How video games could help you keep your emotions in check

Scientists are interested in video games as a potential tool to teach players how to get a handle on their emotions.

Listen 8:58

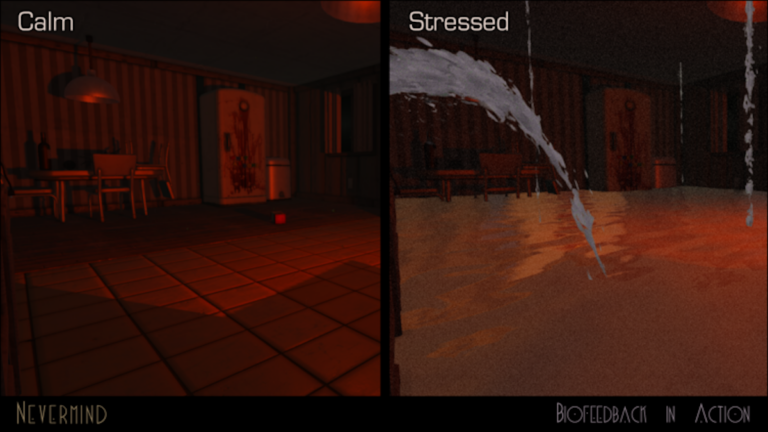

Nevermind is a biofeedback-enhanced thriller video game that that teaches players to control their emotions.

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

Around 10 years ago, video game designer and horror fan Erin Reynolds made a game called Nevermind while in graduate school: You play as a psychologist of the future, delving into the memories of people who have experienced a deeply traumatic, haunting event.

The twist? The patients cannot remember the traumatic events, so the player must figure it out by navigating their minds.

You do this by solving puzzles in increasingly creepy and disturbing environments: a dark forest where baby doll heads fall from the sky, or a circular room made up entirely of human faces that stare at you with huge, gaping mouths.

Nevermind is one of the few games you can play with a heart rate monitor — if you get scared, stressed, or anxious, the game will measure your response and become more difficult.

So, the player has to stay calm and control their emotional response to what’s happening.

In a roundabout way, Reynolds realized that this could help players deal with their stress or anxiety, just as the game Dance Dance Revolution had tricked her into exercising.

“I like to call it a stress management tool disguised as a video game,” Reynolds said. “I’ve gotten many emails from people who played the game and reached out to say that they’ve recognized themselves in some of the characters, and they’re going back to therapy. Some of them say that they feel like they’re being seen, because trauma’s being represented in a way that they can relate to.”

She made the game for entertainment, not as a form of therapy. But scientists are interested in the potential for treatments that use the underlying principle — a game could respond to how a player is feeling, and, in turn, teach the player to get a handle on their emotions.

Behavioral scientist Joanneke Weerdmeester loves video games and admires Nevermind.

For her PhD in psychology, she studied DEEP, a game that started as an art installation and feels like a virtual reality jellyfish simulator. As a player, you wear a virtual reality headset and submerge in an underwater fantasy world with fish and calming music.

But you don’t move with a controller or keyboard; you move by wearing a belt around your diaphragm, which measures your breathing. Deep calming breaths move you forward; short narrow breaths leave you stranded.

Weerdmeester wanted to know if this game could actually help people feel less anxious by teaching them how to take deep, calming breaths through their diaphragm. She divided research participants into two groups: One group played DEEP, while the other learned breathing techniques using a guided breathing app. Both helped people with anxiety, but the game had an extra benefit:

“Only players that played DEEP showed an increase in this feeling of self-efficacy, so this feeling … that they were competent enough, and it also showed an increase in their perceived ability to cope with stressful situations,” Weerdmeester said.

One key difference between the game and a mediation app is that the game shows a player when they have mastered a skill, which leads to self-efficacy.

Weerdmeester is still working with the development team on this and other games. But doctors at Boston Children’s Hospital already use games to teach emotional control.

Psychiatrist Joseph Gonzalez Heydrich treats children with severe anger problems. He thought he could use video games to teach anger control techniques, like deep breathing, in a more engaging way for children — which would also mean he could rely less on prescribing medications.

Subscribe to The Pulse

He asked his research assistant, who is good at programming, to make something like Space Invaders, a game in which the player has to shoot asteroids and avoid friendly ships. But they added a twist: The player measures their heart rate with a wrist band while playing. If their heart rate goes up, their ship will only shoot blanks.

“The kids really picked up on this very quickly, we thought that it was going to take a long time to remodel the brain … they were very quickly lowering their heart rate in the game to be able to score points,” he said.

Their team did a few trials with young patients, between the ages of 10 and 17, who played the game for a few minutes for several rounds. One trial included patients in an inpatient psychiatric unit who had more serious problems.

The researchers found the game did help the children control their anger — and the benefits seemed to carry over into other situations, beyond the game. Now they are running a more extensive trial with 200 patients.

So, where could the use of video games in managing emotions go?

Kelli Dunlap is a clinical psychologist, a game designer, and a parent. She has tried some of these games with young children, and she says they can be successful in helping them to regulate their emotions.

“It’s really, really cool to see someone playing a game, and all of a sudden, they’re noticing their screen is getting red, or it’s getting harder to play, and like, ‘Oh that’s right, I need to check in with myself. I need to remind myself to calm down.’ That’s such a difficult thing to teach.”

But, she says, there are a few problems with any game designed to help people with their mental health:

First, even though these games can be more fun than therapy, it is still hard to get a child to spend the amount of time with the game that they would need to get the full benefit.

“It’s cool and novel for about a day or two, but because the games they use are … small mobile games, most of the time kids get bored with them and then walk away,” Dunlap said. “Even if we can get attention, it is hard to maintain attention and engagement, because what we’re asking them to do is practice skills that we want them to practice, but it’s not always the most fun or playful way.”

Another issue: The equipment is expensive, and not everyone can afford virtual reality headsets.

“For the type of patient who would benefit from these interventions and has actual access to these interventions, I think they can be very effective,” Dunlap said. “However, it is a small slice — better than nothing, but they’re also not going to disrupt or upturn the current struggle around mental health and getting access to mental health resources.”

She hopes the technology and the games will improve because it is another way to help people address their mental health. It’s a new way to personalize games and make them unique to the player, which could also make video games — in general — more interesting.

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.