Hope, devastation, and finally, a treatment: One family’s road to gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy

A family in Wilmington, Delaware, faced a looming deadline to get their son a new gene therapy treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Listen 8:27

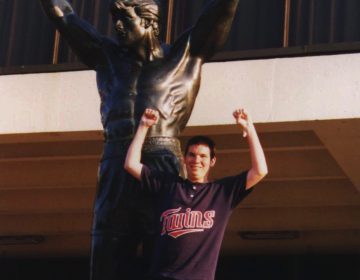

The Huber family (from left), Cash, Jena, Stone, and Phil, and big sister Ava (not pictured) at home in Wilmington. (Emma Lee/WHYY)

This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast.

Find it on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever you get your podcasts.

A tiny, fluffy dog named Pepper yipped at the activity going on around her as a 5-year-old boy zoomed in and out of the kitchen at the Huber home on a recent Wednesday night.

“My name is Stone!” he shrieked before jetting off into the next room.

His 6-year-old brother, Cash, came around the corner quietly and gave a shy wave. He was a little irritable from a recent round of steroid treatments, but perked up as he showed off a toy car with lights.

Their mother, Jena Huber, was making a snack out of some crackers, honey, and cheese. She just returned home from work as a dental hygienist. Her husband, Phil Huber, came in from the backyard where the boys were playing and let in Dingo, a larger rescue mix, who added some barks to the party.

“This is the normal,” Phil said with a laugh.

Things have recently settled down at the Huber home in Wilmington, Delaware, after a few “emotionally draining, exhausting” weeks of dealing with medical care for Cash’s Duchenne muscular dystrophy, a rare disease that causes the body muscles to deteriorate over time.

About 20,000 children globally are diagnosed with this incurable genetic disorder every year. The disease is always fatal, and most people who have it don’t live past their 20s or 30s after suffering heart and/or respiratory failure.

There are few treatments available, and they primarily help manage the symptoms and toll of the disease. Until this summer, gene therapies that could modify the underlying genetic problem to create a longer lasting treatment option had mainly existed in various stages of clinical trials.

But the Hubers were always closely watching.

“It was the golden goose from day one,” Phil said. “My eye was on that prize from day one.”

‘We were kind of left hopeless’

Before Cash’s second birthday, Jena and Phil noticed their son was showing signs of muscle weakness.

It’s an early indicator of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Other symptoms can include difficulty standing, enlarged calves, fatigue, and frequent falls.

The average age of diagnosis for this disease is about 5 years old. But in younger infants and toddlers, an early warning sign can be mistaken for a common motor delay in child development.

In Cash’s case, the Hubers were insistent on more testing. They eventually got the devastating news that their son had this inherited neuromuscular disorder.

“We were served the diagnosis, and I say served, because it was like, ‘Here’s your death sentence and good luck,’” Jena said.

Subscribe to The Pulse

As horrible as that moment was, Jena said she and Phil didn’t wallow too long in the diagnosis. They immediately started researching future therapies that might one day be available to Cash.

They learned about gene therapies that were being tested to slow the progression of the disease, pause the breakdown of muscles, and ultimately extend the lifespan of these children.

“‘There might be in the future this kind of treatment, they’re working on it,” Jena said doctors told her. “‘But it’s in clinical trials and it’s not necessarily going to be available to you.’”

Clinical trials targeted boys as young as 4, because at earlier ages, many kids with Duchenne muscular dystrophy can still walk and are not yet using wheelchairs.

Jena and Phil said they saw a potentially life-changing opportunity for Cash, and moved to get him in a clinical trial for gene therapy when he was 4 at a hospital site in Virginia.

He passed all the preliminary medical tests and screenings, and while Cash was still very much ambulatory, he didn’t complete a test where he had to go from laying down to standing up in under five seconds. So, he was disqualified.

Any excitement that the Hubers had once felt vanished.

“It was a behavioral thing. He just didn’t want to do it,” Jena said. “So, he failed out of that and we were left kind of hopeless again, because there was no timeline on when this would be FDA approved or commercially available for him.”

‘We don’t have that kind of money’

After years of clinical trials, drug manufacturer Sarepta Therapeutics won accelerated approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for ELEVIDYS in June.

It’s the first approved gene therapy for Duchenne muscular dystrophy, given as a one-time infusion. The FDA has required Sarepta to complete a follow-up clinical study to confirm the drug’s clinical benefit.

The treatment doesn’t restore muscle cells that have already been lost, but researchers said it shows promise in preserving and improving muscle strength. As for how long, nobody knows yet, but for the Huber family, this was the lifeline they had been waiting for.

The treatment is narrowly approved for children 4-to-5 years old who can still walk. That meant a race against the clock for Cash as his 6th birthday was fast approaching in July. His parents rushed him to Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, where the treatment was being administered.

And then they learned that the upcoming birthday was just one obstacle.

“They sat me back and they’re like, ‘So yeah, this is going to be $3.2 million,’” Phil said. “I remember just sitting back in my seat and like my whole heart, I was like, I’m sorry you guys, but we don’t have that kind of money. And they’re like, ‘No, no, no, the insurance will pay for it.’ Well in my mind, I was like, the insurance is going to pay for this, $3.2 million?”

Phil had good reason to be skeptical, especially considering what happened next when they submitted the request to their Delaware-based health insurance company.

“The first one was denied. [We appealed] immediately,” Phil said. “They have 72 hours, then we put the other one there – denied.”

For weeks, Phil spent hours on the phone every day – with the insurers, with activist organizations, with anyone who might be able to help as he desperately searched for a way to get the treatment approved and paid for.

Meanwhile, Cash turned 6 on July 17.

Jena said she got through the stressful and frantic time on auto-pilot most days, filled in between with sleepless nights. Devastation began to set in as she feared that they might miss out on the therapy for Cash after coming so close.

“Because this was something we went through just a year and a half ago,” Jena said. “We failed out of the trial, and then it was like dangling a carrot and the rug was just taken out from our feet again.”

After several appeals and a petition letter signed by thousands of community members and families, the Delaware insurance company reversed its decision and approved coverage in August.

Because Cash had completed and passed all the physical and medical requirements at CHOP before turning 6, he still qualified. Cash received the one-time gene therapy infusion in early September.

“It was such a relief, because we got him there, he was healthy, we quarantined him, he wasn’t sick,” Phil said. “We got him in there in his little bubble of life and we got it in him, and he was so good. He’s just such a good kid.”

The Hubers said they’re already seeing changes in Cash.

“To see him run around with his brother, wrestle when he wasn’t wrestling a few weeks ago, he’s bounding up the stairs — he wasn’t doing that before,” Jena said. “I’ve been giving him piggyback rides up for like six months now. It’s been really exciting.”

‘Cash is going to grow up’

Jena and Phil are under no illusion that this treatment is a cure. They know it’s still being studied, and there’s no clear roadmap for what trajectory Cash’s disease will take now.

But they’re hopeful this will buy them more time with their son.

“He’s still not going to be able to run like a dash the way that kids do, and climb things,” Jena said. “But he can at least walk out to the playground and walk around and be included and catch up and keep up in his own way, and that is just a dream come true for us.”

For Phil, the dream for Cash is a simple one.

“I just want him to be able to walk for the rest of his life. That’s it,” he said. “He doesn’t have to be a superstar. He can just be our superstar. All our expectations as a parent are just out the door, because now it’s just like, the kid’s just got something amazing and he’s just going to live the best life that he can live at this point, and he’s going to take advantage of every moment.”

As exciting as this moment is, Jena and Phil said they feel heartbroken for so many other families with children who are older than 5, for whom this drug is not currently approved for treatment.

“They’re still walking, they deserve this drug,” Jena said. “Their hearts are stable, their lungs are functioning fully. They deserve it just as much as Cash does.”

Leaders at Sarepta Therapeutics said in an October statement that they intend to seek broader FDA approval to use the therapy in older children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

Cash started kindergarten this fall, where he’s learning the alphabet, making new friends, and playing outside at recess.

He continues to get weekly bloodwork and his parents take him to the hospital about once a month for checkups following the gene therapy. Researchers will likely study cases like his for the rest of his life.

Jena and Phil said they can’t help but imagine what that might look like for Cash, even if it isn’t a certainty.

“Cash is going to grow up and he’s going to be an adult. He’s going to be a 40, 50, 60-year old man. Before, that wasn’t something we would have been confident in saying. I probably would have said it anyway, but I don’t know if I would have believed it,” Jena said. “And now, it’s something that’s going to happen. So, I don’t care if they take blood from him until he’s 60. He’s going to agree to it, too, because he’s going to understand, which is going to be a beautiful thing.”

WHYY is your source for fact-based, in-depth journalism and information. As a nonprofit organization, we rely on financial support from readers like you. Please give today.