a tent nearby, and only wants to give her first name because of her active use. She says she has been trying to get a more stable situation and manage her addiction, but it’s difficult. Places like this are lifesavers.

“It means that we get to be safe and that we’re not always alone,” she said. “We don’t have to be alone if we don’t want to be. I’ve been on the street for 10 years, alone.”

She sits at one of the tables, emptying her bag of stuff and taking a good 15 minutes, combining and prepping her drugs.

“So like my whole life I’ve had no one to look up to and no one to stand by my side, and almost everybody in my life that’s hurt me,right? So to have people be the bystander and make sure I don’t die at the end of the day, it shows me that people — even when aren’t obligated to — they still care. Which is the biggest thing for me, i just want somebody to not want me to leave, you know?”

Overdoses continue

Even with these new spaces, people are still dying in the region. This spring an even more potent batch of synthetics made its way into the heroin drug supply. British Columbia experienced one of its worst months yet for illicit overdose deaths,162 in March, according to the Coroners Service.

That has people like Suzanne Ouellette, a longtime Downtown Eastside volunteer and supervisor at the Molson overdose prevention site, on high alert. On a recent walk across the street, she spotted a man overdosing in the alley.

“And he just sort of slumped down to the wall and was in a slouched position and he was purple,” she recounted after stepping back inside Molson.

She and someone else nearby jumped in right away.

“So we got him in a prime position, gave him narcan, inserted an airway and breathed for him.”

It was a complicated resuscitation. They got him back.

“Course he was just coming up when the fire department arrived, which is wonderful.”

Ouellette chokes up a little when she stops to process what happened. It weighs on her.

“Once the adrenaline is over and he’s standing up or sitting up and is able to talk, that big rush is gone,” she said. “And you think about about maybe that one or two minutes we hadn’t gotten there, he wouldn’t be alive.”

Moments later, though, Ouellette’s back to work, managing the site. Her evening wraps up training a new peer at Molson in using the oxygen machine and breathing masks — ready to respond.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.